AdLib Functions

Many players have experienced the music output of the game through a Sound Blaster or other compatible expansion card, but some might not be aware that the programming interface for music playback was originally introduced by a product called the AdLib Music Synthesizer Card in 1987. By most accounts, the AdLib was the first mainstream sound card available for the IBM PC platform. Although the AdLib is capable of producing rich audio that puts the PC speaker to shame, it was only designed to produce music and music-like output; there is no hardware to handle arbitrary waveforms for sound effects. Within a year or two, Creative Labs introduced their competing product, the Sound Blaster, which boasted perfect compatibility with the AdLib’s programming interface. It also included analog waveform recording/playback and an integrated game port – at a very attractive price – making it an absolute smash hit with the gaming public. AdLib (both the product and the company that created it) soon faded away, but its interface lived on for years.

The AdLib card is really nothing more than a bundle of off-the-shelf components stitched together to function with the PC’s bus interface. At the heart of the unit is a Yamaha YM3812 music synthesis chip, which Yamaha called the FM Operator Type-LⅡ or OPL2. The AdLib’s interface is exactly the same as the OPL2’s, and any programming techniques that work on the OPL2 will work on the AdLib (or any AdLib compatible hardware) with suitable I/O address translation.

Making Waves

In order to understand what the OPL2 chip does and what causes its characteristic sound, it’s necessary to get a bit into the weeds and explore the math behind sound and music. The building blocks of synthesis are simple – the same output could be produced on a graphing calculator with little effort – but artful tuning of the input parameters produces effects that are pleasing to the ear.

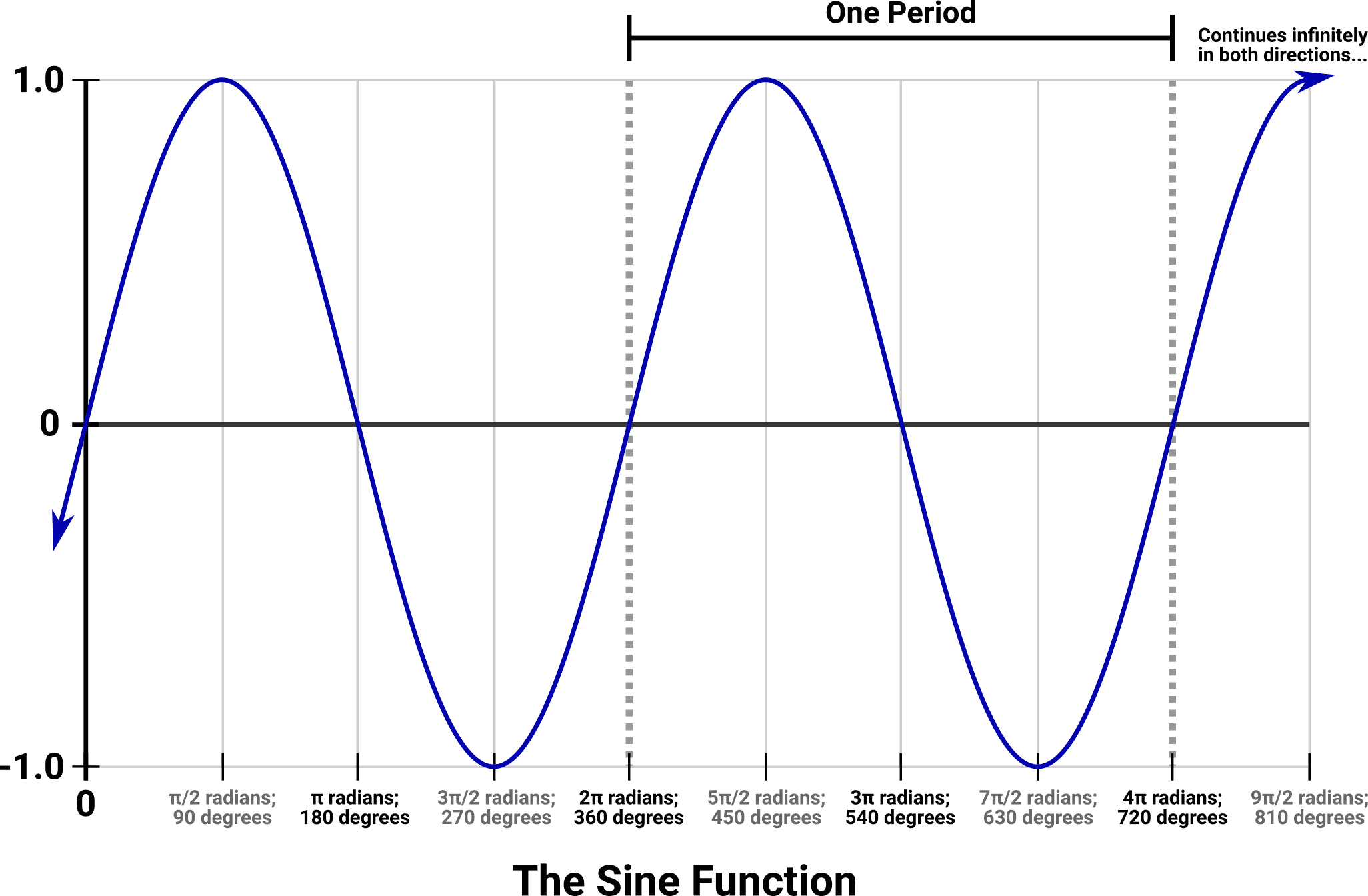

All output of the OPL2 is built from a single building block: the sine function. Given a series of increasing input values, the output of the sine function starts at zero, drifts up to 1, changes direction and goes all the way down to -1, and then returns back to zero. This cycle repeats infinitely at regular intervals, producing a smooth and stable output wave with many useful properties and symmetries. The repetition behavior depends on the unit of measurement, but typically one period of the wave fits into 360 degrees or 2π radians of input:

Round and Round

The sine function can be described (albeit a bit imprecisely) by the following physical process:

Go out into a field or other open space, and draw a large circle on the ground. Draw a straight line that splits the circle exactly in half. Stand at the edge of the circle, and start walking around its perimeter. At regular intervals, measure how far you are from the closest point you can reach on the dividing line. Your position along the outside of the circle is the X axis of this chart, your distance from the dividing line at each point is proportional to the Y value, and the Y value’s sign indicates which side of the dividing line you are standing on.

Eventually the measurements repeat, because you are walking in circles. Try not to do it for too long or the neighbors will start to wonder if you’re okay.

This is interesting to look at and all, but some concrete connections must be made to produce audible output. In audio synthesis, the input to the sine function is derived from the passage of time. A counter value tracks the cumulative number of clock “ticks” that have occurred since a fixed point in time, which produces a value that increments at a linear rate. Feeding this counter value into the sine function causes the output to repeat (oscillate) at a constant and predicable rate. The function’s output is connected to an electrical circuit that causes a speaker to physically move in lock-step with the sine wave as it cycles between -1 and 1. This vibration excites the air molecules in the surrounding area, which can be detected by structures in our ears as sound.

Basic Sine Wave, Middle C (Download MP3, AAC, or WAV.)

Most would call this a beep, which is not very interesting by itself, but it sets the stage for manipulation of the input and output parameters to explore the capabilities of this fundamental arrangement.

Frequency and Pitch

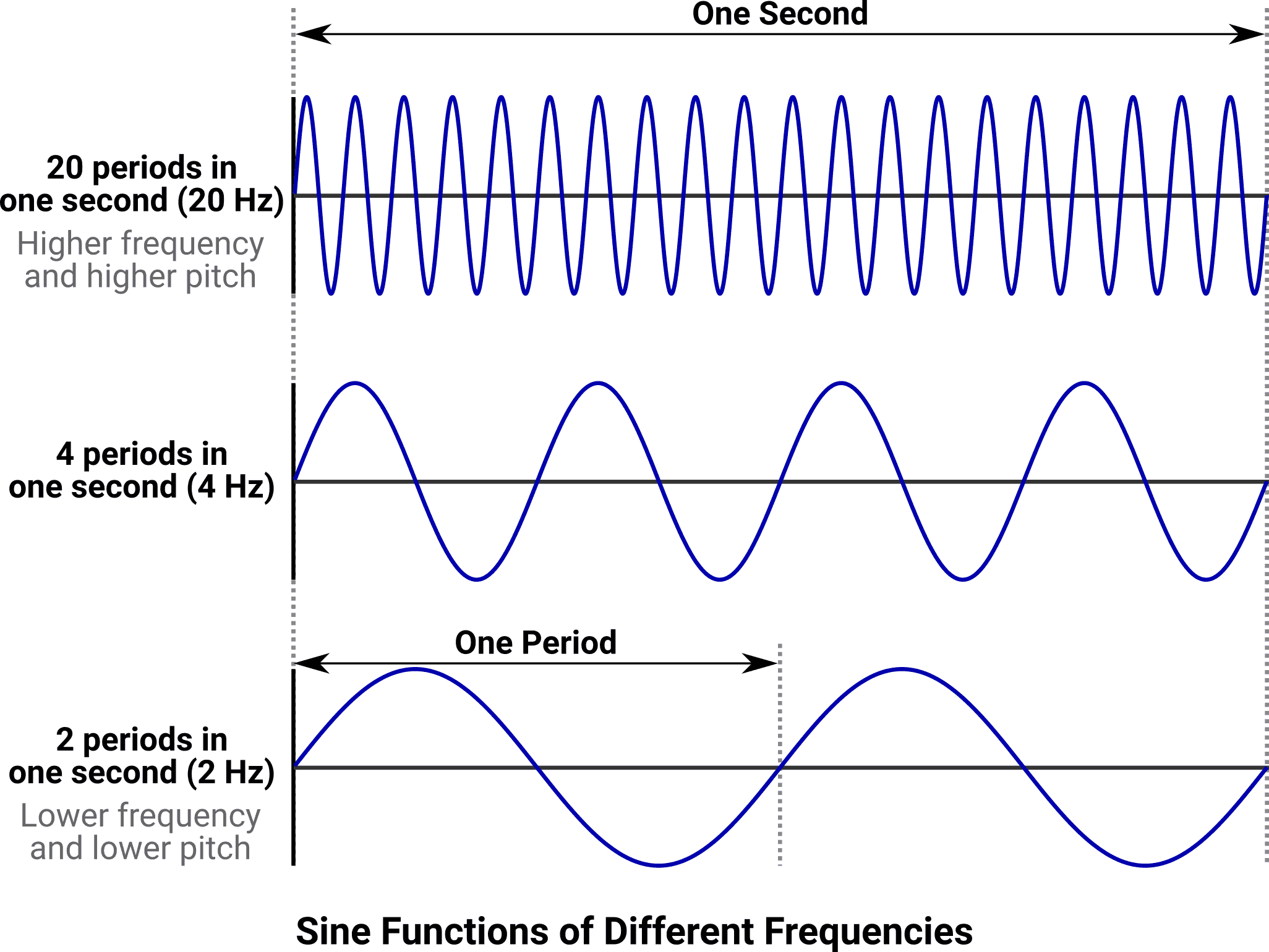

In our abstract example, we glossed over the relationship between the passage of time and the repetition rate of the sine wave. But this is actually the most important relationship in terms of controlling the output. This rate is measured in hertz (Hz), which is the number of periods of wave repetition that occur in one second. This is ultimately governed by the rate of the system’s clock ticks, which is constant, being divided by a frequency control value. This allows the repetition rate to be reduced, producing a lower pitch, or increased to produce a higher pitch:

The graphed frequencies are excessively low for the benefit of visual clarity – the lowest frequency value that humans perceive as a tone (or note) is around 20 Hz. Below that, we sense rumbling, vibration, clicking, or rhythms. As frequencies increase, tones become whistles, then irritating/painful squeals, followed by hisses, then silence above about 15,000 or 20,000 Hz, depending on the age of the listener and the health of their ears. Musical frequencies are generally in the range of about 25 Hz (e.g. a contrabassoon) to 5,000 Hz (a piccolo), although practically all instruments produce additional frequencies outside of this range which add richness and complexity to their sound.

By taking the basic sine wave and altering its frequency, we get something like the following:

Discrete Sine Frequencies (Download MP3, AAC, or WAV.)

Most casual listeners would still call this a beep, but by carefully manipulating the frequency value we are able to divide the constant clock rate into something distinctly musical. This example uses abrupt and discontinuous jumps in frequency, but it is also possible to smoothly “ramp” from one frequency to another over time:

Continuously Variable Sine Frequencies (Download MP3, AAC, or WAV.)

This example uses fine changes in frequency, recomputed at each output point, to create a pitch bend (or portamento) over time instead of abrupt jumps between tones. Both techniques are appropriate for music synthesis, depending on the context and desired aesthetic.

Amplitude and Loudness

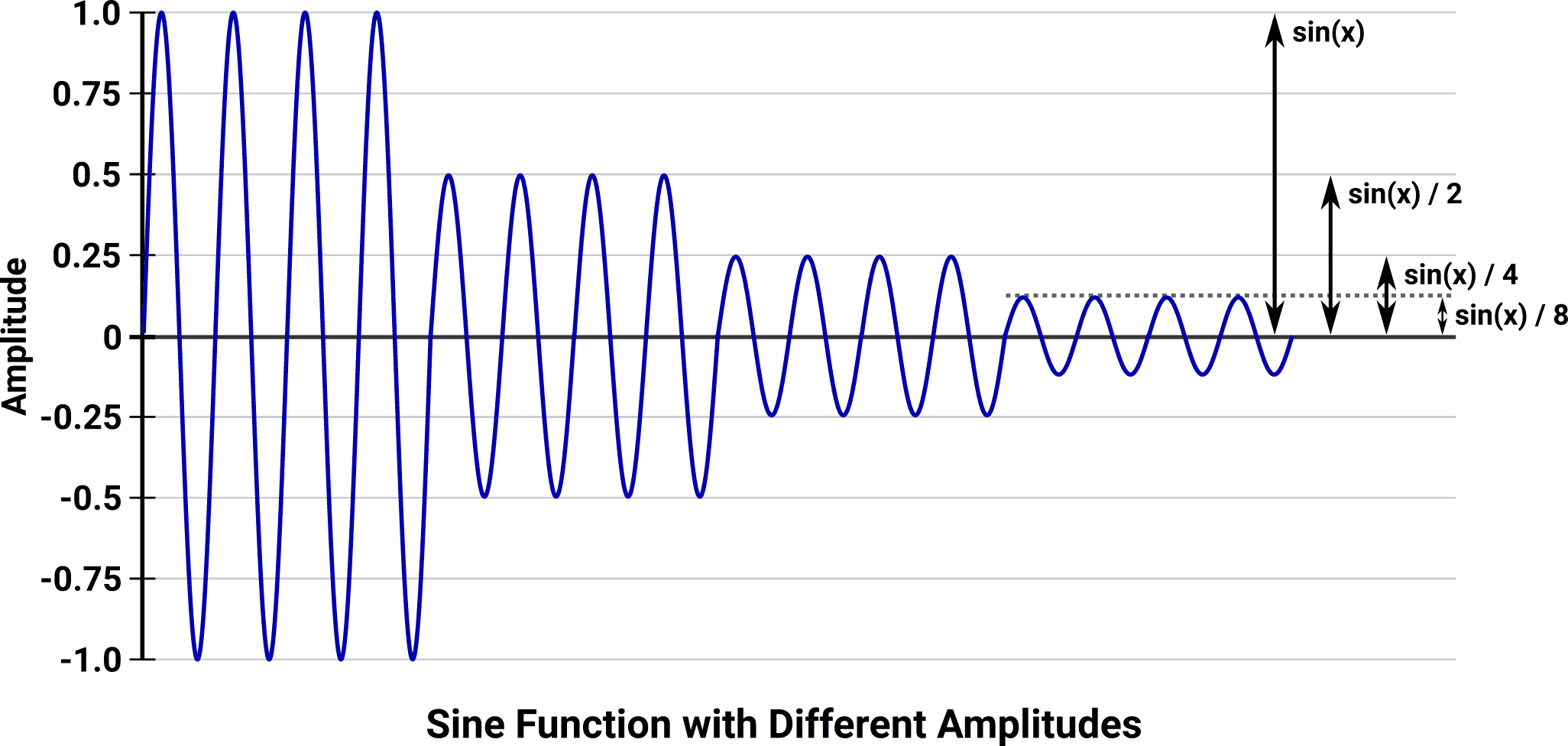

In all of the previous examples, the output of the sine function stays within its original range of -1 to 1. This range of values is mapped to the absolute minimum and maximum movement range of the speaker, limited by its physical construction and the available supply of electrical power. Since it is not possible to make the output any louder, the only other remaining dimension of control we have is to make it quieter. By dividing the output of the sine function by a constant amplitude scaling factor, we are able to reduce the amount of travel the speaker takes, thus reducing the perceived loudness of the output. When graphed, it looks something like this:

As an audible example, it sounds like this:

Rhythms from Varying Amplitudes (Download MP3, AAC, or WAV.)

This example is a sine wave of constant (and otherwise irrelevant) frequency, scaled by a few different amplitude values. The spans of silence are produced by scaling the output to such a minuscule value that the speaker doesn’t receive enough power to move in any direction.

Much like frequency, the amplitude can change over time to produce interesting entrances and exits of individual notes, as well as producing emotional expression over longer fragments of the music.

Thus Beeped Zarathustra (Download MP3, AAC, or WAV.)

Phase

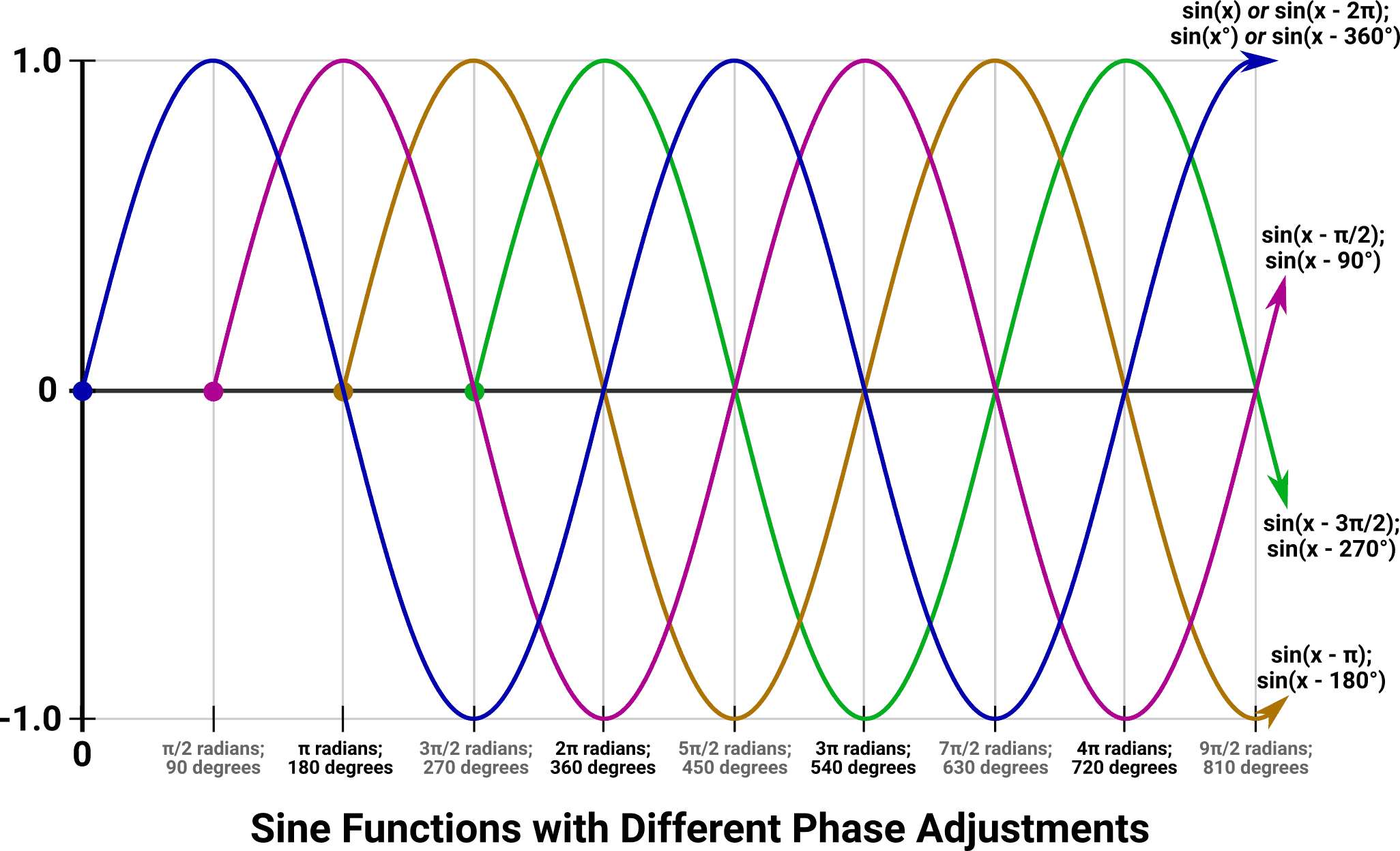

There is yet another parameter available to control the output of a sine wave function: phase. Compared to frequency, which is a measure of the number of repetitions of the wave in a given span of time, the phase value defines exactly where the starting point of that function was, and at which points in time all subsequent repetitions will occur. Phase can be thought of as adjusting the position of the sine wave in time, without changing the frequency it oscillates at.

With a pure sine function, phase adjustments can vary from -360 degrees (-2π radians) to 360 degrees (2π radians) – this can also be thought of as an adjustment of ±1 period. Outside of that range, the result repeats as if smaller values had been used. Positive phase adjustments move the graph to the left, making the signal occur earlier in time, and negative adjustments are the opposite.

A few interesting properties exist: Adding or subtracting 180 degrees (or π radians) perfectly negates the output of the function, flipping the wave upside-down compared to its unmodified version. Adding 90 degrees (π radians) or subtracting 270 degrees (3π ⁄ 2 radians) turns the sine function into a cosine function.

For a single waveform, phase is entirely inaudible – it is impossible for the human ear to detect the absolute position of an oscillating signal in time. When multiple signals are combined together, however, phase plays a significant role in determining how the individual waves interact to produce a cumulative output.

Vibrato and Tremolo

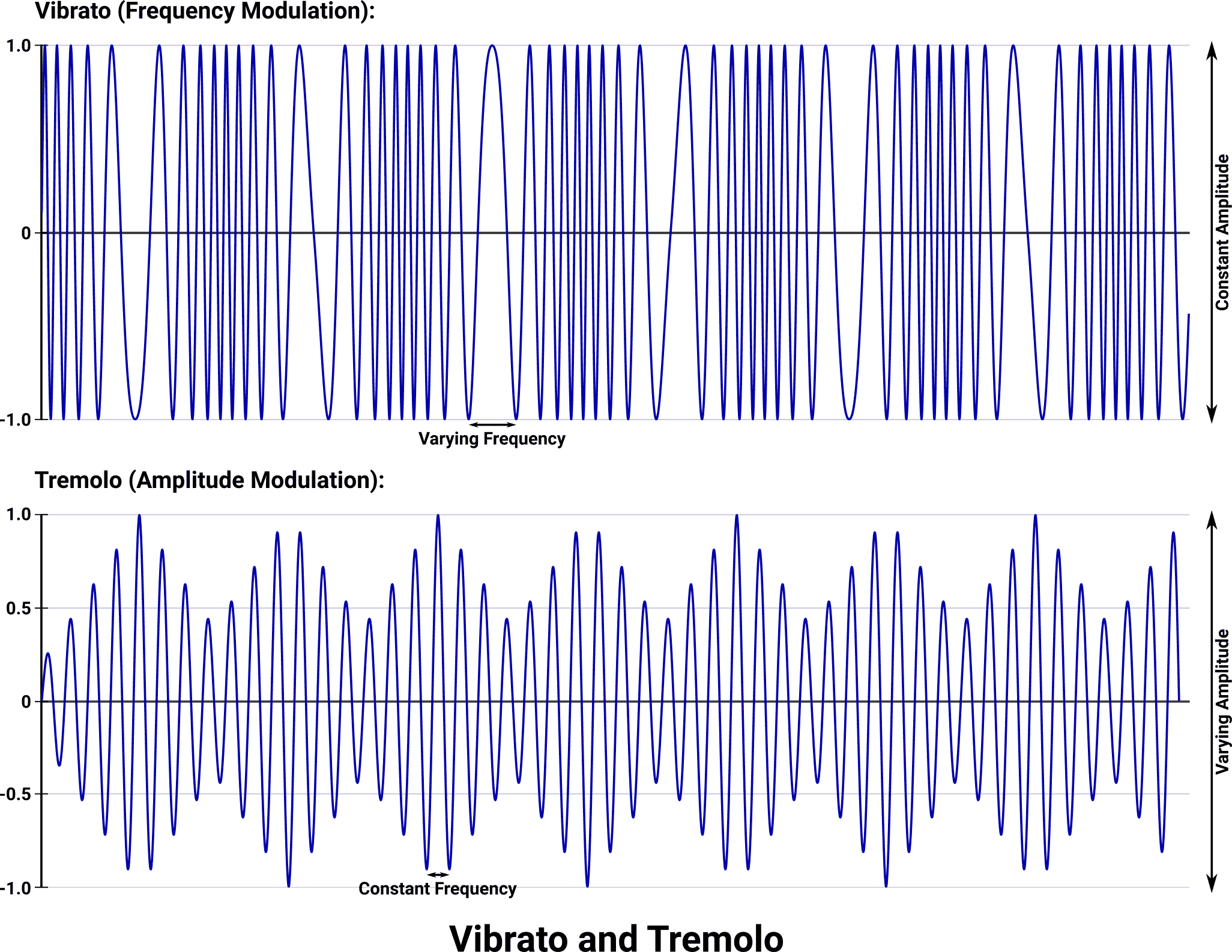

The musical terms vibrato and tremolo refer to variations in frequency and amplitude, respectively, of a tone over time. By slightly adjusting the frequency and/or amplitude of an otherwise constant tone, different effects and emotions can be conveyed.

For vibrato, the base frequency of the sine wave is adjusted by a small and ever-changing amount, producing a sort of “quiver” in pitch over time. The added value varies continuously, sometimes positive and sometimes negative, but it is always centered around zero which keeps the output frequency anchored to its unmodified value. To be perceived as a true vibrato, the rate must be considerably slower than the frequency of the tone – typical vibrato speeds are between 1 and 10 Hz.

Vibrato: Constant Amplitude with Varying Frequency (Download MP3, AAC, or WAV.)

This example uses the same vibrato rate that the OPL2 chip uses: 6.07 Hz.

Tremolo functions similarly, except the scaling occurs at the output side of the sine wave, changing amplitude and producing more of a “flutter” in loudness. As implemented in the OPL2, tremolo can only reduce the amplitude, so it has the net effect of making the overall loudness of a passage somewhat quieter. As with vibrato, the tremolo rate must be much slower than the frequency of the tone in order to be perceived as a true tremolo.

Tremolo: Constant Frequency with Varying Amplitude (Download MP3, AAC, or WAV.)

This example also demonstrates the OPL2 tremolo rate: 3.70 Hz.

These are both actually special cases of more general signal manipulations. Vibrato is a form of frequency modulation (FM) and tremolo is a form of amplitude modulation (AM). FM is of particular importance in creating the characteristic sound of the OPL2.

Frequency Modulation

The most common method of producing sound on the OPL2 chip is through FM synthesis. This requires the use of two discrete oscillators: the modulator which is located first in the signal chain, followed by the carrier that ultimately creates the audible signal. The output amplitude of the modulator is used to modify the phase of the carrier.

A constant phase shift would simply move the peaks and valleys of the carrier’s output wave earlier or later in time, without affecting the way it sounds. A variable phase shift over time, however, creates the effect of the pitch raising or lowering (like in the earlier example of vibrato) without the carrier’s frequency value changing. There can even be discontinuous phase shifts, causing the output to jump wildly to produce noise or other outputs that no longer look or behave like sine waves.

FM is notoriously difficult to reason about because of the interactions between these two oscillators. The modulator’s frequency and amplitude can have a profound effect on the carrier, at times even completely masking the frequency the carrier is tuned to. Fortunately, most frequency combinations sound either non-musical or downright awful, so the OPL2 restricts the composer from choosing all but a few frequency ratios.

In the OPL2, the modulator and carrier frequencies are both locked to the frequency of the note being played and cannot be arbitrarily tuned. The only frequency control available is a multiplier in the range of 0.5x to 15x, which can be applied to the modulator and/or carrier frequencies independently. This allows for a few dozen frequency ratios to be produced while eliminating combinations that are not musically useful.

There is far more control available in the output amplitude of the modulator. This can be at full loudness (in which case the carrier’s phase could be shifted by as much as ±8π) all the way down to silence (where the carrier’s phase would be unaffected).

Since one period of the modulator’s sine function has the capability to phase-shift the carrier by up to four periods in either direction, it’s possible to create a variety of different outputs. The effect of modulation adds harmonics or overtones to the base frequency of the carrier, which are additional frequencies that appear at regular intervals above or below the carrier frequency. The frequency of the modulator determines the spacing of these harmonics (higher modulation frequencies produce harmonics that are spaced farther apart) and the amplitude of the modulator controls how many harmonics are produced.

Using the available controls, the range of modulator settings sounds like the following example. You might want to turn down your volume as a precaution; this is not exactly easy listening.

Middle C Carrier, 0.5x to 15x Ascending Modulator (Download MP3, AAC, or WAV.)

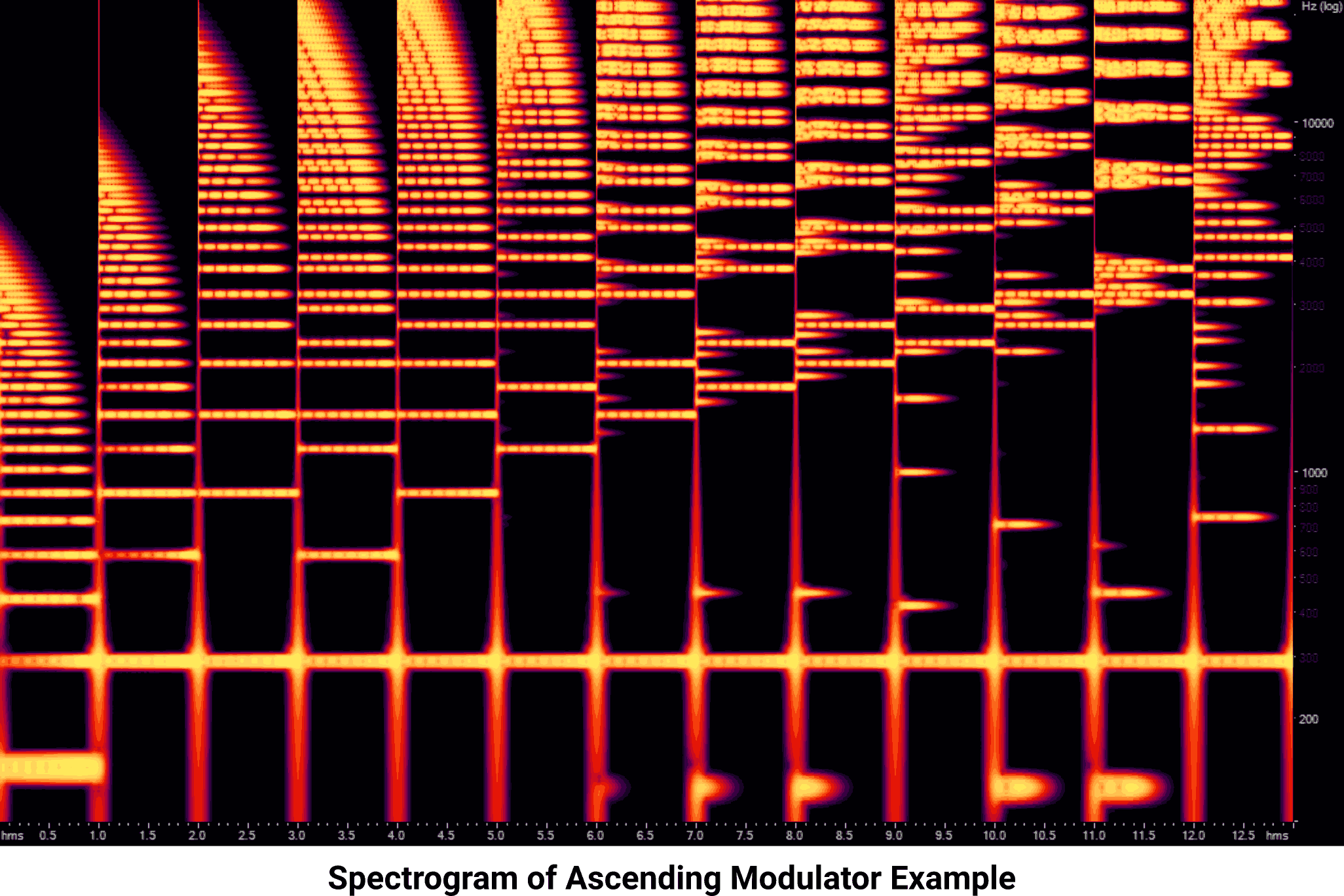

Throughout the example, the carrier is playing a constant frequency and amplitude. The modulator steps through all of its available multiplication settings, from 0.5x to 15x, one per second. Within each multiplication setting, the modulator amplitude begins at full output and decays linearly to zero before switching to the next multiplication setting.

It’s helpful to look at a spectrogram of what this audio looks like. The horizontal axis represents time, the vertical axis is frequency, and the intensity of the colors within the plot represents the amplitude of each frequency at that point in time:

At lower multiplication levels, the harmonics are spaced evenly and decay from highest to lowest. Starting at 3.0 seconds, the harmonics begin to “reflect” on top of themselves on the frequency axis, appearing at more and more uneven intervals and decaying in less-than-simple to predict ways. Across the entire example, the fundamental middle C note at 262 Hz remains in place.

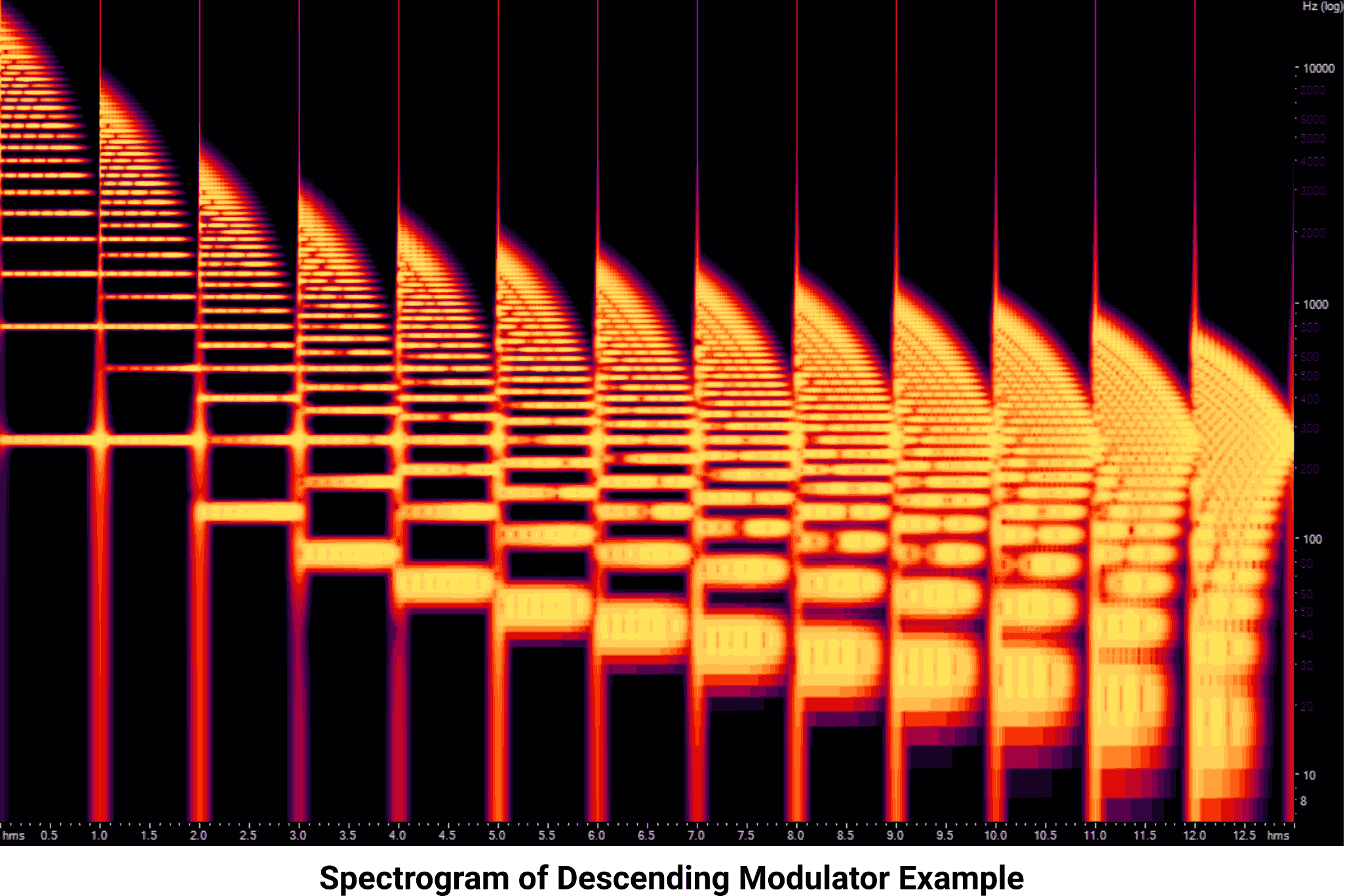

It’s far less interesting to multiply the carrier frequency in isolation. However, a useful effect can be produced by artificially requesting a note to be played at a fraction of the intended frequency (which makes both the modulator and the carrier run at a lower frequency than intended) then setting the carrier’s multiplication to bring the note frequency back to what was originally desired. This has the effect of running the modulator as if it were divided by the carrier’s multiplication factor, which can produce some interesting effects:

Middle C Carrier, 2x to 1/15x Descending Modulator (Download MP3, AAC, or WAV.)

And the spectrogram:

The rest of the parameters are the same as the previous example, and the behavior is the same from a mathematical standpoint. The harmonics become more densely packed as the ratios progress, resulting in lower and eventually sub-audible frequencies being produced. None of the generated harmonics reach a high enough frequency to cause the reflection behavior seen earlier, so the spacing remains consistent and the output is more musical. What’s more interesting is the fact that, although the fundamental middle C note never disappears, it becomes so deeply buried in a sea of harmonics that the output stops sounding like middle C.

Our examples always left one of the two oscillators at 1x, but it’s possible to use any desired multiplier combination between the modulator and the carrier. While it’s true that the available options preclude choosing a ratio which is an irrational number – which substantially limits the range of options – there are still close to 80 ratios available for use. It’s entirely up to the composer to decide which modulator settings work best for a given piece of music. If you’re interested in the world of inharmonic ratios, look up a piece called Stria by John Chowning, the creator of digital FM synthesis.

A few general rules of thumb can be summarized:

- The higher the modulator frequency (relative to the carrier), the larger the frequency spacing between harmonics.

- There is limited space available in the frequency spectrum. Once harmonics reach the end of the available space, they start repeating at irregular spacing elsewhere in the spectrum.

- The higher the modulator amplitude, the more harmonics appear. Reducing the amplitude causes the highest-order harmonics to disappear first. If these harmonics have been reflected elsewhere in the frequency spectrum, they may not be the highest frequency components in the sound.

Beyond that, it’s all subjective. Low modulator ratios produce harmonics that are strictly multiples of the fundamental carrier frequency, which most listeners would describe as having a “musical” quality. Once the harmonics start appearing at non-multiples of the fundamental frequency, the output takes on a distinctly metallic sound – this could be described as “bells” or “clanging” noise. Adding and removing harmonics over time is perceived as a sort of “wow” sound.

Feedback

Some of the oscillators in the OPL2 are capable of feedback, where some fraction of an oscillator’s output amplitude is fed back into its input as a phase shift. This works the same as modulation, but has a distinctly more chaotic result. The amount of phase shift is adjustable from zero to ±4π at maximum. The OPL2 uses a mixture of the previous two output values when calculating the feedback amount for the next value.

Feedback Depth Examples (Download MP3, AAC, or WAV.)

This example steps through the feedback levels from zero to 4π, playing a note that decays in amplitude once per second. At moderate levels of feedback, the sine wave becomes lopsided like a sawtooth wave – rising fast and falling slowly – which adds both sharpness and brightness due to the many harmonics created. As the feedback level is set higher, louder outputs produce more random results, and at extreme levels the sound becomes distinctly percussive.

Note:

The noise produced through this technique is almost perfect white noise, which is random sound output with equal power across the entire frequency spectrum. The OPL2’s output has slightly higher frequency response at the low and high edges of the spectrum, making the result something between white noise and gray noise, which is equal loudness across the spectrum.

The relationship between power and loudness is explored in a bit more detail later.

Most instruments in common use have some amount of feedback to add distinctiveness to the sound. The exceptions tend to be tonal percussion elements like the bass drum and low tom-toms.

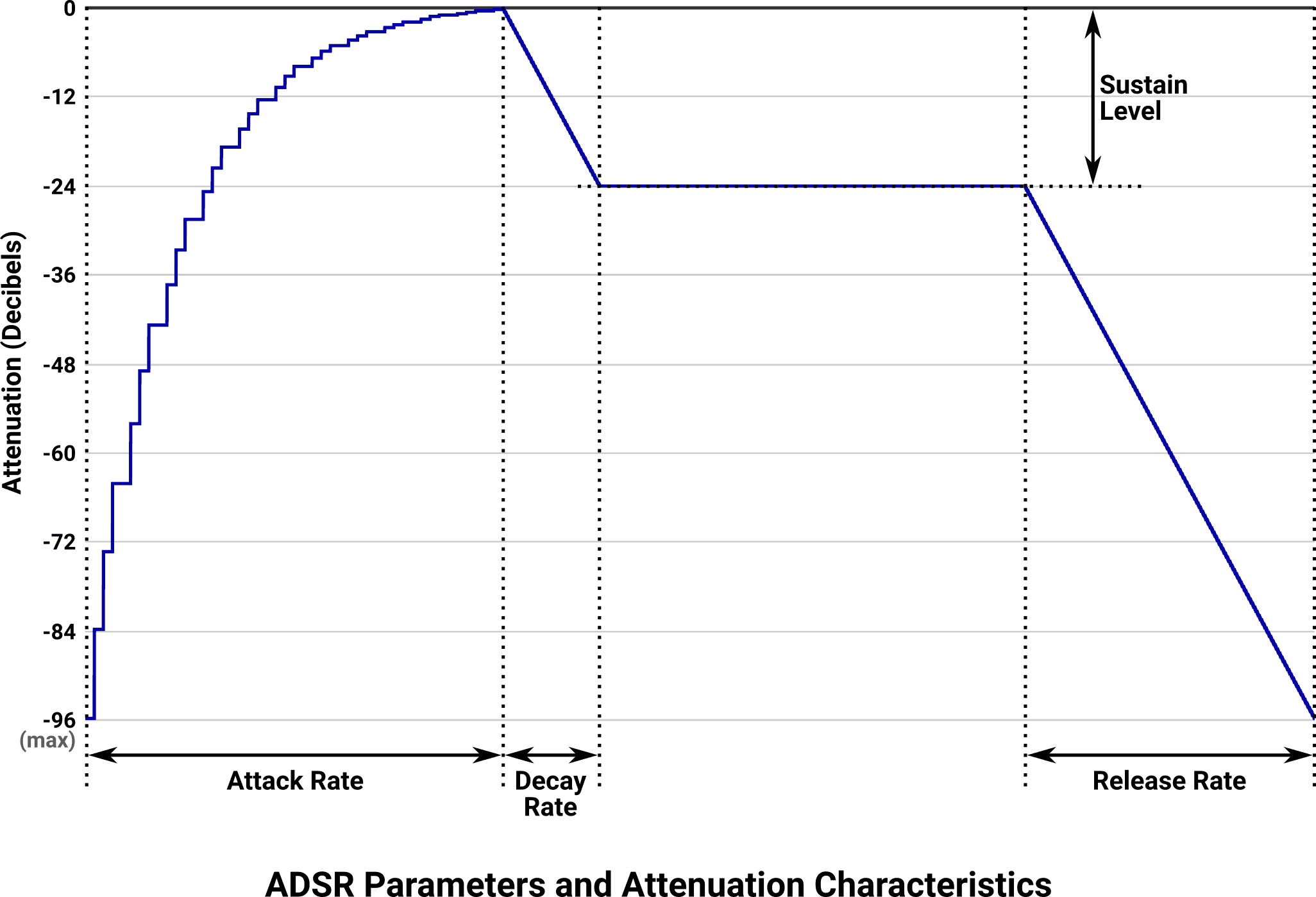

Envelope

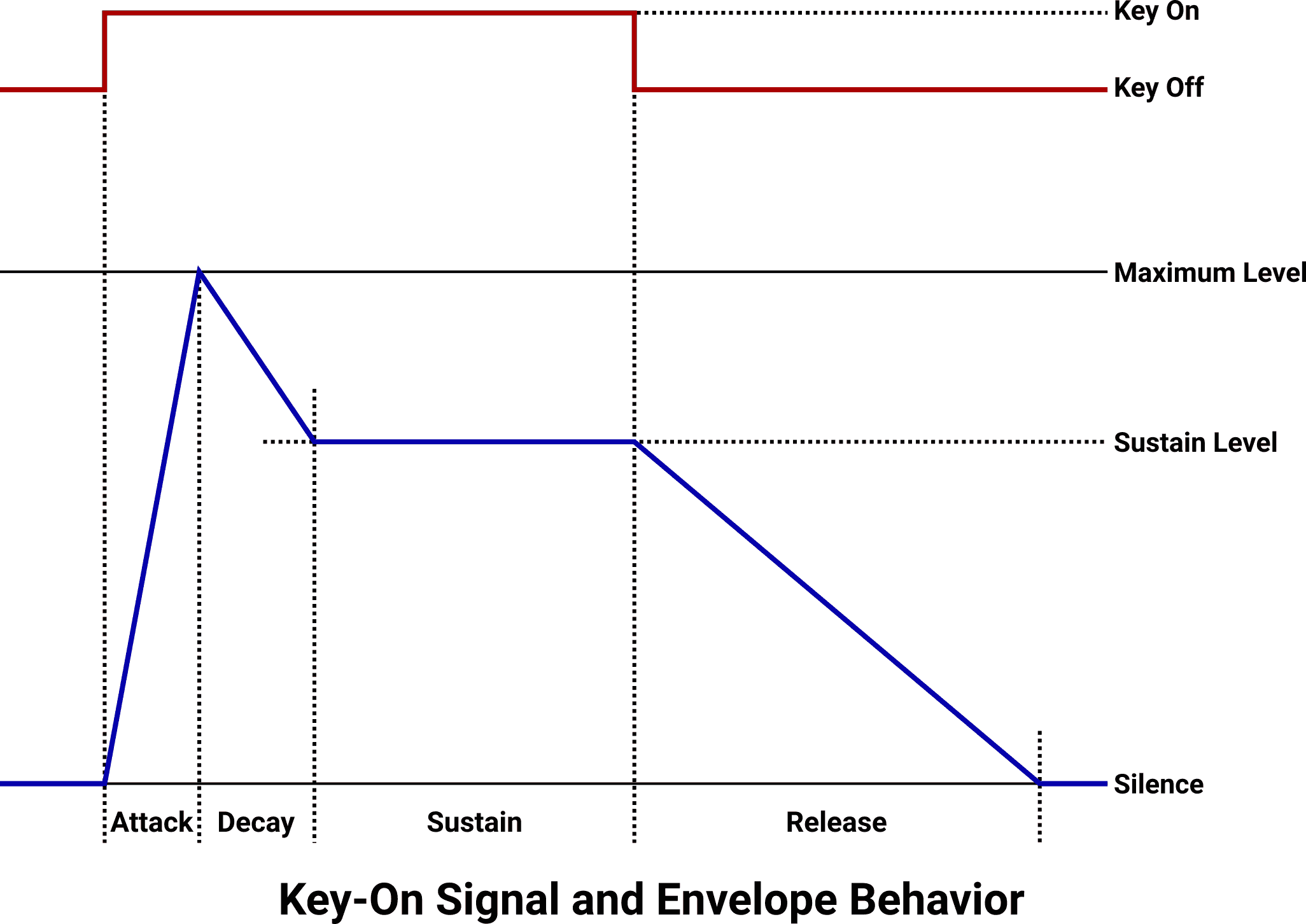

In order to more realistically approximate the behavior of real instruments, most synthesis techniques support amplitude control via envelopes. As each individual note goes through its lifecycle – from initial onset all the way back to silence – the oscillator goes through several distinct stages that affect output amplitude over time. These stages are attack, decay, sustain, and release.

The attack stage begins when a note-on event occurs. This could occur at any time, even if the envelope is already in another stage. During attack, the amplitude of the note begins at silence (or whatever level it was at when the previous envelope was interrupted) and increases at a configurable rate until the amplitude reaches the maximum possible level.

When the maximum attack amplitude is reached, the decay stage begins. During decay, the amplitude of the note decreases at a configurable rate until the amplitude reaches the sustain level.

When the sustain level is reached, all envelope processing is paused. The amplitude is held at the sustain level for as long as the composer holds the note on.

When a note-off event occurs, regardless of the stage the envelope is currently in, the release stage begins. The amplitude of the note decreases at a configurable rate until it becomes silent, at which point the envelope has completed its lifecycle and becomes idle again.

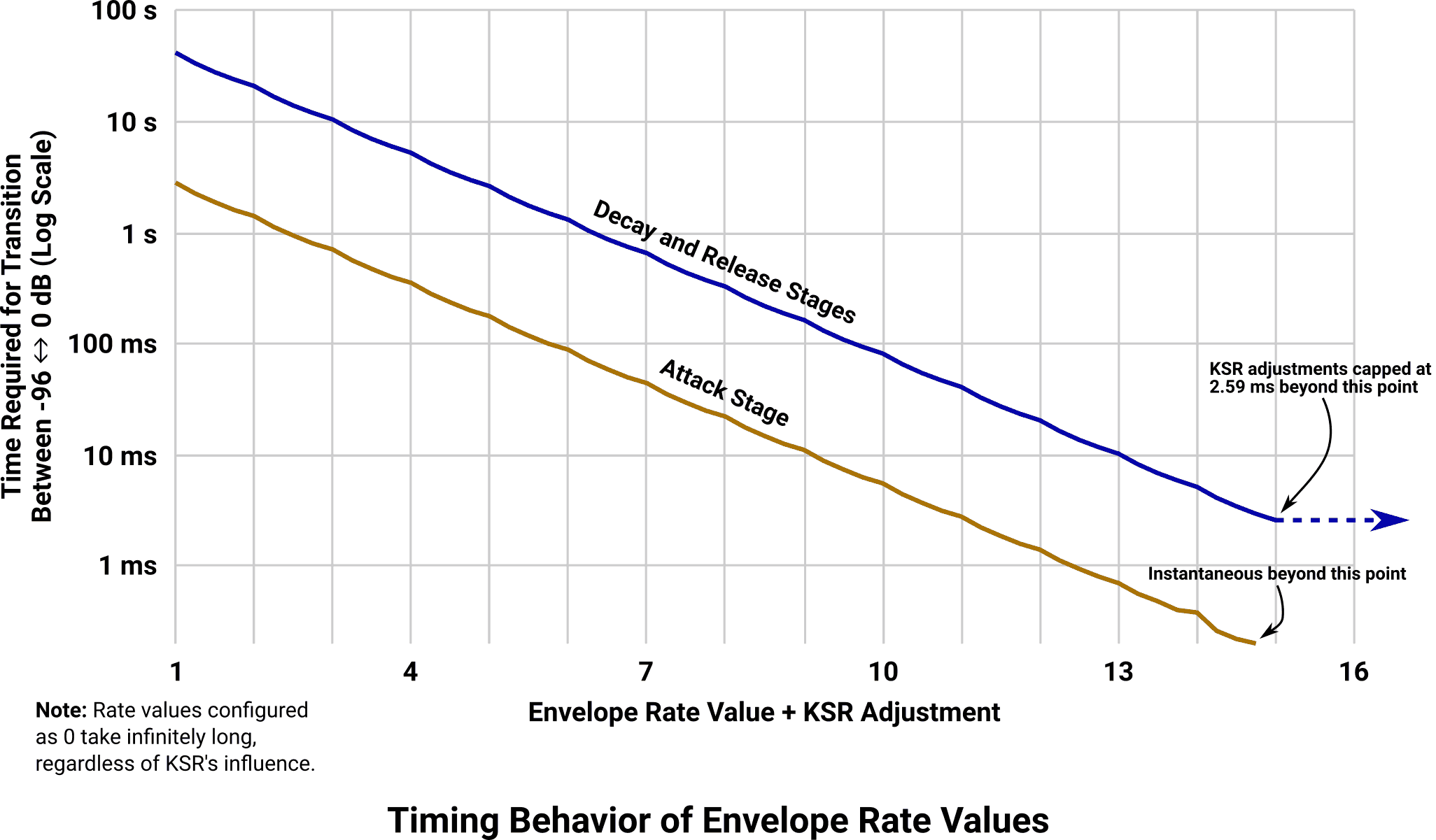

Higher rate values cause faster changes in amplitude, including instantaneous jumps at extreme settings. Lower rate values cause more gradual amplitude changes. Zero is a permissible rate, which has the effect of artificially holding the envelope in a stage that it wouldn’t normally stay in, which can be used for interesting effects.

Visually, the interaction between note events (often called Key On and Key Off signals) and envelopes looks like the following:

The combination of envelope attack, decay, release, and sustain is commonly referred to as ADSR. It’s important to bear in mind that attack/decay/release are rates (amounts of change over time) while sustain is a level (amplitude scaling value). Taken together and configured appropriately, envelopes can create surprisingly convincing simulations of real instrument behavior.

Envelopes are often used in conjunction with FM techniques to create more sophisticated sounds. Depending on the desired effect, the modulator could have very different ADSR settings than the carrier, allowing for the phase of the output to evolve independently of the overall sound level.

Key Scaling

On the subject of simulating real instruments, the OPL2 also supports two slightly more arcane settings: key scaling of rate (KSR) and key scaling of level (KSL). As convoluted as the documentation tries to make it, the underlying concept is surprisingly straightforward: lower notes behave differently than higher notes do. These two settings aim to replicate this behavior with relatively few parameters.

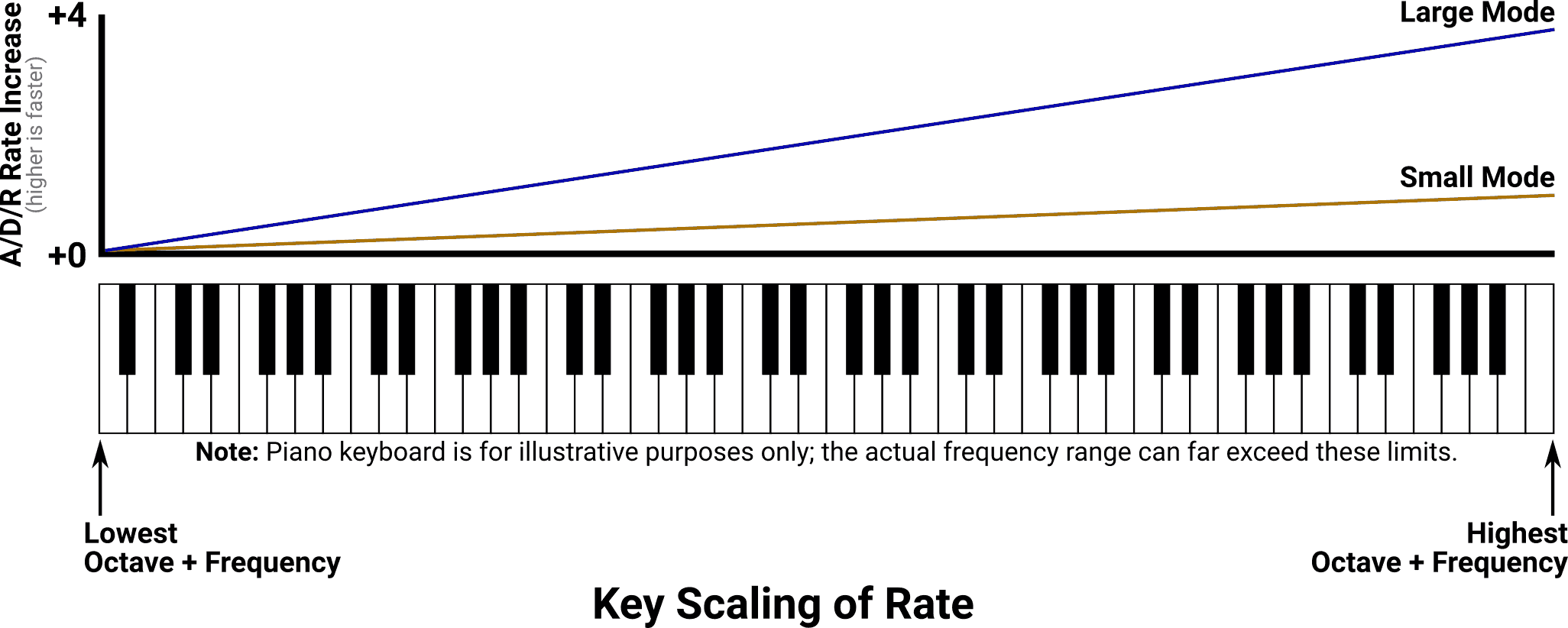

Key scaling of rate adjusts the ADSR rate parameters according to the frequency of the note that is being played. The lowest notes use the original unmodified envelope values, while higher notes have their rates increased (causing their envelopes to progress faster). The higher the note frequency, the more the ADSR rates are sped up. KSR has two possible options: large or small (it is not possible to entirely disable it). In large mode, rates on the highest notes are increased by almost four units. In small mode, the maximum increase is just under one unit.

Note: The exact definition of a rate “unit” is… complicated. It’s explained a little more precisely later on this page.

The piano keyboards in this diagram (and the one that follows) are illustrative and not necessarily to scale. It’s possible to configure the OPL2 to span a much wider frequency spectrum than the piano is capable of, and the scaling graphs would follow that range accordingly.

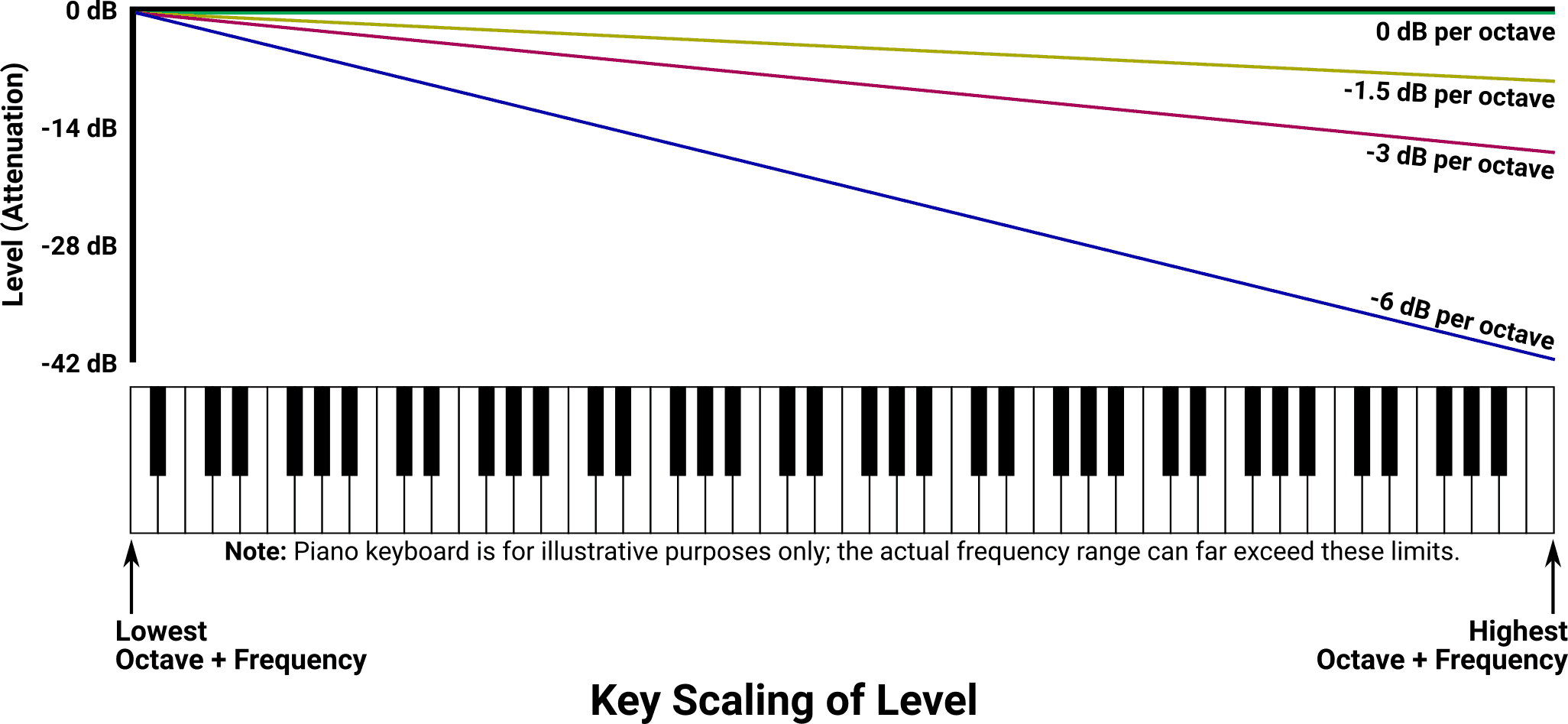

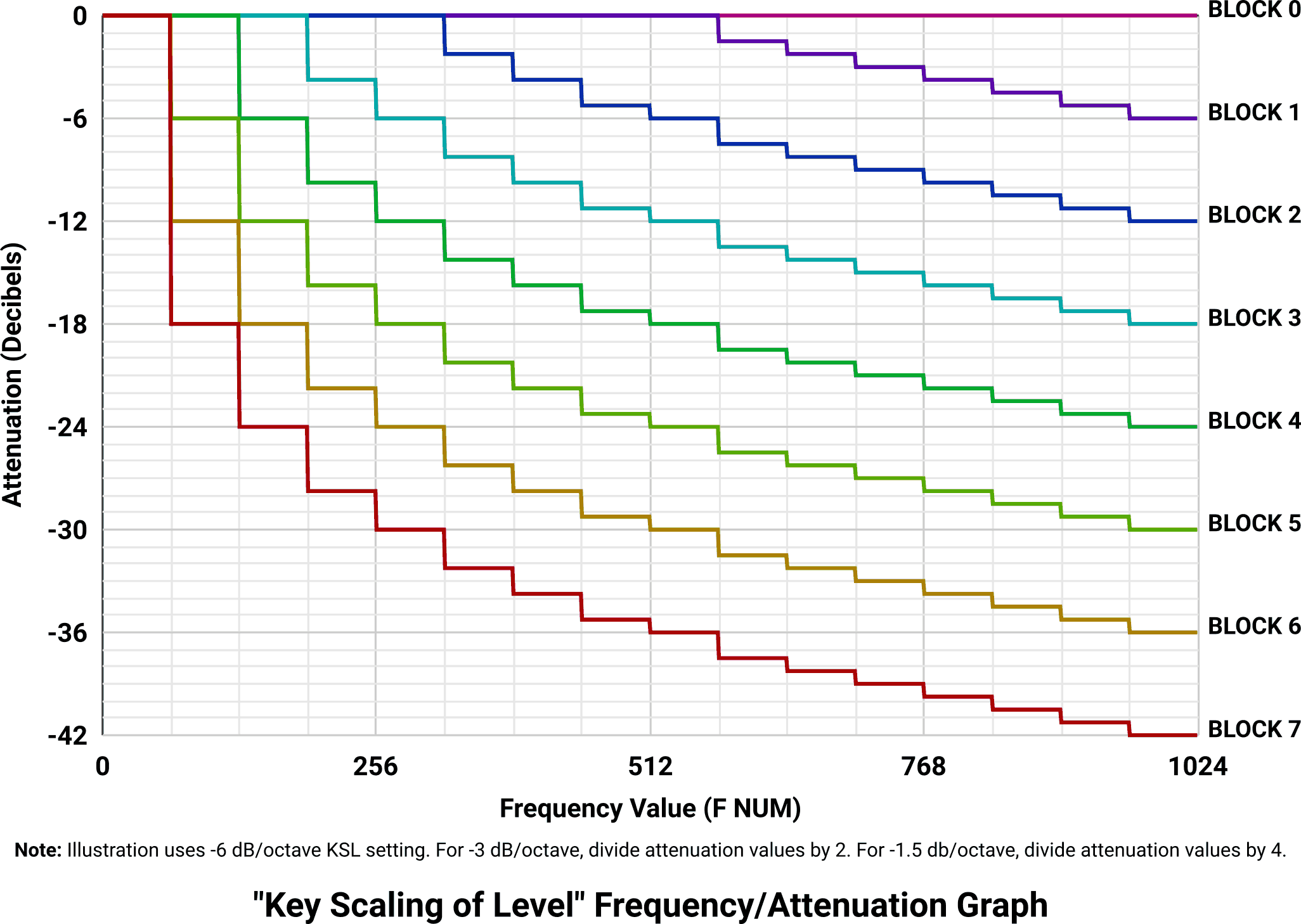

Key scaling of level simulates the tendency of higher notes to play more quietly, and it does this by reducing the amplitude of notes as their frequencies get higher. KSL can be switched off if desired, or set to one of three levels.

The unit “dB” is an abbreviation for decibel, which is described in detail a bit later. For the purposes of this concept, 0 dB is “no reduction in level” and -42 dB is roughly halfway between the loudest and quietest perceived volume available.

Waveforms

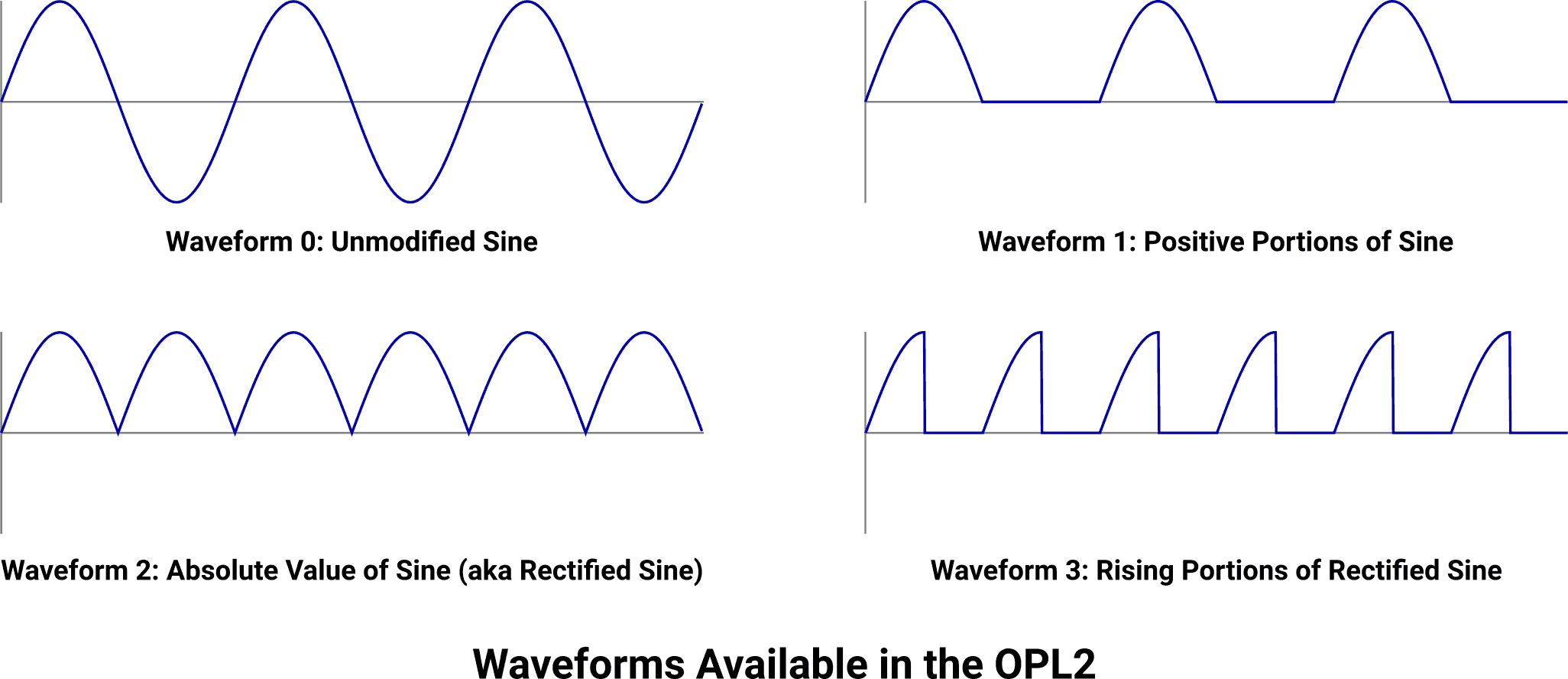

The OPL2 is only capable of producing sine waves, but it can do a few manipulations to the function’s basic shape to produce other waveforms. In total, four waveforms can be produced:

The first wave is the standard sine wave, unmodified. Silencing the negative portions of the wave produces a “half” sine. By instead taking the absolute value of the sine wave, a rectified sine is produced. Finally, by taking the rectified sine wave and silencing the areas with negative slope, a “half-rectified” sine is generated. Each of these has a harsher and more harmonically rich sound compared to the sine function they are derived from.

OPL2 Waveforms: Sine, Half Sine, Rectified, Half-Rectified (Download MP3, AAC, or WAV.)

The modified waves do not contain any negative values, which has the effect of reducing the overall travel distance of the speaker and making them sound somewhat quieter than the pure sine wave. The added sonic character, which could be described as “brightness” or “harshness” by some, compensates for this loss.

Frequencies and Amplitudes, Mathematically

Up until this point, we’ve been treating the units for frequency and amplitude a little loosely. As the description of the OPL2 becomes more concrete, it’s going to be necessary to understand precisely the quantities being measured and how they relate to real sounds.

Frequency

As briefly mentioned earlier, frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) and it describes the number of times a signal repeats itself in one second. The inverse of frequency is the period, which is the amount of time required for one repetition of the signal. This is all pretty cut and dry, and everything makes good clear linear sense until the signal reaches our ears. Human ears are logarithmic.

The distance between the notes B and C on the lowest end of a piano keyboard is about 1.8 Hz. The human ear can detect that difference. On the high end of that same piano, the distance from B to C is almost 235 Hz. Even a well-trained ear would be unable to detect if one of those high keys was 1.8 Hz out of tune without comparing it to a reference frequency – and even then it would be tough to do. Human hearing simply has better resolution at lower frequencies.

Hearing (and physical objects) are also highly responsive to octaves, each of which is a doubling of any frequency. So the first octave of 100 Hz is 200 Hz, followed by another doubling to 400, then 800, and up to 1,600 Hz and so on. Musically, all frequencies in a given octave series sound sort of “the same” – if you’ve ever tried to sing along to a song that was too low for your vocal range, and you compensated by jumping up to a higher set of notes that you could sing comfortably, that’s an octave.

Western musicians decided a long time ago that each octave should have 12 note divisions in it. The rules about how those 12 notes should be utilized came later, but the 12-note octave became the bedrock upon which everything else was built. The intervals between each note were chosen so that every single note was double the frequency of the note 12 spaces to the left, and half the frequency of the note 12 spaces to the right. They accomplished that minor miracle with the following formula: Frequency of note n = (12√2)n × 440 Hz

The 12th root is because our octave is divided into 12 notes, and 440 Hz is the reference frequency of the A above middle C (sometimes called A4). The arrangement works correctly if a different frequency is used, but 440 Hz is the standard that musicians agreed on. The number n is the distance (in note steps) away from the reference note – positive when moving up the keyboard, and negative when moving down.

If we wanted to find the frequency of the note that was five steps below A4, we would calculate (12√2)-5 × 440 Hz ≈ 330 Hz. By the same rules, the frequency of the note seven steps above A4 is (12√2)7 × 440 Hz ≈ 660 Hz. It just so happens that “five steps below” plus “seven steps above” equals 12 steps, and the two calculated frequencies are one octave apart, give or take some rounding error.

The formula can be inverted: Steps to note n = 12 × log2(f ⁄ 440 Hz). Here f is some frequency in hertz, and n is the note-step distance (again positive or negative) away from the A4 reference note.

Amplitude

We’ve been taking the output of the sine function, calling it “amplitude” or “level,” and passing it directly to a speaker that moves proportionally by the same amount. This much is actually accurate, but once again it is not the way our ears perceive things. Human ears are able to detect surprisingly faint sounds, while at the same time tolerating (at least for brief periods) other sounds that are many orders of magnitude louder. As with frequency, the response can best be modeled as a logarithmic one.

Hearing roughly follows a power-of-ten logarithmic curve. This ratio is measured in units called decibels (dB), and every 10 dB represents a halving or a doubling of the perceived loudness of any sound. Absolute measurements of sound pressure in air range from about 5 dB (too quiet to be audible for most people) to about 190 dB (will literally rip your inner ear apart).

In electrical circuits, and computer applications that interact with them, decibels work a little differently. In this universe, 0 dB represents the absolute maximum amount of power (and loudness) that the hardware can faithfully and continually produce. To create lower volumes, the output is attenuated by some amount. In terms of voltage, waveform sample values, and speaker movement, every 6 dB of attenuation exactly halves the output voltage. A given output voltage can only be halved so many times before the level drops to the point where it is indistinguishable from background noise. This has some interesting relationships to digital audio as well – a 16-bit sample value can only be halved 16 times (96 dB attenuation) before it becomes zero (silence).

In everything relating to the OPL2, the rule is that 6 dB of attenuation halves the output level, which also halves the voltage and speaker travel distance. How that is perceived by the listener in context, and how it should be utilized by the composer of the music, is more of a subjective choice than anything else.

You’ll often see levels written like “-12 dB,” which is a shorthand representing 12 decibels of attenuation (or, as we just learned, one-quarter of the maximum output level otherwise attainable at 0 dB of attenuation).

Anyway, Here’s the OPL2

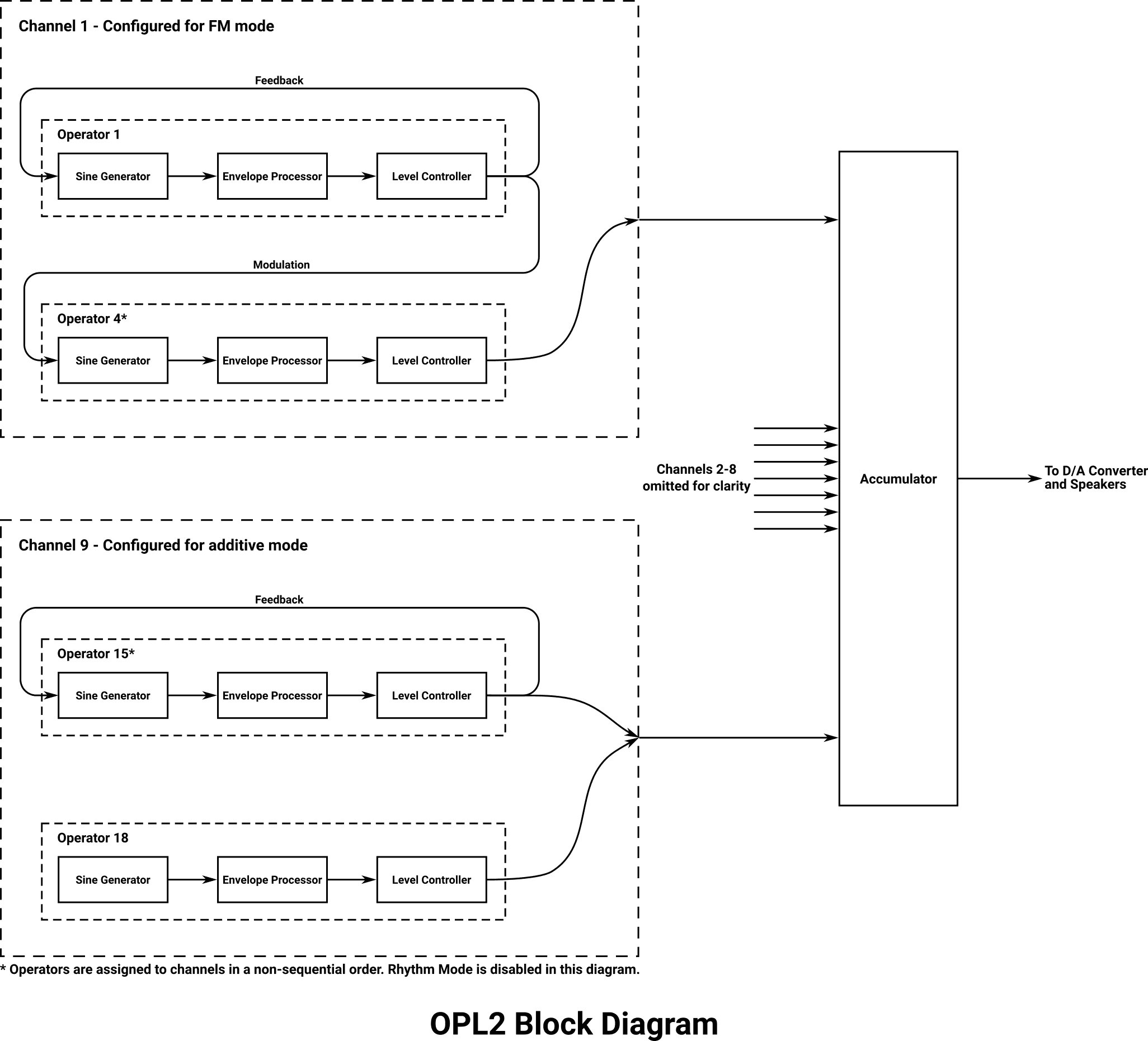

Theory becomes practice now. The OPL2 is a real-time FM synthesis chip that is reprogrammed on the fly while playback occurs. It contains 18 operators, each consisting of a sine wave generator (oscillator), an envelope processor, and a level controller. Each operator is self-contained and functionally independent. The OPL2 is organized into nine channels, each managing two of the available operators. Each channel can control how its operators are connected to each other: either serially to produce FM sounds, or in parallel for additive synthesis. The output of all nine channels is summed together to produce a 13-bit floating-point sample value that an external digital-to-analog converter (like the Yamaha YM3014) decodes into an electrical signal for the speaker circuit.

The OPL2 has an 8-bit data bus that supports both reading and writing from the host system’s CPU. When read, the OPL2 reports the state of its two internal timers. Writing is a two-step operation: the host must first write the address of the 8-bit register it wants to program, then it must write the 8-bit value that should be placed into that register. The updated value becomes audible immediately. There is no provision to read back the contents of arbitrary registers.

There are three kinds of registers: chip-wide registers, per-channel registers, and per-operator registers. The chip-wide registers each have a single address and modify a parameter that influences the behavior of the chip as a whole. Channel registers modify parameters that are channel specific, and each of these register types occupies nine positions in the address map – one for each channel. Similarly, operator registers control parameters for a single operator, and there are 18 positions used in the address map for each of these register types.

Chip-Wide Registers

The OPL2 contains 18 parameters that influence the behavior of the entire chip. Each of these register values either changes a sub-circuit that the chip only contains one instance of, or controls a setting that applies universally across all channels and/or operators.

| Register Address | Bit Position | Acronym | Range | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01h | 5 | WSE | Off/On | “Waveform Selection” Enable |

| 02h | 7–0 | TIMER 1 | 0–255 | Timer 1 Preset Value |

| 03h | 7–0 | TIMER 2 | 0–255 | Timer 2 Preset Value |

| 04h | 7 | RST | Off/On | Interrupt Reset Command (must be sent in isolation) |

| 04h | 6 | T1 MASK | Off/On | Timer 1 Mask |

| 04h | 5 | T2 MASK | Off/On | Timer 2 Mask |

| 04h | 1 | T2 START | Off/On | Timer 2 Enable |

| 04h | 0 | T1 START | Off/On | Timer 1 Enable |

| 08h | 7 | CSM | Off/On | Composite Sine Wave Speech Modeling Enable |

| 08h | 6 | NOTE SEL | 0–1 | Note Select (Keyboard Split) Position |

| BDh | 7 | AM DEP | 0–1 | Amplitude Modulation (Tremolo) Depth |

| BDh | 6 | VIB DEP | 0–1 | Vibrato Depth |

| BDh | 5 | R | Off/On | Rhythm (Percussion) Mode Enable |

| BDh | 4 | BD | Off/On | Bass Drum Key-On |

| BDh | 3 | SD | Off/On | Snare Drum Key-On |

| BDh | 2 | TOM | Off/On | Tom-Tom Key-On |

| BDh | 1 | TC | Off/On | Top Cymbal Key-On |

| BDh | 0 | HH | Off/On | Hi-Hat Key-On |

When a read command is issued to the OPL2, a status byte is returned. Since there is only one single readable register in the entire chip, it is not necessary (or possible) to request a specific register address to read from.

| Bit Position | Acronym | Range | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | IRQ | Off/On | Interrupt Requested |

| 6 | T1 FLAG | Off/On | Timer 1 Overflow Occurred |

| 5 | T2 FLAG | Off/On | Timer 2 Overflow Occurred |

Per-Channel Registers

The OPL2 contains nine instances of the following six parameters, one group for each channel in the chip. The values here either adjust both of the channel’s operators in tandem, or influence the way the two operators are connected to each other.

| Register Address | Bit Position | Acronym | Range | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A0h + channel | 7–0 | F NUM L | 0–255 | Frequency Value (low byte) |

| B0h + channel | 5 | KON | Off/On | Channel Key-On |

| B0h + channel | 4–2 | BLOCK | 0–7 | Octave (Block) Value |

| B0h + channel | 1–0 | F NUM H | 0–3 | Frequency Value (high 2 bits) |

| C0h + channel | 3–1 | FB | 0–7 | Feedback Depth |

| C0h + channel | 0 | C | 0–1 | Connection Type |

Per-Operator Registers

The OPL2 contains 18 instances of the following 12 parameters, one group for each operator in the chip. These allow for independent control of each modulator, carrier, or additive oscillator (depending on how the chip and its channels have been configured).

| Register Address | Bit Position | Acronym | Range | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20h + operator | 7 | AM | Off/On | Amplitude Modulation (Tremolo) Enable |

| 20h + operator | 6 | VIB | Off/On | Vibrato Enable |

| 20h + operator | 5 | EG TYPE | 0–1 | Envelope Generator Type |

| 20h + operator | 4 | KSR | 0–1 | “Key Scaling of Rate” Value |

| 20h + operator | 3–0 | MULTI | 0–15 | Frequency Multiplier Value |

| 40h + operator | 7–6 | KSL | 0–3 | “Key Scaling of Level” Value |

| 40h + operator | 5–0 | TL | 0–63 | Total Level Value |

| 60h + operator | 7–4 | AR | 0–15 | Attack Rate |

| 60h + operator | 3–0 | DR | 0–15 | Decay Rate |

| 80h + operator | 7–4 | SL | 0–15 | Sustain Level Value |

| 80h + operator | 3–0 | RR | 0–15 | Release Rate |

| E0h + operator | 1–0 | WS | 0–3 | Waveform Selection |

The assignments between channels and operators, and between operators and their register offsets, is not contiguous and not straightforward to explain. The table below shows the modulator/carrier operator pairs for each channel, and the offsets used to address them in per-operator register writes:

| Channel | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel Register Offset | 0h | 1h | 2h | 3h | 4h | 5h | 6h | 7h | 8h | |||||||||

| Operators (Modulator/Carrier) | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 9 | 12 | 13 | 16 | 14 | 17 | 15 | 18 |

| Operator Register Offset | 0h | 3h | 1h | 4h | 2h | 5h | 8h | Bh | 9h | Ch | Ah | Dh | 10h | 13h | 11h | 14h | 12h | 15h |

Note: Operator register offsets 6–7h, E–Fh, and anything ≥ 16h are undefined and perform no function.

The arrangement of operators is a consequence of the OPL2’s design. The chip only contains one physical instance of an operator circuit, which must be utilized 18 times to generate all of the values that comprise an output sample. The operator index arrangement is related to the order that this operator circuit processes the data internally.

Clock and Timing

The OPL2 chip requires an external high-frequency oscillator to govern its operation and to serve as the master clock for all frequency-based calculations. As installed in the AdLib card, the master clock runs at approximately 3.58 MHz and the output sample rate is 49,716 Hz. Any conversions to/from a musical frequency must incorporate this sampling frequency to keep proper tuning.

The PC’s clock strikes again.

At first glance, 49,716 Hz seems like a pointlessly arbitrary number. But it’s actually derived in a surprisingly straightforward way. As detailed on the Programmable Interval Timer/PC speaker page, the PC’s clock generator circuitry is based around a 315 ⁄ 22 MHz (14.3 MHz) crystal, which was widely available and cheap due to its use in NTSC color television equipment. The AT bus uses this frequency, unmodified, as the “OSC” signal. The AdLib, lacking any timing circuitry of its own, cleverly passes this signal through a 74LS109 dual flip-flop that divides the frequency by four, yielding 315 ⁄ 88 MHz (3.58 MHz).

The OPL2 chip requires 72 clock cycles to generate one sample of output data. This works out to ([315 ⁄ 88 MHz] ⁄ 72) 49,715.90 Hz, which is rounded to 49,716 Hz in typical calculations.

The OPL2 chip requires a fixed amount of “recovery” time after a write operation. The host must wait for 12 master clock cycles after writing a register address before it can write data, and it must wait 84 cycles after writing a data byte before it can write anything else. At AdLib clock rates, these wait times are about 3.4 µs and 23.5 µs, respectively. If these delays are ignored, there’s no guarantee that a write operation will have the intended effect.

On-Board Timers

A fair number of the chip-wide writable registers (and the entirety of the readable registers) are there to support a pair of configurable timers. Timer 1 increments its counter once every 80 µs and Timer 2 increments one-fourth as fast – every 320 µs. Each timer counter is eight bits wide, and whenever either of them overflows and wraps back to zero, a flag value is set to indicate the overflow and that timer’s Preset Value is reloaded into the counter. Using this arrangement, Timer 1 could be configured to overflow at a rate anywhere between 49 Hz and 12.5 kHz, while Timer 2 could be configured for 12–3,125 Hz. When either timer overflows, an interrupt request is also raised at the hardware level. The AdLib doesn’t listen to this signal, however, so there is no way for the host system to know about these timer events without resorting to polling.

The Timer 1/2 Preset Value registers control the counter value that is reloaded during each overflow, which influences the resulting overflow rate – higher values produce more frequent overflows. The Timer 1/2 Mask settings control whether the chip raises an interrupt when that particular timer overflows. The Timer 1/2 Enable settings pause or unpause counting for that timer. If an interrupt has previously occurred, the Interrupt Reset command will acknowledge it and reset all flags in preparation for a subsequent interrupt request.

The host can read the Timer 1/2 Overflow Occurred flag bits to determine if one of the timers has overflowed since the last interrupt reset, and which timer it was. If the host doesn’t care about the specific timer that triggered the interrupt, it can simply read the Interrupt Requested bit, which turns on if either of the timer flag bits have turned on.

In common operation, nothing is triggered by either of these timers and they do not influence the sound produced by the chip. They serve no outwardly apparent purpose, which is why many sources gloss over the fact that they exist. The most common use of these timers is actually to detect the AdLib in the first place, since this is the only means of bidirectional communication the programmer has to determine if an AdLib or AdLib-like piece of hardware is installed at a particular I/O address.

Composite Sine Wave Speech Modeling

The OPL2 and the original OPL (YM3526) chips support a composite sine wave speech synthesis mode (CSM). Nobody, including your humble author, seems to really understand how this was supposed to work or what it may have sounded like. General consensus seems to be that it was hard to do and sounded bad in practical use, so take that as you will.

Apparently CSM required all channels to be configured in additive mode with no active key-on signals. Whenever Timer 1 overflowed, it would briefly strobe the Key-On signal for every channel. That’s about all I was able to find in the original documentation. This feature was removed in the OPL3 (YMF262) and none of the software emulators I’m aware of have implemented it.

Waveform Selection

Yamaha’s OPL and OPL2 are actually identical for all practical purposes and can be interchanged without difficulty. The only thing differentiating the OPL2 is the ability to choose between four different sine waveform functions. The original OPL can only produce unmodified sine waves.

Changing the waveform involves two parameters: The Waveform Selection value on one of the operators, and the “Waveform Selection” Enable setting at the chip level. If “Waveform Selection” Enable is not turned on, changes to a Waveform Selection parameter are ignored and the OPL2 behaves identically to an OPL – only using waveform 0.

The available waveforms for each operator are:

| Waveform Selection | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Unmodified sine |

| 1 | Positive portions of sine |

| 2 | Absolute value of sine (aka “Rectified” Sine) |

| 3 | Rising portions of rectified sine |

Tremolo

The OPL2’s tremolo effect is controlled by two parameters. The AM/Tremolo Depth parameter at the chip level changes the depth used chip-wide:

| Tremolo Depth | Attenuation Range |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 – -1.1 dB |

| 1 | 0 – -4.9 dB |

The AM/Tremolo Enable parameter on each operator controls whether tremolo should be applied to that operator. Regardless of the depth setting, the tremolo effect runs at 3.7 Hz and every operator’s tremolo phase is locked in sync.

Vibrato

Vibrato works similarly to tremolo. The chip-wide Vibrato Depth parameter sets the amount of frequency adjustment applied. This is accomplished by adding or subtracting a certain number of cents to the frequency specified in the channel’s “F NUM” value. (One cent is equal to 1/100th of a note step.)

| Vibrato Depth | Frequency Range |

|---|---|

| 0 | “F NUM” ±7 cents |

| 1 | “F NUM” ±14 cents |

The Vibrato Enable parameter on each operator controls whether vibrato is enabled there. The vibrato frequency is 6.07 Hz and the vibrato phase is locked in sync across all operators.

Frequencies, Octaves, and Notes

To control the actual frequency and enablement of the notes played on a channel, four parameters are involved. The first, Frequency Value (or “F NUM”) is a 10-bit quantity which is split between a full 8-bit register and two bits of another register. Taken together, the Frequency Value can be in the range of 0–1,023. Another channel parameter, Octave (or “BLOCK”), shifts the binary digits in the Frequency Value to the left by a certain number of positions. The Octave value can be any integer between 0 (meaning no shift occurs) up to 7 (shift to the left by seven binary digits). This has the effect of multiplying the Frequency Value by 2BLOCK, which also has the effect of moving the note frequency up by one musical octave for every one Octave Value.

To convert the Frequency and Octave Values into the frequency they represent, the formula f = FNUM × 49,716 ⁄ 220 - BLOCK can be used. Here f is the audible frequency that will be played (in hertz), FNUM is the Frequency Value as programmed into the OPL2’s registers, and BLOCK is the Octave Value. The constant 49,716 is the sampling frequency of the AdLib’s OPL2.

The inverse of this formula is more commonly seen in documentation for AdLib programming: FNUM = f × 220 - BLOCK ⁄ 49,716. The programmer has to do a bit of work here – not only is it necessary to translate musical note names into frequencies in hertz before even starting the conversion, but they also need to select a value for BLOCK that won’t cause FNUM to overflow on high notes, while also providing enough resolution to get accurate tuning on low notes. It’s a bit of a delicate trade-off.

Note: The value chosen for FNUM also interacts with the Note Select (Keyboard Split) parameter, explained below. The programmer should consider how the chosen FNUM value will propagate through this setting to influence the envelope rates.

Next, each operator has a Frequency Multiplier Value which can further manipulate the frequency being played. This is the only parameter that allows the two operators on a channel to run at different frequencies – all other frequency-control parameters are set at the channel level and apply to both operators in unison.

| Frequency Multiplier Value | Operator Frequency Multiplied By… |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0.5x |

| 1 | 1x |

| 2 | 2x |

| 3 | 3x |

| 4 | 4x |

| 5 | 5x |

| 6 | 6x |

| 7 | 7x |

| 8 | 8x |

| 9 | 9x |

| 10 or 11 | 10x |

| 12 or 13 | 12x |

| 14 or 15 | 15x |

The final piece of the puzzle is each channel’s Key-On parameter. (The word “key” here is used in the sense of, say, a piano key.) When this is turned on, both operators on the channel begin voicing their output, each starting their ADSR envelopes at the beginning of the “attack” stage. As long as the Key-On parameter remains enabled, the envelopes will follow their pre-programmed rates and stages, controlling the output of the oscillators along the way. The oscillators will play for as long as the Key-On parameter remains on, provided their envelopes are not programmed to silence the sound prematurely.

When the Key-On parameter is turned off, the envelopes jump to their “release” stage and begin the process of silencing the oscillator outputs.

Operator Connections and Feedback

Each channel contains a pair of closely-related parameters: Connection Type and Feedback Depth. These control how the channel’s two operators are connected together. Connection Type can be one of the following:

| Connection Type | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Frequency Modulation mode. Operator 1 is the modulator, whose instantaneous output amplitude is fed into operator 2 as a phase adjustment in the range ±8π. Operator 2 is the carrier, whose output becomes the output for the channel as a whole. |

| 1 | Additive mode. Operator 1 and operator 2 share no phase adjustments. The outputs of both operators are added together, and this sum becomes the output for the channel as a whole. |

In both modes, operator 1 (and only operator 1) supports an optional amount of feedback. Feedback is computed by taking the previous two samples produced by operator 1, adding the samples’ amplitudes together, and scaling the result based on the configurable Feedback Depth. The result – which could be anywhere between zero and ±4π depending on the amplitude of the previous samples and the amount of depth configured – is added to the phase offset of operator 1 as its next sample is computed.

| Feedback Depth | Phase Offset Range |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 (feedback disabled) |

| 1 | ±π/16 |

| 2 | ±π/8 |

| 3 | ±π/4 |

| 4 | ±π/2 |

| 5 | ±π |

| 6 | ±2π |

| 7 | ±4π |

Rhythm Mode

Rhythm Mode Enable is a chip-wide setting that, when turned on, rewires channels 7–9 to function as five separate percussion instruments. Channel 7 uses FM mode, combining its two operators to produce a bass drum sound. Channels 8 and 9 both switch to additive mode to independently produce a snare drum, tom-tom, top cymbal, and hi-hat. Channels 1–6 continue to operate as usual.

Since there are five percussion instruments, but they’re packed into just three channels, a different mechanism must be used to control their Key-On states. Five bits in register BDh, one per instrument, control the Key-On for each rhythm sound in this mode. The per-operator registers can still be used to tune the sound of each percussion instrument independently, allowing for some degree of customization.

Rhythm mode does not see much use in general, and it is never enabled at any point in any of this game’s music. The reasoning for this varies, with some sources claiming that rhythm mode does not offer enough control over the sound of the drums to create the tones required for many compositions. Other creators (or perhaps the software tools they prefer to use) are simply more comfortable defining their sounds in the confines of FM synthesis alone.

Amplitude Levels

There are two parameters on each operator that control the overall level of output produced. These are the Total Level Value and the “Key Scaling of Level” Value.

The Total Level value, as one could probably surmise, controls the total level of output produced by an operator. This is expressed as an attenuation, where zero means “no reduction” in output level and increasing values (up to the maximum of 63) represent progressively quieter outputs. The exact conversion is 0.75 dB of attenuation per Total Level step, for a range of 0 dB to 47.25 dB of attenuation.

Total Level is really the only avenue of control the programmer has over the absolute volume of notes in a musical phrase, so anything pertaining to volume or velocity (in the MIDI sense of the terms) gets wedged into a Total Level adjustment immediately before each Key-On event.

The “Key Scaling of Level” Value (KSL) manages an effect where higher notes are played back at quieter levels than lower notes. This provides for a more accurate simulation of some types of instruments. KSL values are as follows:

| KSL Value | Attenuation |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 dB (KSL disabled) |

| 1 | 3 dB/octave |

| 2 | 1.5 dB/octave |

| 3 | 6 dB/octave |

Note: These values are defined in a weird order. What can you do.

Rather than go on a long-winded explanation of how the math works, suffice it to say that this setting does what it says it does: Each time the frequency (expressed by “BLOCK” and “F NUM”) doubles, the effective output of the operator is reduced by the number of decibels in the table. At the highest frequencies and the strongest KSL setting, the amount of adjustment can reach -42 dB.

Envelope Rates and Levels

The lifecycle of a note as it goes from Key-On to Key-Off, simply referred to as its “envelope,” involves several rate and level parameters: Attack Rate, Decay Rate, Sustain Level, and Release Rate. Together these are sometimes called “ADSR.” There are also a few other parameters that can scale the rates and influence the transitions between these four stages.

Each operator spends its idle time with its attenuation at the maximum value, producing silence. When a Key-On event occurs, the “attack” stage is entered and the attenuation level is reduced by a specific value (influenced by the attack rate) as each sample is computed. Eventually the attenuation level reaches zero, meaning full output level has been reached, and the “decay” stage begins. From here, the attenuation level is increased by a value influenced by the decay rate, causing the output level to decrease. As the output decays, it is continually compared to the sustain level and, once it matches, the “sustain” stage begins. During sustain, all levels are held at their current values for as long as the note is being held. Eventually, a Key-Off signal arrives, starting the “release” stage. The attenuation level is increased by a value influenced by the release rate, until it reaches the maximum attenuation value. Once the maximum level is reached, the output is silent and the operator becomes idle again.

While the decay and release stages use a linear change in decibel level, the attack is more logarithmic in nature – beginning sharply but slowing down as it “eases” into its peak level. The calculations for the attack use tiny lookup tables and integer math to produce a rather low-resolution stair-step pattern that contributes to the distinctive character of the OPL2’s sound.

The rate units for attack, decay, and release are measured relative to time on a logarithmic scale. A decay or release traveling from zero dB attenuation to max attenuation takes approximately 15 times as long as the attack stage takes to perform the same amount of change. Typically the decay and release stages only need to travel partway through the scale – either from zero dB attenuation to the sustain level, or from the sustain level to maximum attenuation – so many envelopes finish these stages more quickly than the computed graph would suggest.

If any of the three rates are set to zero, the envelope will pause indefinitely in the corresponding stage with no change in output level. This would typically not be done for attacks, since it would result in a note that never became loud enough to hear. It would also be of limited utility for releases, since it would cause notes to stick in the “on” state until another Key-On event restarted the envelope. Similarly, a rate of 15 would produce an instantaneous or almost-instantaneous progression through that particular stage of the envelope.

The Sustain Level parameter is simply an attenuation value, encoded in 3 dB steps for a total range of 0 dB to -42 dB. There is a special case for the value 15, which is interpreted as -93 dB. The higher the Sustain Level value, the quieter the output will be during the sustain stage.

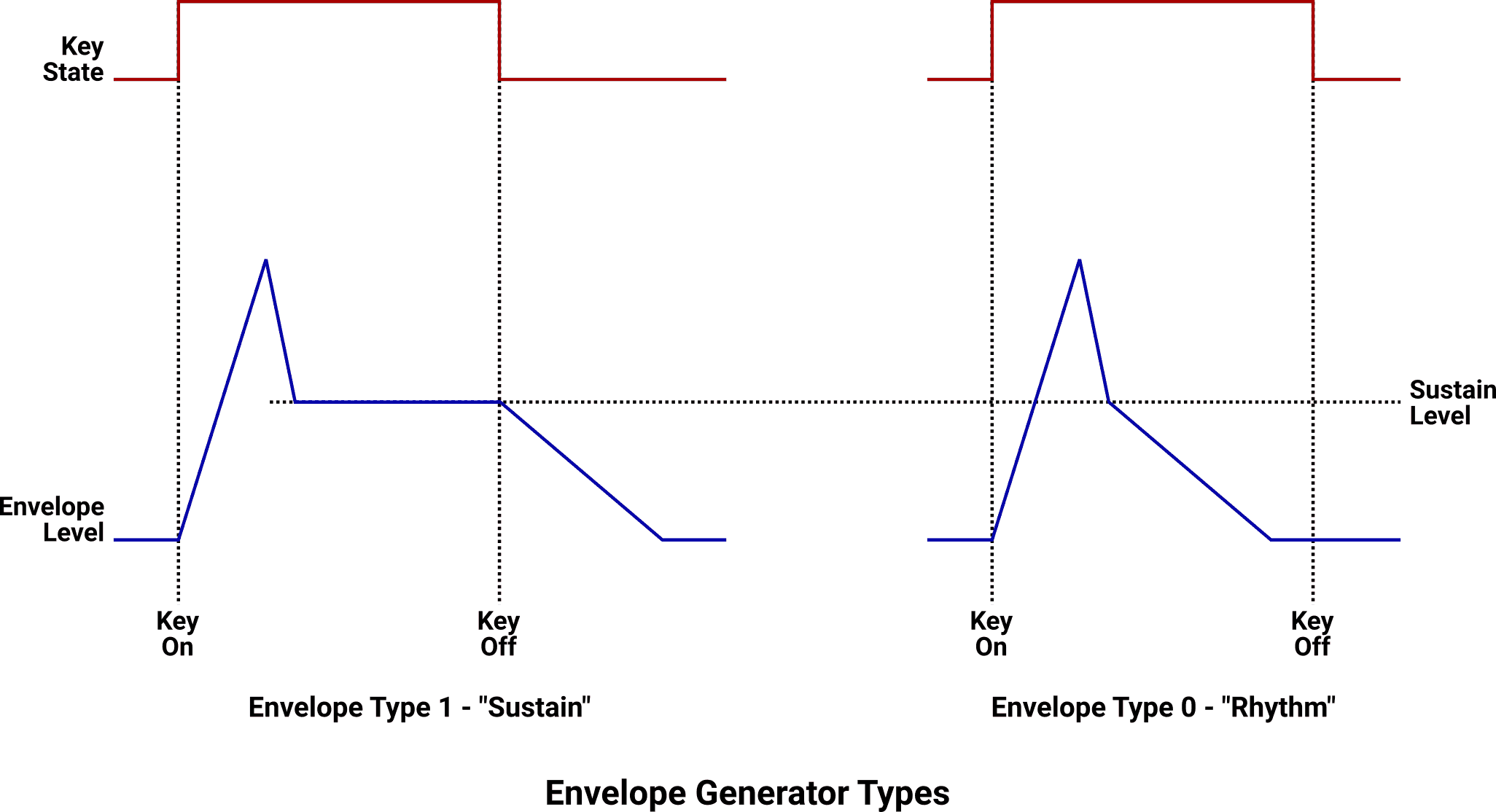

The envelope’s behavior can be further customized by changing the Envelope Generator Type parameter. When this is set to type 1, the envelope functions as we have described it here. When changed to type 0, however, the behavior of the sustain stage changes slightly: Envelope type 0 uses the sustain level as an inflection point where the envelope skips from the decay mode directly to the release mode. Type 0 envelopes do not play sustained tones while the Key-On parameter is held, instead producing relatively short constant-length notes. Due to this behavior, type 0 envelopes are sometimes referred to as “rhythm” or “percussion” envelopes, but that’s not strictly all they can be used for.

The last bit of envelope control available is Key Scaling of Rate (KSR). This is used to speed up all of the rate values on higher-frequency notes to simulate the behavior of real instruments. This cannot be turned off, but it can be switched between producing small or large amounts of change.

The KSR adjustment is calculated by taking the operator’s current Octave Value, shifting it to the left by one bit position (effectively doubling it) and adding the “selected bit” from the operator’s current Frequency Value to the result. This produces an intermediate value between 0 and 15. In small mode (KSR is 0), the result is scaled down by a factor of four, limiting the result to an integer value between 0 and 3. The final result of these calculations is called the key scale value (KSV).

The OPL2 internally uses (RATE × 4) + KSV during each stage of envelope processing to compute an effective rate between 0 and 60 (clamped to that range if any of the values are excessive). The programmer can’t do anything directly with this knowledge, but it does help form an intuition of the relative effect between the programmed attack/decay/release rates and the KSV. Namely, the highest frequencies in large mode could add 3.75 units to the requested rate, while the same frequencies in small mode could add 0.75 units. (And the lowest frequencies, as one might guess, get nothing added in either mode.)

I glossed over the meaning of “selected bit” in the KSV calculation above. This is controlled by the chip’s Note Select (Keyboard Split) Position value: When 0, the “selected bit” is the most significant bit (bit 9) of the Frequency Value. When 1, the “selected bit” is the second-most significant bit (bit 8). This is apparently backwards in the official Yamaha documentation, or every emulator is getting the behavior wrong. Either way, it’s not really something that creates a huge audible difference in the output, and the game never sets Note Select to anything but zero during any of its music.

OPL2 Cheat Sheet

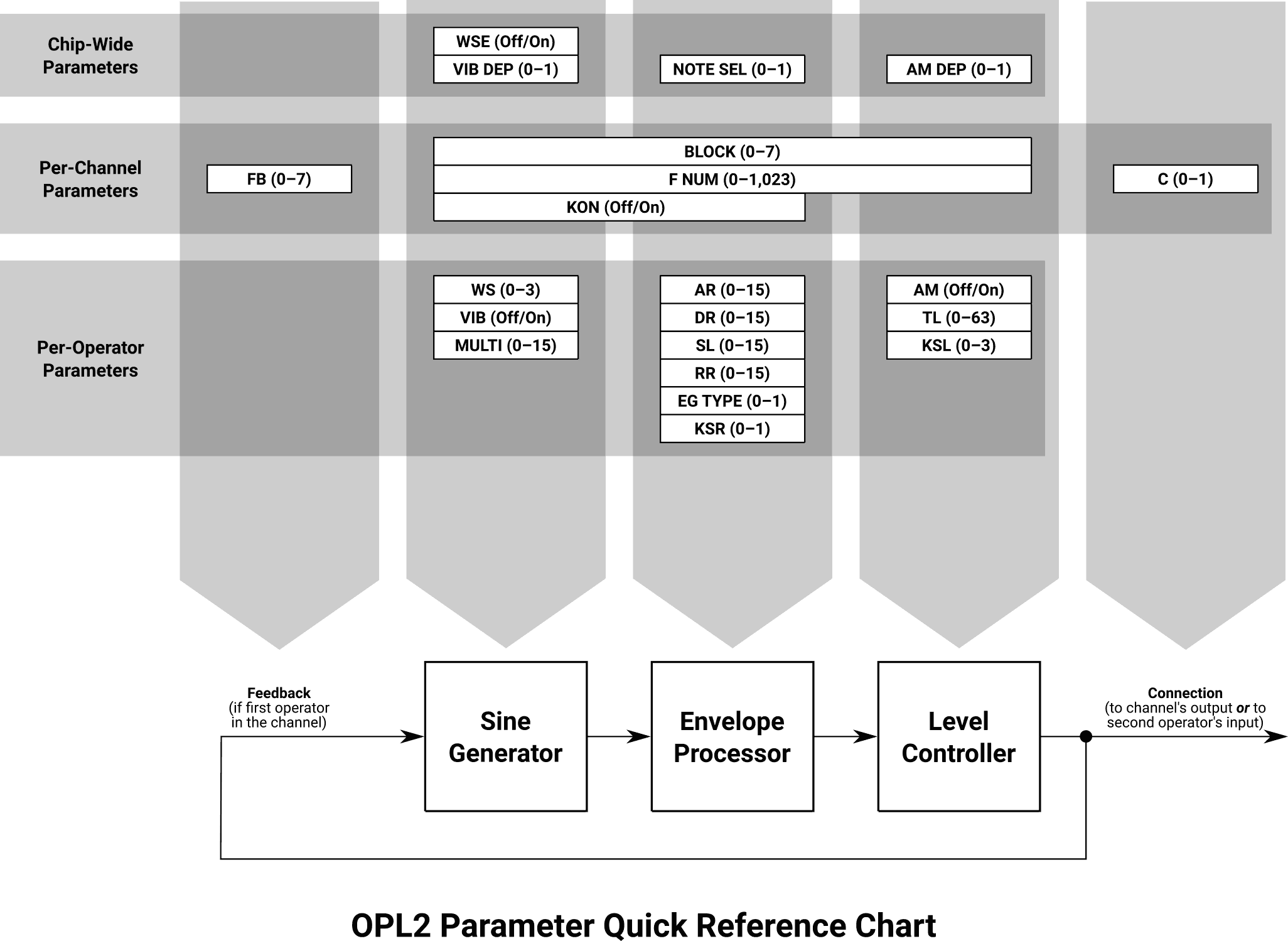

If you followed me this far, this should probably make some amount of sense:

This shows the basic structure of one operator, along with all of the parameters available to configure it. Each parameter is grouped by the register area it is controlled by (chip-wide, per-channel, or per-operator) and which part of the signal chain it affects (sine generation, envelopes, levels, or more than one element.) For clarity, this does not show the parameters related to CSM or Rhythm modes, which are not typically seen in most applications anyway.

The OPL2 isn’t exactly complicated, it just straddles a lot of technical disciplines. It offers a great deal of control over the sounds it produces, but it’s not always friendly or intuitive. But as musicians in the 1980s and 90s showed us, it can do amazing things and make lasting impressions on listeners.

The Anatomy of a Song

The OPL2 has nine channels, meaning it is capable of playing nine simultaneous notes, but the music in this game (like many games of the era) only uses eight of them. Channel 1 is reserved for sound effect playback, which has a unique sort of aesthetic that can be heard in games like Commander Keen episodes four through six, or on some of the bonus items in Wolfenstein 3D. It is unknown if channel 1 was reserved consciously by Bobby Prince (the game’s composer) in anticipation of the possibility of including AdLib sound effects, or if this was a convention imposed by the tools he was using.

Whatever the reason, the relatively limited number of channels and the structural requirements of music tend to make the channel reservations follow certain patterns. There are typically three drum channels (bass drum, snare drum, and various cymbals) one bass channel, three harmony channels, and one lead channel. Some songs use a dual-channel lead and sacrifice one of the harmony channels to get it.

There are no apparent rules that dictate how channels and their instruments are ordered, other than that the assignments generally don’t change mid-song.

Ⅰ-Ⅰ-Ⅰ-Ⅰ, Ⅳ-Ⅳ-Ⅰ-Ⅰ, Ⅴ-Ⅳ-Ⅰ-Ⅰ.

A great many Bobby Prince compositions follow a twelve-bar blues progression, built on three chords that change in a repeating pattern every twelve measures of the song. The textbook example of this is the title screen music, a rendition of “Tush” by ZZ Top. Once you train yourself to hear it, you’ll find it all over his work from Commander Keen to Duke Nukem 3D.

The Id Engine Sound Manager

The credits of the game include “Music Routines by Id Software” near the bottom of the list, and Id was known for open-sourcing its game code after it was no longer cutting edge. Doing a bit of digging, I was able to trace the lineage of their AdLib code and determine that the version used in this game came from a library file called the “Sound Manager v1.1d1” from Catacomb 3-D, a predecessor to Wolfenstein 3D that Id released in November 1991.

The AdLib code in Cosmo is essentially identical to that in Catacomb 3-D, with only a few modifications and glue code to make it work in this game’s context. Based on the way it was compiled into the final executable, it is almost certain that Todd Replogle had access to the C source and inserted it into the code he was writing. (Other techniques, like sharing a compiled OBJ file and linking it in later, would’ve added additional code segments and other tell-tale evidence which did not occur here.)

id’s Sound Manager was written by Jason Blochowiak, who is also credited with creating the IMF file format the music is encoded in. It was expanded greatly by the time Wolfenstein 3D was released, but as of Catacomb 3-D, the only output types implemented were the PC speaker sound effects (which Cosmo did not use) and AdLib/Sound Blaster music. There was preliminary code to support the Disney Sound Source (a relatively primitive sound effect device) and structures for fine AdLib music control supporting features beyond “play this data blob” and “stop playing it,” but it was not usable at the time of release.

In this document, I will try to straddle the line between how the Sound Manager code was written and how the functions in Cosmo actually work.

SetPIT0Value()

The SetPIT0Value() function configures channel 0 of the system’s Programmable Interval Timer (PIT) with the provided counter value. This counter value can be thought of as a divisor – the larger the value, the longer the counter must run during each timing period, and the slower the resulting timer frequency. The PIT channels count in descending order at a constant rate of 105 ⁄ 88 MHz or 1,193,181.81 Hz, firing one period of output each time the counter reaches zero, thus the resulting timer frequency for an arbitrary value can be determined by f = 1,193,181.81 ⁄ value. Each time this timer fires, interrupt vector 8 (also known as IRQ 0) is raised to the processor.

This function is basically identical to SDL_SetTimer0()1 from Id Software’s Sound Manager as used in Catacomb 3-D.

void SetPIT0Value(word value)

{

outportb(0x0043, 0x36);

The function begins with a call to outportb() to write a byte to I/O port 43h, which is the command register on the system’s Programmable Interval Timer. The value written (36h) has the following interpretation:

| Bit Pattern (= 36h) | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 00xxxxxx | Select timer channel 0 |

| xx11xxxx | Access Mode: “Low byte, followed by high byte” |

| xxxx011x | Mode 3: Square wave generator |

| xxxxxxx0 | 16-bit binary counting mode |

This sets timer channel 0 to a reasonable state: It will output a square wave having a 50/50 duty cycle while counting in binary. The “access mode” configures how the 16-bit counter value will be broken into 8-bit chunks when it is next rewritten.

outportb(0x0040, value);

outportb(0x0040, value >> 8);

pit0Value = value;

}

The outportb() to I/O port 40h (timer channel 0’s data port) programs the new counter value into the PIT, following the convention agreed on in the “access mode” above. The low byte of value is written first, followed by the high byte. Whenever timer channel 0’s counter reaches zero, this becomes the value that will be reloaded into the counter.

Lastly, the configured counter value is stashed in pit0Value for later use.

SetInterruptRate()

The SetInterruptRate() function configures channel 0 of the system’s Programmable Interval Timer (PIT) with an interrupts-per-second value specified by ints_second. This is essentially a wrapper around SetPIT0Value() that abstracts the timer’s count rate away from the calling code.

As a consequence of how the Programmable Interval Timer channels are wired to the Programmable Interrupt Controller on the IBM PC, the value in ints_second becomes the number of times interrupt vector 8 fires each second.

This function is basically identical to SDL_SetIntsPerSec()2 from Id Software’s Sound Manager as used in Catacomb 3-D.

void SetInterruptRate(word ints_second)

{

SetPIT0Value((word)(1192030L / ints_second));

}

There’s not much to explain here that wasn’t already explained in SetPIT0Value(). The only curiosity is the use of the long value 1,192,030 Hz as the dividend in the calculation. As long established, all of the PIT channels run at one-twelfth of the NTSC 315 ⁄ 22 MHz rate, so the expected value here should be rounded to 1,193,182 Hz instead. The difference in rates is 966 parts per million (PPM), which is roughly the equivalent of drifting one second every 15 minutes. Compared to even the cheapest wall clocks available, this accuracy is dismal.

I don’t know and can’t explain why this value was used. Assuming the 14.3 MHz crystals are true to their markings, this value is simply wrong. Regardless, the value survived into Wolfenstein 3-D and later games by Apogee Software and 3D Realms – Jim Dosé’s TS_SetTimer() function in both Rise of the Triad3 and Duke Nukem 3D4 have identical values in their equivalent functions. I’m thinking perhaps the value was published inaccurately in some seminal text on PC systems programming that these developers consulted – if you have any insights on this, please let me know!

Quake5 was quite a bit better at this, but still about 15 PPM off.

ProfileCPUService()

The ProfileCPUService() function is a small interrupt service routine used to benchmark the timing characteristics of the CPU relative to the system’s Programmable Interval Timer. It really only makes sense in the context of the ProfileCPU() function that installs it.

This function is basically identical to SDL_TimingService()6 from Id Software’s Sound Manager as used in Catacomb 3-D.

void interrupt ProfileCPUService(void)

{

profCountCPU = _CX;

profCountPIT++;

outportb(0x0020, 0x20);

}

This is an interrupt handler function, designed to be attached to interrupt vector 8 (which is the PIT channel 0 interrupt), which is also known as IRQ 0. Each time the timer channel fires, the value of the CX register is stored in profCountCPU using a Borland-specific language extension, and the profCountPIT value is incremented. Once all the variables have been adjusted, outportb() sends a nonspecific end-of-interrupt message (20h) to the system’s Programmable Interrupt Controller via I/O port 20h. This acknowledges the IRQ and permits it to fire again later.

If the intent of this function is inscrutable, hopefully ProfileCPU() will clear it up.

ProfileCPU()

The ProfileCPU() function measures the execution speed of the CPU relative to the system’s Programmable Interval Timer, and records the number of busy loop iterations the CPU requires to generate various delay times. The computed delay values are stored in wallclock10us, wallclock25us, and wallclock100us. These values should be passed to WaitWallclock() to produce a delay of (approximately) the required length.

This function is basically identical to SDL_InitDelay()7 from Id Software’s Sound Manager as used in Catacomb 3-D.

void ProfileCPU(void)

{

int trial;

word loops_ms;

setvect(8, ProfileCPUService);

SetInterruptRate(1000);

This function begins by setting interrupt vector 8 to a profiling function, ProfileCPUService(). The original interrupt handler is not saved here – that already happened in StartAdLib() immediately before this function was called. SetInterruptRate(1000) sets the effective timer frequency to 1,000 Hz or one interrupt per millisecond.

From this point, the ProfileCPUService() function runs asynchronously 1,000 times per second. Each time it runs, it sets profCountCPU to the current value held in the CX register and increments profCountPIT. The remaining code in this function relies on the external changes to these two variables.

for (trial = 0, loops_ms = 0; trial < 10; trial++) {

_DX = 0;

_CX = 0xffff;

profCountPIT = _CX;

wait4zero:

asm or [profCountPIT],0

asm jnz wait4zero

wait4one:

asm test [profCountPIT],1

asm jnz done

asm loop wait4one

done:

if (0xffff - profCountCPU > loops_ms) {

loops_ms = 0xffff - profCountCPU;

}

}

This is the measurement loop. trial is the iteration control value that causes the loop to run ten times. loops_ms starts at 0, and eventually becomes the sole output of the loop. The main body of the loop contains a bunch of inline assembly and Borland register keywords.

The DX register is set to zero, which doesn’t appear to be a significant assignment – nothing reads this value and it does not influence the behavior of any of the subsequent instructions. CX is set to FFFFh, which should be interpreted as the value 65,535. profCountPIT is also set to the FFFFh value held in CX, but in this context it could be more naturally thought of as the number -1.

A busy loop is entered next. As long as profCountPIT is not 0, jump back to the wait4zero: label and try again. We just set profCountPIT to -1, so this loop will spin until the timer interrupt fires and increments profCountPIT to 0. As soon as that happens, execution moves onto the next test.

Another busy loop occurs. As long as profCountPIT is not 1, loop back to the wait4one: label and try again. We know that profCountPIT just became 0 in the previous loop; that’s what permitted it to enter the current loop. The only way for it to become 1 is to wait until the timer interrupt fires again. The use of loop is clever – each time the loop instruction executes, it implicitly decrements the CX register. (If CX decrements to zero, loop will terminate, but if that happens here the CPU is running wicked fast and the whole profiling methodology becomes invalid.)

Once the timer fires again and profCountPIT increments to 1, the jump to the done: label is taken and execution moves on. But something else has occurred: The timer interrupt handler copies the value in CX to profCountCPU each time it runs. Since CX holds an indication of how many times the busy loop ran, profCountCPU holds this value now too.

More concretely, the value FFFFh - profCountCPU is the number of times the second busy loop ran, and the second busy loop is tightly governed by two consecutive ticks of a 1,000 Hz clock. Therefore FFFFh - profCountCPU is the number of busy loop iterations that occurred in 1/1,000th of a second (one millisecond). If the most recently measured value is larger than loops_ms, that becomes its new value. The highest (i.e. fastest-performing) value for loops_ms after ten trials is the final result.

loops_ms += loops_ms / 2;

wallclock10us = loops_ms / (1000 / 10);

wallclock25us = loops_ms / (1000 / 25);

wallclock100us = loops_ms / (1000 / 100);

More optimism occurs, and loops_ms is set to 150% of its observed value. From here, it is scaled into three timing variables: wallclock10us is the calculated number of busy loop iterations the CPU can perform in 10 microseconds (µs). wallclock25us and wallclock100us follow the pattern, calculating values for 25 µs and 100 µs respectively.

SetPIT0Value(0);

setvect(8, savedInt8);

}

The function ends with some cleanup. SetPIT0Value(0) sets the timer count value back to 65,536, restoring the PC’s default 18.2 Hz timer rate. setvect() reinstalls the function saved in savedInt8 to interrupt vector 8, returning the timer to the same configuration it was in when this function was entered.

WaitWallclock()

The WaitWallclock() function creates an artificial delay using a CPU busy loop, controlled by the iteration count specified in loops.

This function is basically identical to SDL_Delay()8 from Id Software’s Sound Manager as used in Catacomb 3-D.

void WaitWallclock(word loops)

{

if (loops == 0) return;

_CX = loops;

The function begins with a quick sanity check: If the value requested in loops is zero, no delay is appropriate and the function should return immediately. (If allowed to run anyway, the 16-bit nature of the below loop instruction would actually run for 65,536 iterations, which is not desirable at all.)

The value in loops is copied into the CPU’s CX register, which sets up the subsequent loop.

wait:

asm test [profCountPIT],0

asm jnz done

asm loop wait

done:

;

}

This assembly code looks both strange and familiar; it exactly matches the structure of a loop in the ProfileCPU() function. This is the intent, as we need to make sure that the delay loop is running the exact same instructions and taking the same number of CPU cycles as the calibration loop did.

profCountPIT was abandoned after ProfileCPU() finished executing. It holds some nonzero number, most likely 1, and it doesn’t matter. A test instruction between anything and zero always returns zero, so the jnz jump never occurs.

The loop instruction is doing all the work here. Each time it runs, it decrements CX and, if CX is not zero, it jumps back to the wait: label. The end effect is that the busy loop runs the number of times the caller requested it to, performing no other useful work.

The rest of the function is simply syntactic ceremony to appease the compiler and maintain timing parity.

SetAdLibRegister()

The SetAdLibRegister() function writes one data byte to the AdLib register at address addr, assuming the hardware is present at the standard I/O ports.

This function is basically identical to alOut()9 from Id Software’s Sound Manager as used in Catacomb 3-D.

void SetAdLibRegister(byte addr, byte data)

{

asm pushf

disable();

This function performs some tight timing operations, so it’s necessary to suspend interrupt processing while it runs. The assembly instruction pushf pushes the current state of the CPU’s FLAGS register (most importantly the Interrupt Flag) onto the stack. disable() then turns interrupts off. From this point forward, the code running here has exclusive control of the CPU.

asm mov dx,0x0388

asm mov al,[addr]

asm out dx,al

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

The out instruction sends the value in addr to I/O port address 388h, which is the address register for the AdLib. The temporary involvement of the DX and AL registers is simply a constraint of the x86 instruction set.

The six in instructions repeatedly read the AdLib’s status register at I/O port address 388h into the AL register. The actual value read is irrelevant; the OPL2 chip in the AdLib requires recovery time of about 3.4 µs after writing to the address register before another write can occur, and these instructions provide that delay.

Cycle Pincher

According to the OPL2 docs, the register address latches its value, meaning that if the programmer intends to perform multiple writes to the same register, it is not necessary to re-send the address byte. The AdLib’s design doesn’t include anything that would obviously prevent this from working, so it might have been possible to redesign things to save a few cycles if it was known ahead of time that multiple writes to the same register were planned.

Is the added complexity to do that worth it? Eh, maybe not.

asm mov dx,0x0389

asm mov al,[data]

asm out dx,al

asm popf

Another out instruction follows, this time sending the value in data to I/O port address 389h, which is the data register for the AdLib. The popf instruction pops the most recently pushed value off the stack and installs it into the CPU’s FLAGS register. This restores the flags to the state they were in when pushf was executed earlier, which also has the effect of restoring the Interrupt Flag to the state it was in before.

asm mov dx,0x0388

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

asm in al,dx

}

That’s 35 ins from the AdLib status register at I/O port address 388h, with the returned values in AL being ignored, generating the 23.5 µs recovery time required by the OPL2 chip. Interrupts are enabled here, so this code could very well take longer to execute due to those interruptions, but the OPL2 is guaranteed to have recovered from the data write by the time this function returns.

Math Hat

It’s not readily apparent how the value of 35

ins was selected to delay for 23.5 µs, or how sixins earlier achieved 3.4 µs. The speed of theininstruction is governed by the bus frequency, not the CPU frequency (although historically they both ran at the same speed until CPUs in PC clones became too fast). The highest frequency that any AT/ISA bus is supposed to go is 8 MHz. My best guess is that these figures were based around an 8 MHz bus that takes 5 clock cycles to write each I/O byte.The math suggests that it should actually need 38

ininstructions to generate the required delay instead of 35, but this code has been working for over thirty years and I’m in no position to second-guess it.

Based on some commented-out blocks in the original code,9 it appears the wallclock10us delay was originally intended to produce the address write delay, and wallclock25us was designed for the data write delay. Evidently that approach was abandoned in favor of just whacking the bus a fixed number of times.

AdLibService()