Backdrop Initialization Functions

This game was unusual by early 1990s PC standards because it provided two-layer parallax scrolling during gameplay. Parallax is achieved by drawing multiple layers of screen content that move at different speeds relative to each other, producing an effect that makes the viewer believe that some areas of the map are closer since they scroll faster on the screen. The foreground layer of this game contains basically all of the game content (the map tiles, the player, enemies, decorations, effects, and so on) while the background layer shows a repeating backdrop image. The backdrop layer shows through any area of the map that is not covered by content on the foreground layer – it essentially represents the “air” of the map.

Backdrops can be configured by the map author to scroll horizontally, vertically, or in both directions. Regardless of the movement axis, the backdrop layer scrolls at exactly half the speed of the foreground layer.

This Sounds Extremely Greek

Parallax is an effect where two stationary objects appear to move relative to each other due to the viewer moving. The simplest real-world demonstration would be to look out the side window of a moving vehicle while passing some sparse trees. The closest trees appear to move past the window faster than the farther ones, while the farthest visible things (e.g. clouds and the horizon) don’t seem to move much at all.

Any three-dimensional game with accurate perspective rendering will produce parallax-type effects automatically, but two-dimensional games have to fake it by drawing multiple graphical layers that scroll at different speeds relative to each other. In this game, everything moves and scrolls in eight-pixel increments (due to the way the EGA memory is accessed), but the backdrops scroll in four-pixel increments. This makes the backdrop scroll at half the speed of everything else, and produces an effect where the viewer could plausibly believe that the backdrop was some distance in back of the game world and adding a sense of depth.

We’ve all got our reasons.

This parallax scrolling effect was uncommon in PC games at the time, and the fact that this was able to perform acceptably on a 286 processor was a technical triumph. Most games up until this point drew the map as one solid layer, sometimes (in the case of the first Duke Nukem game) showing a fixed background tile in locations where the map had a transparent window. These all complied with the eight-pixel alignment requirement of the EGA hardware.

Even Commander Keen, which was praised for its smooth sub-tile scrolling, still used an eight-pixel grid internally and invoked some EGA trickery to move the starting position of the entire screen buffer to produce its scrolling effect. That technology only worked if the screen scrolled as one monolithic unit, which is something you’ll notice in Keen’s level designs and gameplay. Cosmo-style parallax would not have been possible in Keen’s game engine.

Incidentally, the desire to understand these parallax scrolling backdrops was what originally inspired me to start disassembling the game, which ultimately led to the creation of Cosmore and then this website.

Many game consoles of the era had dedicated hardware to do layered parallax effects, but the PC offered nothing to help with this endeavor. The programmer had to figure out how to draw everything, then jam it down a one-byte wide memory window to the video hardware.

It’s Harder Than It Seems

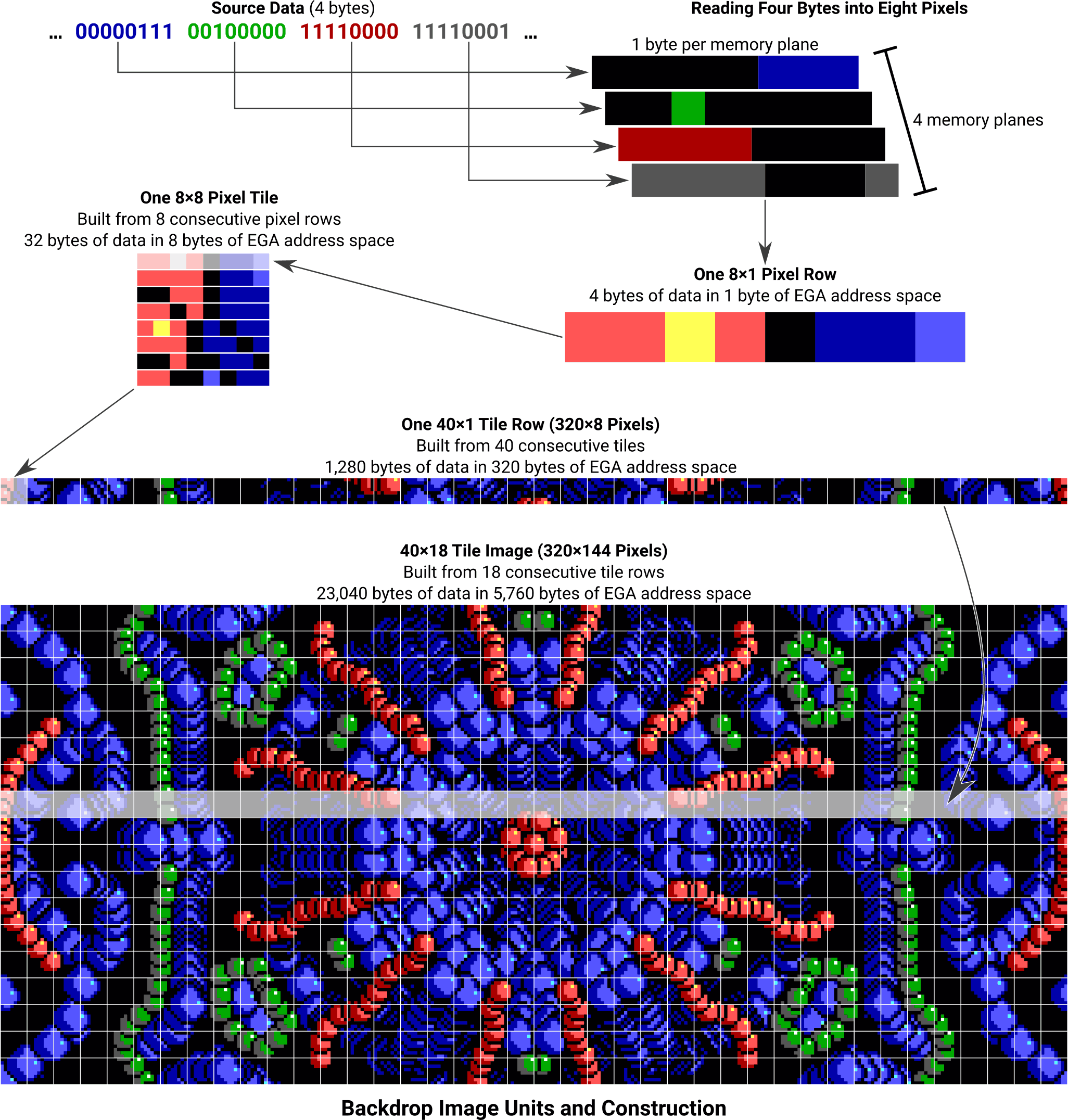

Every graphical element of the game is aligned to an 8 × 8 pixel grid on the screen. Each 8 × 8 pixel region is called a tile. These screen tiles always begin on an eight-pixel boundary in both the horizontal and vertical directions. This applies to everything the game draws – sprites, map tiles, status bar elements, and the backdrop images. This requirement comes from certain aspects of the EGA memory layout.

Very briefly, the EGA memory is split into four planes, with each plane storing one-quarter of the color information for the screen. Within a single plane, each bit of video memory represents one screen pixel (which can be either on or off), thus the combination of the four planes allows for (24) sixteen colors at each pixel position. With this one bit/one pixel mapping, an eight-bit byte holds data for eight consecutive pixels. The eight-pixel tile width is a consequence of memory addresses being aligned to an eight-bit byte. Vertically, there are no such alignment concerns and it’s mainly a matter of preference how tall a tile should be. The designers of this game chose eight pixels in this dimension as well.

Data is written from the CPU to the EGA memory using byte-wide mov instructions, which intrinsically locks the starting position of each write to an eight-pixel boundary and modifies eight horizontal pixels at that position by default. A naïve attempt to draw at an unaligned position on the screen would require reading two bytes from the EGA memory (since the write will in essence “straddle” two consecutive bytes), modify the bit positions being drawn while preserving the bits that are not getting modified, and then write those two bytes back. It’s certainly doable, but it is a tremendous amount of effort on a system that is already being taxed to its limits.

Note: In the above example, these reads and writes would need to happen four times, since each memory plane is read and written independently. The programmer selects which planes to read and write by sending I/O writes to the EGA’s onboard registers. See the EGA page for all the gritty details.

This 8 × 8 pixel constraint is not a problem anywhere else in the game. The maps, sprites, movement calculations, font – everything – are designed around the 8 × 8 pixel grid. All except for the parallax scrolling backdrops, which require 4 × 4 pixel granularity instead.

Duke Nukem Ⅱ used a similar technique to implement its scrolling backdrops, which is detailed in an excellent blog post1 by lethal_guitar. His post goes into some great details about the performance of different drawing approaches on real vintage hardware.

From Eight to Four and Back

The parallax problem is pretty apparent at this point. We have a backdrop image that is built from 8 × 8 tiles, and we need to draw it onto a screen that is (effectively) only addressable on an eight-pixel boundary, but we need to be able to shift the position of this image in four-pixel increments. On top of that, whatever we do needs to be fast enough to redraw the full screen contents during every frame of gameplay.

The game chooses to solve this problem by loading the backdrop image into memory twice. In the first copy, the backdrop is loaded verbatim. In the second copy, the backdrop is shifted four pixels to the right and all of the tiles are rewritten before they are loaded into the EGA memory. Using this arrangement, the first copy can be used whenever the backdrop is positioned on an “even” pixel position (0, 8, 16, 24….) and the other copy is used for “odd” positions (4, 12, 20, 28…) on the screen. As the backdrop scrolls across the screen, the source memory is continually flipping back and forth between these two copies of the source data to produce the slow scroll.

The game can actually do this twice, for both vertical and horizontal scrolling backdrops. On a map with both horizontal and vertical scrolling enabled, there are four backdrop copies (unmodified, shifted horizontally, shifted vertically, shifted horizontally and vertically).

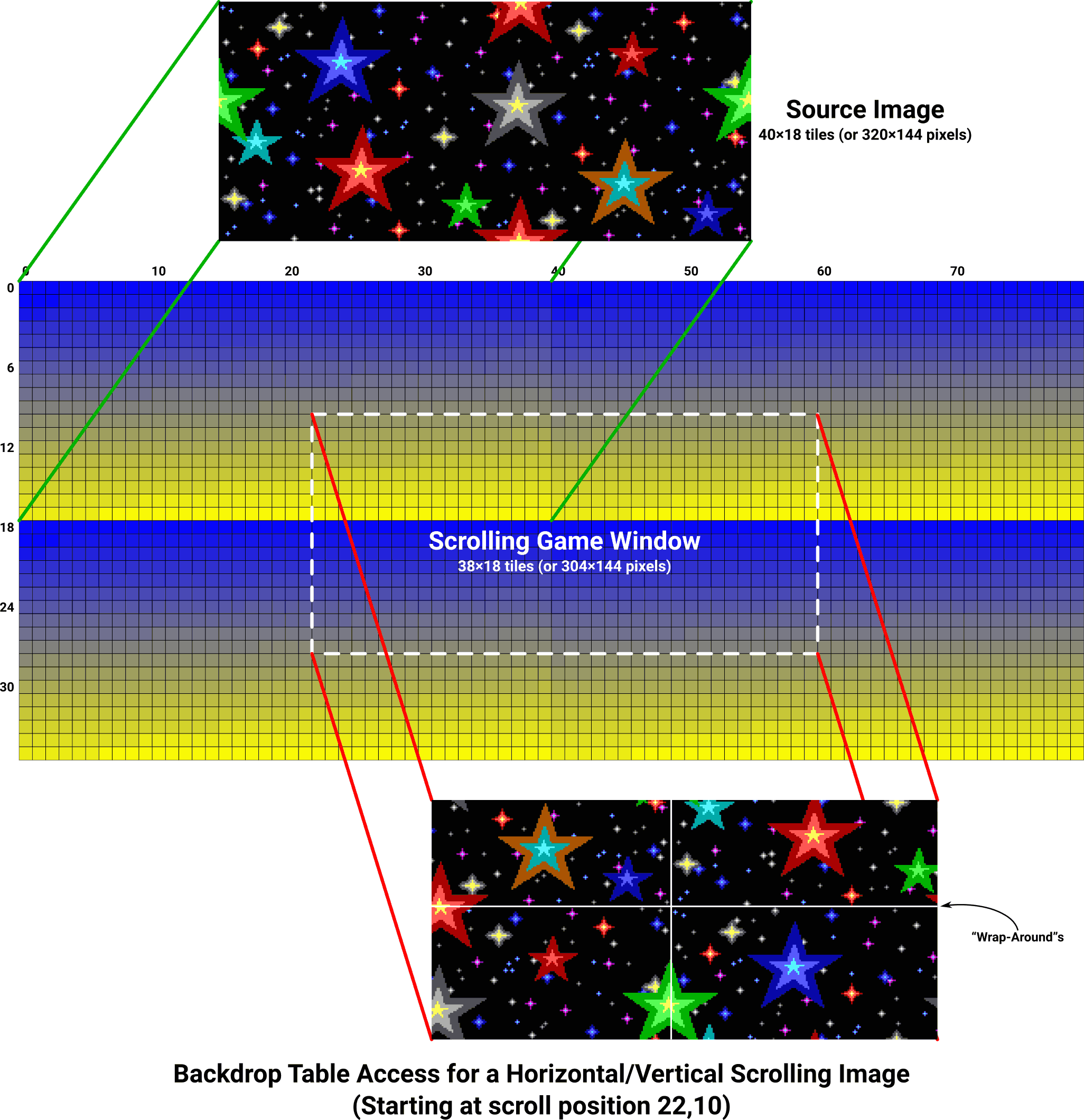

On top of that, the game maintains a lookup table to speed up the calculations that determine where the starting position should be for each scroll position on the map. This also simplifies the “wrap around” calculations that make the backdrop repeat when its edges are reached.

Magic Numbers

Backdrop calculations have a number of fixed constants (the size of a tile, the dimensions of the backdrop, the storage offsets in memory…) and these values need to be combined to produce other derivative values that are used along the way. As these numbers get multiplied and added to each other, the resulting constants get weirder and weirder. This can make it hard to reason about without a cheat sheet to refer back to. This is that cheat sheet:

Or as a table:

| Unit | Size in Pixels | Size in Tiles | EGA Address Space | Physical Memory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pixel | 1 | — | 1 bit | 4 bits |

| Pixel Row | 8×1 (8) | — | 1 byte | 4 bytes |

| Tile | 8×8 (64) | 1 | 8 bytes | 32 bytes |

| Tile Row | 320×8 (2,560) | 40×1 (40) | 320 bytes | 1,280 bytes |

| Image | 320×144 (46,080) | 40×18 (720) | 5,760 bytes | 23,040 bytes |

Note: The physical memory size is always four times the EGA address space due to the four-plane memory access patterns of the EGA hardware. The program must write one byte-width memory address four times, reprogramming the EGA’s color plane selection register between each write, to fill one pixel row of image data.

With that out of the way, let’s tackle the backdrop lookup table first.

Backdrop Table

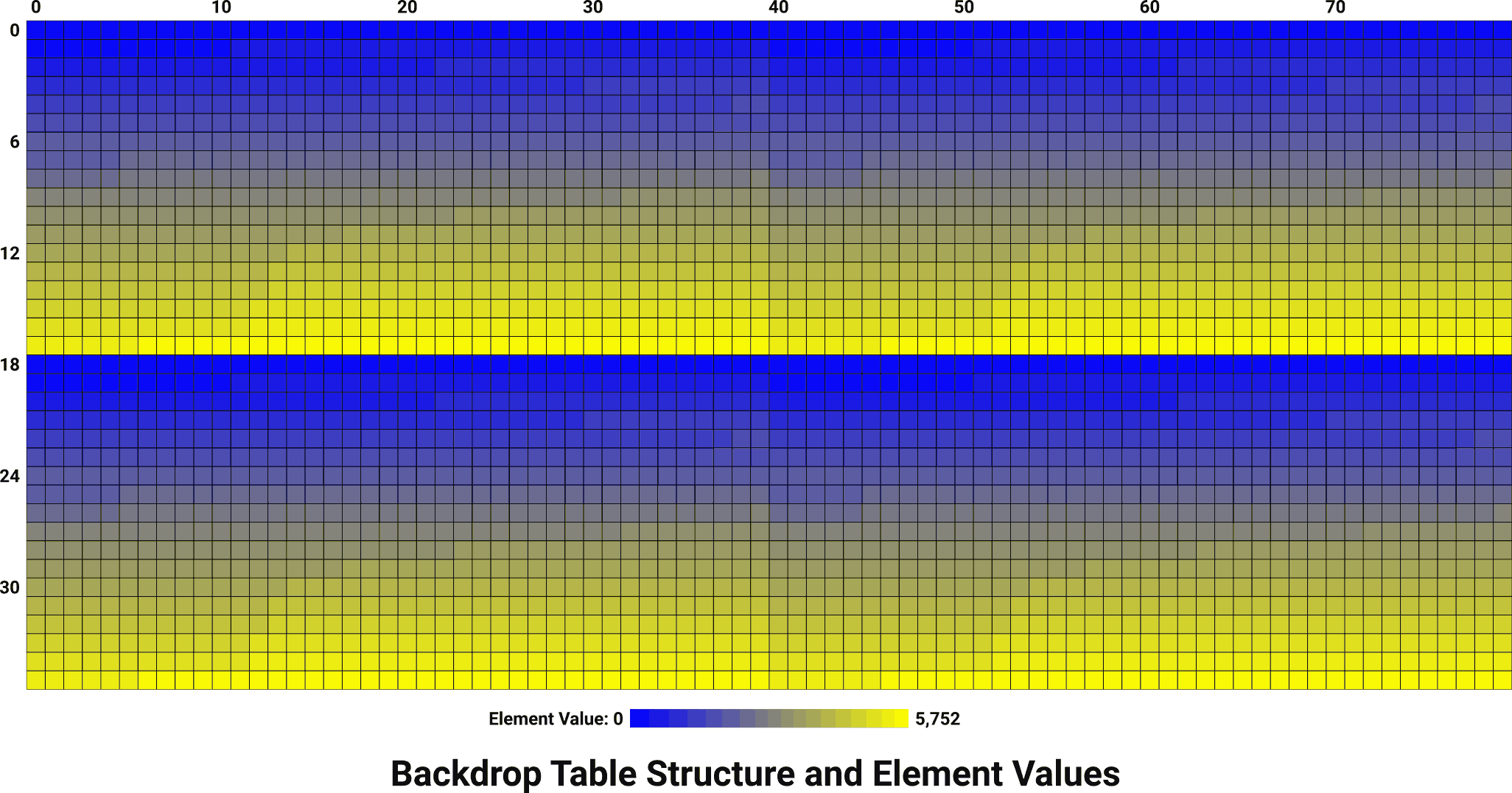

The backdrop table is computed once (when the game is started), and remains in a read-only state until the game exits back to DOS. It is a one-dimensional table of 2,880 elements, but it makes more intuitive sense to think about it as a two-dimensional array in row-major order. When viewed that way, the table is 80 elements wide and 36 elements tall:

The table starts with a value of zero in the first element. At each horizontal step, the value stored at that index increases by eight. When the 40th column is reached, the value is reset back to where it was at the zeroth column, producing a duplicate of the first half of the row. When the 18th row is reached, the value resets to zero and the whole pattern repeats. This produces a “tiled” sequence, occurring twice in the horizontal direction and twice in the vertical. Four copies of a backdrop image (40 × 18 tiles) can fit into this table exactly, tiled in a rectangular arrangement. The points where the table values have a discontinuity are the locations where one copy of the image ends and the next begins, producing a visual wraparound.

When the backdrop is being drawn, this table does two jobs simultaneously. Firstly, it translates an arbitrary (X, Y) tile coordinate pair into an EGA address offset that the game can use to rapidly locate the image data for that tile in EGA memory. Secondly, it takes care of wraparound behavior – as long as the starting tile of a backdrop is located in the conceptual top-left quadrant of the table, it cannot run off either the right or bottom edges – the scrolling game window is simply not large enough for that many drawing iterations to occur. It will, however, frequently run into one of the other three quadrants of the table. When this happens, the jump in offset will “wrap around” and start reading at the opposite edge of the source image.

As long as a backdrop image is crafted to tile in the chosen direction(s), this is visually seamless.

Image Loading and Preparation

The backdrop images in the group files are each built from a sequence of solid tiles stored in row-major order. When the tiles are laid out left-to-right, top-to-bottom, the image is drawn. This is an acceptable format when the backdrop falls exactly on the 8 × 8 grid imposed by the EGA hardware, but more must be done to make it work on the finer 4 × 4 grid that parallax scrolling requires. Additionally, the solid tile drawing routine (DrawSolidTile()) requires the source image data to be stored in EGA memory before it can be drawn.

When a new backdrop needs to be loaded, both of these tasks are done in a single operation. Either one, two, or four copies of the backdrop are installed into the EGA memory, with the additional copies holding four-pixel shifted versions of the image.

To shift a backdrop horizontally, the source backdrop is traversed one pixel row at a time. All of the bits in each color plane are shifted to the left four positions – the most significant bits on right-hand tiles become the least significant bits on the tiles to their immediate left, and the least significants they displace become the new most significant bits. Eventually the four bits that shift off the far left edge’s most significant bits are placed back into the least significant bits on the right side of the image.

for (word tilerow = 0; tilerow < BACKDROP_SIZE; tilerow += 1280) {

for (word i = 0; i < 1280; i++) {

*(dest + tilerow + i) =

/* Left half of tile gets right half of the same tile */

(*(src + tilerow + i) << 4) |

/* Right half of tile gets left half of *subsequent* tile */

(*(src + tilerow + ((i + 32) % 1280)) >> 4);

}

}

This is not the implementation used by the game (sigh) but it demonstrates the principle. The entire 23,040-byte (BACKDROP_SIZE) image is traversed in 1,280-byte chunks, with each chunk representing one tile row. Within each chunk, the individual bytes are modified by bit-shifting the least significant bits left four positions, and filling the newly-created space with the most significant bits from the pixel row immediately to the right, 32 bytes higher in memory. The % 1280 covers wraparound, which will make the rightmost gaps pull from the leftmost pixels of the same row. It is not necessary to keep track of color planes when doing any of this; i can point to data from any color plane and i + 32 will always refer to data in the same plane.

Vertical shifts are slightly simpler because we do not need to operate on sub-byte data. The smallest unit involved is a half-tile, which is 16 bytes in memory. Within each tile, the data needs to be shifted toward lower addresses by 16 bytes, with the space being filled by the data shifted out of the tile one row higher in memory. The data shifted out of the topmost tile shifts into the bottom of the final tile row.

for (word tile = 0; tile < BACKDROP_SIZE; tile += 32) {

for (word i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

/* Top half of tile gets bottom half of the same tile */

*(dest + tile + i) = *(src + tile + i + 16);

/* Bottom half of tile gets top half of *subsequent* tile */

*(dest + tile + i + 16) =

*(src + ((tile + i + 1280) % BACKDROP_SIZE));

}

}

This is similar to the horizontal version except now we operate on 32-byte chunks, each representing one tile in the image. Within each tile, the top pixels (lower addressed memory) receive their contents from the bottom pixels (higher addressed memory) in the same tile, while the bottom pixels get it from the top pixels of the subsequent tile. Each tile contains 32 bytes of data, so the calculations involving “16” produce half-tile distances. The addition of 1,280 skips to the tile immediately below the one being filled, and % BACKDROP_SIZE covers wraparound back to the topmost row of tiles. Color planes are not a concern here either; i and the constants added to it will always locate the correct plane.

There are four possible combinations of shifted backdrops: original, horizontal-shifted, vertical-shifted, and vertical-plus-horizontal-shifted. These four combinations are installed sequentially (in that order) in the EGA memory once these shifted variants are built. If either of the scrolling modes are disabled for a particular map, the EGA memory is still reserved for that backdrop variant but it will contain leftover garbage data.

Backdrop Display

With the backdrop table and variants loaded into system and EGA memory, respectively, the work of drawing the scrolling backdrop to the screen is much less convoluted. If the game window is scrolled to an odd X position, the source backdrop is the version that has been shifted horizontally; otherwise the original (unmodified) version is selected. Similarly, depending on the even/odd state of the Y position, the appropriate vertical variant is chosen. As the game window scrolls, the source image data switches between up to four different versions of the backdrop to provide appropriately-shifted data.

The starting tile position within the backdrop data is determined by halving the screen’s scrollX and scrollY, modulo the backdrop image dimensions (40 × 18). This determines which tile of the backdrop image should be in the top-left corner of the screen.

As the game window is drawn, this starting value gets incremented and the resulting value is looked up through the backdrop table to produce an offset into the EGA memory. This locates the appropriate tile data to draw at that position, including any wraparound points that might be encountered.

This is incredibly fast during gameplay since only a small set of division and modulo operations are needed at the start of each frame, while the per-tile drawing only requires a few additions and a table lookup.

InitializeBackdropTable()

The InitializeBackdropTable() function fills the backdropTable[] array with four identical copies of backdrop tile offset data. The table is conceptually arranged as a two-dimensional grid with one copy of the backdrop offset data in each quadrant. See the backdrop table section on this page for a visual representation of this table and its purpose.

void InitializeBackdropTable(void)

{

int x, y;

word offset = 0;

for (y = 0; y < BACKDROP_HEIGHT; y++) {

for (x = 0; x < BACKDROP_WIDTH; x++) {

*(backdropTable + (y * 80) + x) =

*(backdropTable + (y * 80) + x + 40) = offset;

*(backdropTable + (y * 80) + x + 1480) =

*(backdropTable + (y * 80) + x + 1440) = offset;

offset += 8;

}

}

}

This function is structured as a nested pair of for loops. The outer loop iterates y from zero to the bottom row of backdrop tile data (BACKDROP_HEIGHT). Likewise, x iterates over every column of the backdrop tile data (BACKDROP_WIDTH).

The inner body runs a total of 720 times (once per tile position in one backdrop image) but must fill 2,880 table positions. Since the table contains four copies of identical data spread in different locations, these four assignments can be done sequentially inside the loop.

Each assignment uses (y * 80) + x as a base offset, which seeks to a column x plus a number of 80-wide y rows. To this base offset, an additional offset is added to differentiate the four copies:

- 0 (elided) targets the original tile in the upper-left quadrant.

- 40 stays on the same row, but skips the

xvalue 40 columns to access the upper-right quadrant. - 1,440 skips the

yvalue past the first 18 rows (80 × 18) to access the lower-left quadrant. - 1,480 is the combination of 40 plus 1,440, to access the lower-right quadrant.

Each of these offsets is used as an index into the backdropTable[] array, and the current offset value is written to all four locations. At the end of each inner iteration, offset is incremented by eight to skip to the next tile offset value in EGA address space.

Once the backdrop table is constructed, its contents do not need to be refreshed if backdrops (and scroll direction flags) are changed. backdropTable[] effectively contains read-only data.

IsNewBackdrop()

The IsNewBackdrop() function tracks the most recently used backdrop number and horizontal/vertical scroll flags. The scroll flags are read from global variables, but the backdrop number being tested must be passed in backdrop_num. This function returns true if these have changed since the previous call, or false if none of the tracked variables have changed. This is used by InitializeLevel() to avoid a costly call to LoadBackdropData() in cases where the correct data is already in memory.

This helps speed up cases where the level restarts due to the player’s death, or when a new level happens to have the same backdrop settings as the level that just exited.

bbool IsNewBackdrop(word backdrop_num)

{

static word lastnum = WORD_MAX;

static word lasth = WORD_MAX;

static word lastv = WORD_MAX;

if (

backdrop_num != lastnum ||

hasHScrollBackdrop != lasth ||

hasVScrollBackdrop != lastv

) {

lastnum = backdrop_num;

lasth = hasHScrollBackdrop;

lastv = hasVScrollBackdrop;

return true;

}

return false;

}

This function sets up three variables (lastnum, lasth, and lastv) to track the most recently-seen backdrop number, horizontal scroll flag, and vertical scroll flag. Since these are declared static inside a function, they retain their values across calls. Each is initially set to the impossible value WORD_MAX to ensure that the first call will always report the backdrop as being new.

If either of the global hasHScrollBackdrop/hasVScrollBackdrop variables or the passed backdrop_num differ compared to the previous call, the updated values are recorded locally and the function returns true to indicate to the caller that the backdrop data in memory is out of date and needs to be regenerated.

Otherwise everything matches, nothing is updated, and the function returns false.

LoadBackdropData()

The LoadBackdropData() function reads backdrop data from the passed group file entry_name and installs it into the appropriate location in the EGA memory. If horizontal and/or vertical scrolling is enabled in the map variables, additional copies are loaded into the EGA memory to facilitate sub-tile parallax scrolling. A scratch buffer is required, which must be large enough to hold two complete copies of backdrop data plus an additional 640 bytes.

void LoadBackdropData(char *entry_name, byte *scratch)

{

FILE *fp = GroupEntryFp(entry_name);

The provided entry_name is passed to GroupEntryFp(), which locates the correct backdrop data in the group files and returns a file stream pointer in fp.

EGA_MODE_DEFAULT();

EGA_BIT_MASK_DEFAULT();

miscDataContents = IMAGE_NONE;

The EGA_MODE_DEFAULT() macro resets the EGA read/write mode registers to their default state, while EGA_BIT_MASK_DEFAULT() clears any transparency state that may have been left over from a previous masked drawing operation. The combined effect of these two settings ensures that all bits written to the EGA memory will be stored without modification.

Subsequent operations in this function may use the miscData buffer, invalidating any contents it holds. This function unconditionally sets the miscDataContents caching flag to IMAGE_NONE, indicating that the contents of this memory cannot be subsequently used by (e.g.) DrawFullscreenImage() without being reloaded.

fread(scratch, BACKDROP_SIZE, 1, fp);

CopyTilesToEGA(scratch, BACKDROP_SIZE_EGA_MEM, EGA_OFFSET_BDROP_EVEN);

fread() reads from fp into scratch, loading one record of BACKDROP_SIZE bytes. CopyTilesToEGA() then copies that same data from scratch into the EGA_OFFSET_BDROP_EVEN EGA memory region. Since the destination of this write resides in four-plane EGA memory, only a quarter of the address space is necessary. This is why BACKDROP_SIZE_EGA_MEM is one-fourth the size of the source BACKDROP_SIZE.

At the end of these function calls, there are two key changes in state:

scratchpoints to a copy of the unmodified backdrop image as it was read from the disk.EGA_OFFSET_BDROP_EVENcontains a copy of the same unmodified backdrop image, installed in the EGA memory.

In a hypothetical game map with no scrolling enabled, this single copy of the backdrop image is all that would be required during gameplay.

if (hasHScrollBackdrop) {

WrapBackdropHorizontal(scratch, scratch + BACKDROP_SIZE);

CopyTilesToEGA(

scratch + BACKDROP_SIZE, BACKDROP_SIZE_EGA_MEM,

EGA_OFFSET_BDROP_ODD_X

);

}

If the map has horizontal backdrop scrolling enabled, hasHScrollBackdrop will hold a true value and this block will execute.

WrapBackdropHorizontal() reads the unmodified backdrop data from scratch, and writes a horizontally shifted/wrapped copy of the backdrop to scratch + BACKDROP_SIZE. When this returns, the scratch buffer contains this data:

| Symbol | Offset (Bytes) | Size (Bytes) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

scratch | 0 | 23,040 | Original backdrop image. |

scratch + BACKDROP_SIZE | 23,040 | 23,040 | Backdrop image shifted four pixels horizontally. |

CopyTilesToEGA() then installs the shifted backdrop image from scratch + BACKDROP_SIZE into the EGA_OFFSET_BDROP_ODD_X EGA memory region. As with the original backdrop, the size of the write to EGA memory is BACKDROP_SIZE_EGA_MEM bytes.

At the end of this block, there are two more changes in state:

scratch +BACKDROP_SIZEpoints to a horizontally shifted copy of the background image.EGA_OFFSET_BDROP_ODD_Xcontains a copy of this horizontally shifted backdrop image, installed in the EGA memory.

if (hasVScrollBackdrop) {

WrapBackdropVertical(

scratch, miscData + 5000, scratch + (2 * BACKDROP_SIZE)

);

CopyTilesToEGA(

miscData + 5000, BACKDROP_SIZE_EGA_MEM, EGA_OFFSET_BDROP_ODD_Y

);

Similarly, if the map has vertical backdrop scrolling enabled, hasVScrollBackdrop will hold a true value and this block will execute.

WrapBackdropHorizontal() reads the unmodified backdrop data from scratch, and writes a vertically shifted/wrapped copy of the backdrop to miscData + 5000 – this is a free-for-all buffer used for a variety of unrelated things. Of particular interest here is demo data, which occupies the first 5,000 bytes of this memory area. Since it’s typical for demos to span several levels, requiring backdrop changes in between, it makes sense that the demo data would need to persist in memory for longer than backdrop scratch storage would. For this reason, 5,000 bytes are skipped during every access to miscData here, leaving demo data undisturbed.

On top of that, WrapBackdropVertical() requires a separate scratch area to wrap pixels from the top of the image around to the bottom. It needs 640 bytes of space to do this, and even though miscData has enough unused space to accommodate that, the game chooses to use the end of scratch for this temporary storage.

Once wrapping is complete, the scratch buffer contains this data:

| Symbol | Offset (Bytes) | Size (Bytes) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

scratch | 0 | 23,040 | Original backdrop image. |

scratch + BACKDROP_SIZE | 23,040 | 23,040 | Backdrop image shifted four pixels horizontally. |

scratch + (2 * BACKDROP_SIZE) | 46,080 | 640 | Garbage; 40 half-tiles wrapped by WrapBackdropHorizontal(). |

miscData contains this:

| Symbol | Offset (Bytes) | Size (Bytes) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

miscData | 0 | 5,000 | Demo data, if any is being played back or written. Otherwise garbage. |

miscData + 5000 | 5,000 | 23,040 | Backdrop image shifted four pixels vertically. |

CopyTilesToEGA() then installs the shifted backdrop image from miscData + 5000 into the EGA_OFFSET_BDROP_ODD_Y EGA memory region. As with the previous backdrops, the size of the write to EGA memory is BACKDROP_SIZE_EGA_MEM bytes.

At the end of this block, there is only one significant change in state:

EGA_OFFSET_BDROP_ODD_Ycontains a copy of this vertically shifted backdrop image, installed in the EGA memory.

WrapBackdropVertical(

scratch + BACKDROP_SIZE, miscData + 5000,

scratch + (2 * BACKDROP_SIZE)

);

CopyTilesToEGA(

miscData + 5000, BACKDROP_SIZE_EGA_MEM, EGA_OFFSET_BDROP_ODD_XY

);

}

Still inside the hasVScrollBackdrop condition, another wrap and install operation occurs. This makes the fourth backdrop variant that is shifted horizontally and vertically. To do this, it re-uses the horizontally shifted copy previously stored in scratch + BACKDROP_SIZE.

Note: In cases where

hasHScrollBackdropis false, the horizontal wrapping block will not have run and the source memory here will contain uninitialized garbage data. This garbage data will get wrapped and loaded into EGA memory, but it is never read due tohasHScrollBackdropbeing false when checked later inDrawMapRegion().

This works identically to the previous code, except the source data is pre-shifted in the horizontal direction ( scratch + BACKDROP_SIZE) and the destination is EGA_OFFSET_BDROP_ODD_XY in the EGA memory. By vertically shifting an image that has already been horizontally shifted, an image is produced that is shifted by a half-tile on both axes.

fclose(fp);

}

With no more data to read, the file fp points to is fclose()’d and this function returns.

WrapBackdropHorizontal()

The WrapBackdropHorizontal() function creates a modified copy of the backdrop image pointed to by src and stores it in the location pointed to by dest. The new copy of the image is shifted horizontally toward the left by four pixels, and the four columns of pixels that shift off the left edge are wrapped into the empty space created at the right edge. It is safe for src and dest to point to the same memory, in which case the image will be modified in-place.

The ability to modify images in-place adds a significant amount of complexity, which the game does not actually use. At any given point, there are only four horizontal pixels worth of data being moved, making the algorithm work somewhat like a sliding puzzle game2. It’s not possible to move more than four pixels worth of data in one step without corrupting the final image.

void WrapBackdropHorizontal(byte *src, byte *dest)

{

register word trow, col;

word plane, prow;

byte scratch[4];

This function uses the following local variables:

trow: Holds the physical memory offset to the current tile row being operated on. This steps in 1,280-byte increments over the 18 rows of tiles in the backdrop image.prow: Holds the relative offset to the current pixel row being operated on. This steps in 4-byte increments over the eight pixel rows in a tile. This is added totrowto compute the offset of a specific pixel row in the image data.col: Holds the relative offset to the current tile column being operated on. This steps in 32-byte increments from 0 to 1,280 within a tile row, and is added totrowandprowto produce the offset to a specific tile in the image data.plane: When individual color planes are being operated on, this increments from 0 to 3 to address the data for that specific plane.scratch: This is a four-byte buffer which can temporarily hold the four-plane color data for a single pixel row. This is used to wrap left-hand pixels around to the right-hand edge of the image.

for (trow = 0; trow < BACKDROP_HEIGHT * 1280; trow += 1280) {

for (prow = 0; prow < 8 * 4; prow += 4) {

trow increments over the tile rows of the image (BACKDROP_HEIGHT iterations in 1,280-byte steps), and prow increments over the eight pixel rows inside each row’s tiles. Everything else in this function resides within these loop bodies, and trow and prow are always added together whenever either one subsequently appears. It is conceptually simpler to think of these two loops as iterating over the 144 pixel rows in the image, producing the offsets for the pixels in the leftmost column of tiles during each iteration.

for (plane = 0; plane < 4; plane++) {

*(scratch + plane) = *(src + plane + prow + trow) >> 4;

}

Before doing any substantial modification to the image, we need to temporarily save the leftmost four pixels at the position we’re working on. Once the image content is fully shifted, these displaced pixels will need to be restored on the right side of the image to produce the horizontal wrap.

This loop body runs four times, once for each color plane. The source data on each iteration consists of one byte, representing an 8 × 1 pixel row from the leftmost column of tiles. Ultimately four bytes need to be read from the source data to capture the color information from all four planes.

Each byte read from src is bitwise-shifted to the right by four positions, which achieves two goals: Firstly it discards the right four pixels, which do not need to be wrapped around to the other side. Secondly, it moves the preserved pixels into the right half of the row, which is where they need to be located when restored on the right side of the image. This data is stashed in the local scratch buffer for later use.

for (col = 0; col < BACKDROP_WIDTH * 32; col += 32) {

for (plane = 0; plane < 4; plane++) {

*(dest + col + plane + prow + trow) =

*(src + col + plane + prow + trow) << 4;

}

Next we operate on the remainder of this pixel row, one tile column (col) at a time. At that tile position, for each plane, we read the pixel data from the src image and bitwise-shift it to the left by four positions. This moves the pixels four places to the left, discarding the old left-hand data and shifting zeros (which are visually black) into the right side. This intermediate data is written into the dest image at the same byte offset.

At no point does this lose information – we only displace four pixels per plane during each iteration, and the data in the scratch buffer has freed up enough wiggle room for us to shuffle the data around as long as we don’t disturb more than four pixel positions at a time.

if (col != (BACKDROP_WIDTH - 1) * 32) {

for (plane = 0; plane < 4; plane++) {

*(dest + col + plane + prow + trow) =

*(dest + plane + prow + trow + col) |

(*(src + plane + prow + trow + col + 32) >> 4);

}

}

}

Still inside the col loop, it is time to fill the right half of this pixel row’s data, which currently holds black. This is accomplished by reading the left half from the pixel row immediately to the right, and overlaying it onto the right half of the pixel row being built.

This is wrapped in an if check that passes as long as we are not operating on the rightmost tile column – if we were at the right edge, there is nothing further to the right for us to read. That case is handled later.

Otherwise, we are at a typical column and can simply read from src 32 pixels ahead of where we are writing. This points to the same plane of the same pixel row, but one tile to the right of dest. The read data is shifted to the right by four pixels, which discards the pixels we don’t want to move and places the pixels we do want to move in the correct location within the byte. The left-hand pixels of the source data are black, as are the right-hand pixels in dest. By bitwise-ORing the two together, the two halves are merged into the final value, which is written back to dest.

This process repeats horizontally across the image until the rightmost edge is reached. At that point, the pixels on this line of the image are fully shifted except for a four-pixel black band at the right.

for (plane = 0; plane < 4; plane++) {

*(dest + plane + trow + prow + ((BACKDROP_WIDTH-1) * 32)) |=

*(scratch + plane);

}

}

}

}

This final loop repairs the right edge of the image by unstashing the four pixels (one per color plane) that were removed from the left side of the image. These are stored in the low bits of the scratch buffer. By combining the existing pixels in the rightmost tile columns (located at BACKDROP_WIDTH- 1) with the stashed pixels, the right edge of the image is filled.

Once this is done, the prow and trow loops continue, moving down to the subsequent row of pixels in the image. Once the inner code has run 144 times, every piece of the image will have been touched and the wrap is complete.

WrapBackdropVertical()

The WrapBackdropVertical() function creates a modified copy of the backdrop image pointed to by src and stores it in the location pointed to by dest using a scratch buffer of at least 640 bytes. The new copy of the image is shifted vertically toward the top by four pixels, and the four rows of pixels that shift off the top edge are wrapped into the empty space created at the bottom edge. It is safe for src and dest to point to the same memory, in which case the image will be modified in-place.

As with WrapBackdropHorizontal(), the ability to modify images in-place adds a significant amount of complexity that the game does not actually use. Each major step in the algorithm copies a 320 × 4 strip of pixel data up on the screen, duplicating the strip of pixels below and destroying the content that was previously held in that location. The scratch buffer receives the topmost strip of pixels before they are destroyed, and this data is restored at the bottom of the image at the very end.

void WrapBackdropVertical(byte *src, byte *dest, byte *scratch)

{

register word col, i;

word scratchoffset, offset, row;

This function uses the following local variables:

i: In each placeiappears, it is used as a generic iterator from zero to 15. It is not used in offset calculations; it merely serves to control the number of iterations of a loop body.col: Much likei, this is a loop control variable that ensures the relevant loops run from zero toBACKDROP_WIDTH- 1, over each column of tiles.row: When the image data is being manipulated, this variable tracks the current tile row being operated on. Whenever this value is read within the loop, it is multiplied by 1,280 to scale the tile row number into a pixel row offset in bytes.scratchoffset: This is used as an offset into the data held in thescratchbuffer, which increments by one as this scratch data is written and then read back.offset: This is the main read/write position in the image data. This is incremented by one to read the next byte of pixel data, and intermittently incremented by 16 to skip over the bottom four pixel rows in one tile and advance to the topmost pixel row in the subsequent tile.

scratchoffset = 0;

offset = 0;

for (col = 0; col < BACKDROP_WIDTH; col++) {

for (i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

*(scratch + scratchoffset++) = *(src + offset++);

}

offset += 16;

}

This loop copies the topmost four rows of pixels from the src image into the scratch buffer. In total, 40 half-tiles worth of data are copied here, and stored contiguously in the 640 byte buffer.

Initially, both scratchoffset and offset are zeroed, pointing to the first byte of pixel data in both the source data and the scratch buffer. The outer for loop sets up for BACKDROP_WIDTH iterations, moving col from zero to 39 and representing horizontal steps, one tile wide, across the image’s width. The inner for loop iterates i a total of 16 times, allowing the inner loop body to run once for every byte of data in the top half of the current tile.

Within the loops, a straightforward assignment copies the src data (indexed by offset) into the scratch data (indexed by scratchoffset). Both offset values are incremented as each byte is copied.

For the first 16 assignments, offset and scratchoffset hold identical values. Once the inner loop terminates, half of a tile has been copied into the scratch buffer. offset is then incremented by 16 to skip over the remaining bottom half of data present in this tile, which locates the start of the data in the subsequent tile. From this point on, offset and scratchoffset diverge until the end of the outer loop, at which point offset has scanned over 1,280 bytes of source data but scratchoffset has only reached 640 bytes in size.

With the top half-tile of image data preserved in the scratch buffer, it is safe for the remainder of this function to start overwriting this area with shifted image data.

for (row = 0; row < BACKDROP_HEIGHT; row++) {

offset = 0;

for (col = 0; col < BACKDROP_WIDTH; col++) {

for (i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

*(dest + offset + (row * 1280)) =

*(src + (row * 1280) + offset++ + 16);

}

offset += 16;

}

The outermost for loop increments col from zero to BACKDROP_HEIGHT - 1, targeting each tile row in the image data sequentially. At the start of each column, offset is zeroed to reset the read/write position to the first pixel row in the leftmost tile there.

Inside that, a pair of for loops sets up an iteration over each tile in the row, and each byte of data within the top half of that tile. These loops, and the offset += 16 within them, is structured identically to and works the same as the pair of loops in the scratch preparation that appeared earlier. The net result is that i increments 16 times, then skips ahead 16 bytes, and this pattern repeats for each tile in the row. This produces half-tile-sized copies.

Within the innermost loop body, an assignment copies one byte at a time from the src data into the dest data. Each side of the expression uses (essentially) equivalent calculations: row * 1280 translates the current tile row number into a skip value, while offset targets the individual data bytes within that tile row. The source data is read 16 bytes ahead of the destination data, which has the effect of reading from the bottom half of a tile while writing into the top half of that same tile. This duplicates the bottom half of a tile onto its top half, destroying the content that was there previously.

Note: The construction of this assignment is undefined behavior, as

offsetis incremented on the right-hand side of the expression while it is being read on the left-hand side. The code is written in this way to maintain parity in the compiled code. The desired behavior is foroffsetto be incremented after the entire expression is completed, resulting in the left-hand side using the not-yet-incremented value.

Once a full tile row has been operated on, execution continues to another set of loops.

offset = 0;

for (col = 0; col < BACKDROP_WIDTH; col++) {

for (i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

*(dest + offset + (row * 1280) + 16) =

*(src + (row * 1280) + offset++ + 1280);

}

offset += 16;

}

}

Here we are still inside the outermost row loop, and we now need to rewrite the bottom half of the tile row we just operated on. The structure and behavior of the two for loops here is exactly the same as the previous loop, to the point where their bodies could have been merged together and still work properly.

The assignment is almost the same as well (right down to the admonishment about undefined behavior) but the fixed offsets are different. Here we read the src data 1,280 pixels ahead of where we’re writing, which reads from the top half of the tile directly below the current one. The write position is biased by 16 to direct this data at the bottom half of the tile.

When this assignment is complete, the bottom half of each tile in this row contains a copy of the top half of the tile one row lower in the image. With both half-tiles now written, this tile row is complete and the row loop can move on, repeating the procedure for every tile row in the image.

Note: This code performs an out-of-bounds read on the final tile row, reading garbage data from beyond the conceptual end of the source image. This fills the bottom four rows of pixels in the image with junk, but that doesn’t matter because this data gets replaced by the content that had been stashed in

scratch.

offset = 0;

scratchoffset = 0;

for (col = 0; col < BACKDROP_WIDTH; col++) {

for (i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

*(dest + offset++ + ((BACKDROP_HEIGHT - 1) * 1280) + 16) =

*(scratch + scratchoffset++);

}

offset += 16;

}

}

With the image fully rewritten (except for four pixel rows of gibberish at the bottom of the image) we are ready to “wrap” the data that was removed from the top of the image onto the bottom. This code performs that task, and is exactly the inverse of the first loop that stashed the data into scratch to begin with. The key difference is the offset used for dest, which has a fixed value of ((BACKDROP_HEIGHT - 1) * 1280) + 16 added to it. This shifts the scratch data, which was read relative to the top half of the topmost tile row in the image, to instead be written relative to the bottom half of the bottommost tile row. Aside from this fixed difference in offsets, the write is the inverse of the original read.

When this completes, the bottom of the image no longer contains the garbage it had earlier, and the image has been shifted and wrapped. The data in the scratch buffer is no longer useful and can be overwritten freely.