Keyboard Functions

The keyboard subsystem on IBM computers was surprisingly complicated. This was due in no small part to a number of changes in key layout and function, as well as compatibility requirements between not just the IBM Personal Computer product line, but with the PS/2 and mainframe terminals as well.

The (Relatively) Simple World of the IBM PC/AT

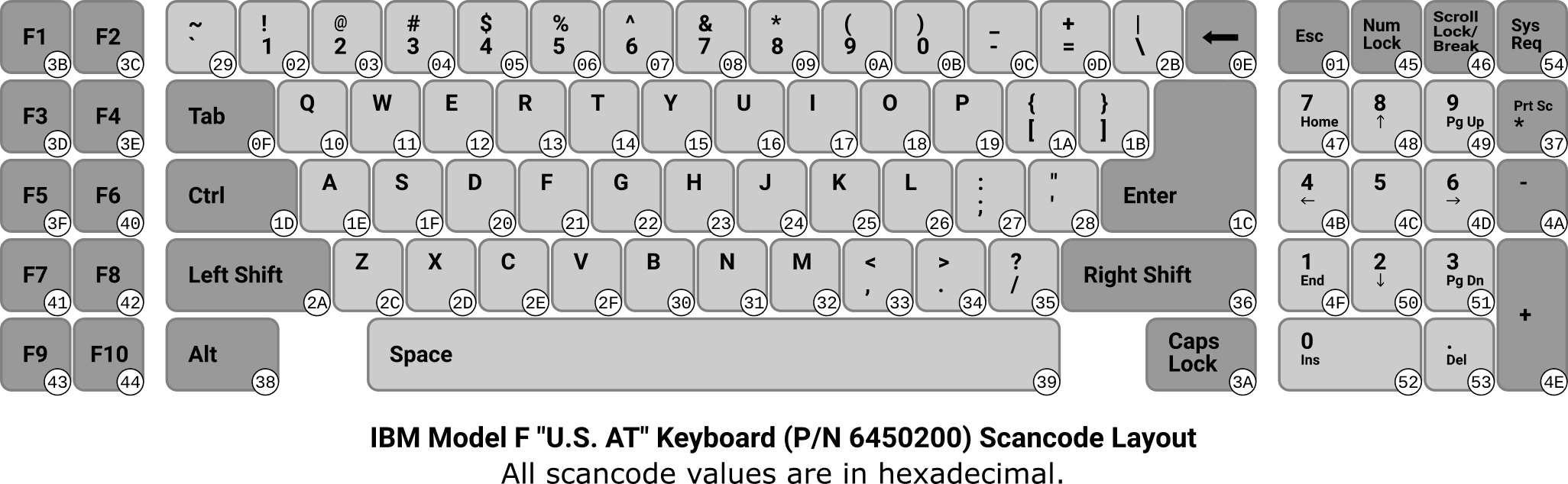

The original IBM PC and XT keyboards were 83-key units. After incorporating feedback from users who were frustrated by the layout, the keys were rearranged for the 84-key keyboard released with the IBM Personal Computer/AT:

The 84th key, added with the release of the AT, is Sys Req, which BIOS responds to by raising interrupt 15h/AH=85h. In terms of key functions, the keyboards for the PC/XT and the AT are otherwise identical – only the physical arrangement of the keys is different. (This also explains the discontinuities and odd arrangement of the scancodes on the AT keyboard; the codes were sequentially ordered on the PC/XT and followed the keys where they moved on the AT.)

The scancode format on these keyboards is drop-dead simple: Whenever a key is pressed, the scancode (one of the numbers in the white bubbles) is generated by circuitry in the keyboard, that value is sent serially over the wire into the system unit, and the keyboard controller captures the data. This “key down” event is sometimes referred to as a make code. When a key is released, the key’s scancode is OR’d with 80h and that value is sent over the wire by the same mechanisms. This is a break code. So pressing A will send the make code 1Eh, and releasing it will send break code 9Eh. Most keys have typematic operation, where holding down a key will type a repeating sequence of that character after a short delay. The delay and repetition is handled by the keyboard itself, and this is expressed to the system by retransmitting the make code at regular intervals for as long as the key is being held.

Scancodes are not directly tied to the actual character being typed – different writing systems can (and did) define their own keycaps and language-appropriate interpretations for each scancode. To keep things simple here, I’m only going to describe things in terms of U.S. English. Substitute your preferred keyboard overlay as desired.

At the protocol level, the PC/XT and AT keyboards are quite different. The PC/XT keyboard sends scancodes over the wire as described in the image above, but the AT keyboard uses an incompatible scancode mapping based on a wildly different 122-key layout (called the “Host Connected Keyboard”) originally designed for IBM terminals. Internally, the AT’s keyboard controller translates these 122-key scancodes into their PC/XT values before doing any further processing to avoid software compatibility problems. The AT keyboard protocol also introduces bidirectional communication, which permits the host system to command the keyboard to do things like like adjust the typematic repeat rate and turn LEDs on and off.

Some third-party keyboards of the era had a configuration switch that allowed the keyboard to be switched from PC/XT to AT mode as needed, and more sophisticated keyboard controllers gained the ability to interrogate the keyboard and “guess” whether it transmits the PC/XT or the AT scancode set.

Why bother?

The prevailing theory is that the AT used this scancode mapping to allow a user to plug a 122-key keyboard into the AT and have it work. If a poll was conducted to find out how many users actually did this, my guess would be “not all that many.”

It’s important to understand that most keys on the keyboard have at least two functions when interpreted by the software running on the computer. There are the obvious examples like the letter keys which typically type lowercase, while holding one of the Shift keys switches them to uppercase. If Caps Lock is on, this behavior is reversed and Shift changes the letters (and only the letters) to their lower case. Shift also changes the number keys into punctuation, and it shifts the characters typed by the punctuation-only keys.

The numeric keypad adheres to similar behavior. With Num Lock off, which was typically the default on older systems, these keys function as cursor control keys: Home/End/Page Up/Page Down/arrows and so forth. By holding Shift, these keys type digits. Num Lock reverses this behavior, causing digits to be typed without Shift being held and cursor movement with Shift.

The * key on the numeric keypad types that character by default, but with Shift held it becomes the “Print Screen” function. (Some programs use Ctrl+* as an alternate function, often to stream text to the printer as it appears on the screen.)

The unlabeled key combination Ctrl+Num Lock serves as the “Pause” function, which causes the BIOS keyboard handler to (intentionally) hang until any key other than Num Lock is pressed. Ctrl+Scroll Lock causes the “Break” action, triggering interrupt 1Bh for software to handle as it sees fit. Do not confuse this with the general concept of a key break scancode – “Break” here means “stop program execution.”

Pressing Ctrl along with the keys for @, A – Z, [, \, ], ^, or _ generates unprintable control bytes in the range 0h–1Fh, respectively. Ctrl+Backspace generates byte 7Fh.

Pressing the Alt key while entering a three-digit decimal number on the numeric keypad allows for arbitrary bytes to be entered by value. And finally, the famous three-finger salute to forcibly reboot the system was actually Ctrl+Alt+Num ., since the only Del key on these keyboard shared a key with that character. Aside from these uses, Alt is not a commonly seen key for system software on these machines.

All of this functionality is implemented in software, and handled at the BIOS level. From the keyboard’s perspective, all it needs to do is send messages as keys are pressed and released ("Left Shift down, S down, S up, Left Shift up…") and the software just sees a stream of finalized characters ("S, c, o, t, t…") and control bytes without much understanding of precisely how the user typed them.

If you thought this was complicated, wait until you see what they did next.

You’re Gonna PS/2 It!

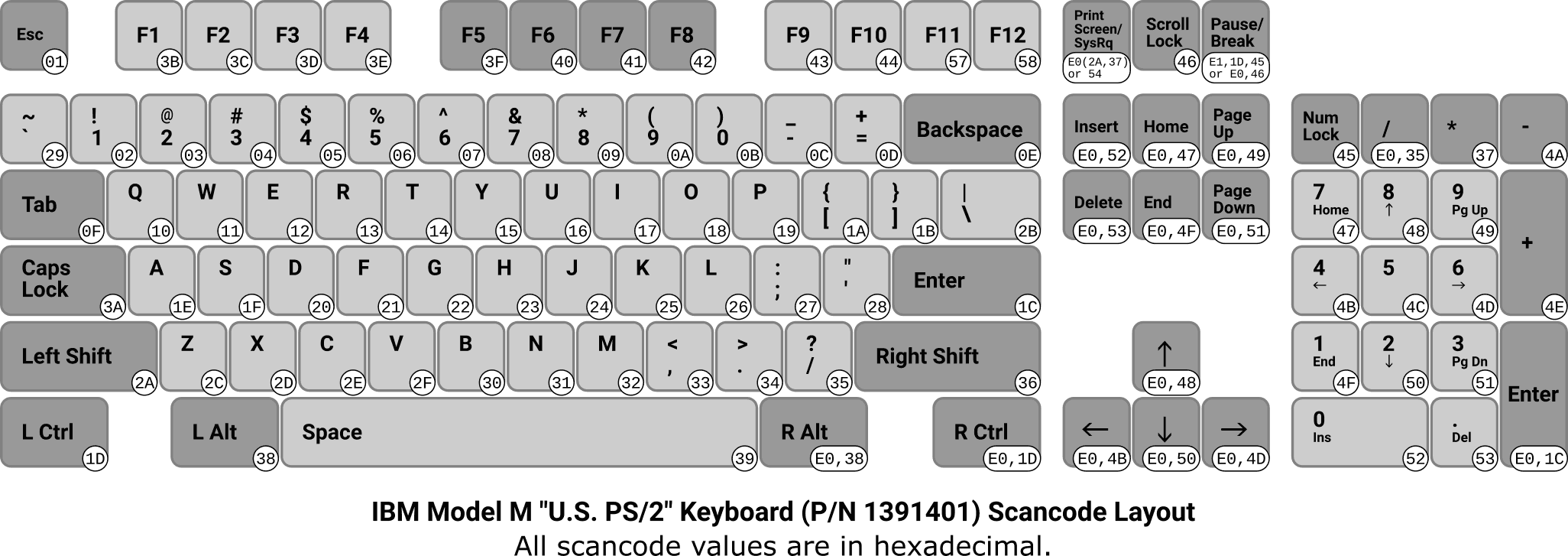

The IBM Personal System/2 (PS/2) increased the number of keys on the keyboard to 101. This keyboard design was an instant hit, and started to see wide adoption across all facets of the PC and compatible market. These keyboards are still being used today.

The designers painted themselves into a bit of a corner with this one. The AT system uses a scancode mapping based around the Host Connected Keyboard’s 122-key layout, which has a whole bunch of keys that the 101-key layout does not have. There was no good way to fit these new keys into the existing encoding scheme in a compatible way without extending it to require multiple bytes for some of the keys. So that’s what they did.

14 of the keys (Right Ctrl, Right Alt, Insert, Delete, Home, End, Page Up, Page Down, the four arrow keys, Num /, and Num Enter) directly duplicate functionality that was already present on the 84-key layout in some way. To save encoding space, these keys are sent as two bytes – the first byte is always E0h, and the second byte is the (make or break) scancode of the original AT key that performed that function. As a concrete example, the regular / key sends scancode 35h, while the Num / key sends E0h, 35h. This permits the software to distinguish between these keys without using extra space in the scancode table.

This encoding also has the additional benefit that, if the underlying software only understands the 84-key layout, it will (presumably) discard the E0h byte in this example and only process the 35h byte. This would result in a / being correctly typed from the numeric keypad, even though the software doesn’t understand that this key exists.

It’s not quite that simple, however. Taking this example further, consider a user who types Shift+Num /. According to the printing on the keycap, this should still type /. But naive software looks at it this way: “Shift is down, I don’t understand what E0h means, and here comes 35h. That means they wanted to type ? here.” That’s not right, but there’s no way to fix the old software to correct it.

Here come the fake shifts.

The PS/2 keyboard contains what we would now call a microcontroller, responsible for converting the key switch signals into scancodes. It also performs self tests, drives the LEDs, and handles the typematic delay and key repeat. In the 101-key keyboard, it also gained the responsibility of deciding if and when to generate fake “Shift down” and “Shift up” messages in order to prevent the kinds of mistyping scenarios we just described.

Continuing our Num / example from before, if this key is pressed alone, the scancode sequence sent is the expected E0h, 35h. If we instead assume that the Left Shift key is already being held down, pressing Num / generates E0h, AAh, E0h, 35h – that is “fake Left Shift up” followed by “Num / down.” When Num / is released, the sequence is E0h, B5h, E0h, 2Ah – “Num / up” followed by “fake Left Shift down.” Older software interprets this as the user briefly lifting off of the Left Shift key to type a / then pressing Left Shift again, while software that understands the full 101-key layout rolls its eyes and ignores the extra shift noise.

To accurately handle all the possible keyboard states and keypress combinations is complicated, especially when one considers that the state of Num Lock also factors into this behavior when using the cursor control keys. Still, the keyboard manages to figure it out before sending anything over the wire to the system.

If that wasn’t enough of a hassle, somebody got the grand idea to reorganize a bunch of the keys between the AT and PS/2 layouts:

- Ctrl+Num Lock (Pause) was moved to the new Pause/Break key.

- Ctrl+Scroll Lock/Break (Break) was moved to Ctrl+Pause/Break.

- Shift+*/Print Screen (Print Screen) was moved to the new Print Screen/SysRq key.

- Sys Req was removed, and its function moved to Alt+Print Screen/SysRq.

Each of these changes added weirdness to the scancodes.

The PS/2’s Pause function generates scancodes for Left Ctrl and Num Lock. This sequence is prefixed by E1h rather than E0h to indicate to the keyboard controller that this is a special non-repeating key. In addition to this, many keyboards send a fake “Ctrl up” (and associated “down”) if either of the Ctrl keys happen to be down when Num Lock is pressed, to avoid unintentionally triggering the pause functionality by pressing now-unrelated keys.

The Break function Ctrl+Pause/Break generates the scancode for Scroll Lock while leaving the Ctrl key state intact. This simulates the Ctrl+Scroll Lock/Break behavior from the older layout. As with Num Lock, many keyboards send a fake “Ctrl up” while handling Scroll Lock to prevent accidental triggering of the break functionality.

The Print Screen function generates scancodes for Left Shift and Num * to simulate the Shift+*/Print Screen from the older layout.

The SysRq function Alt+Print Screen/SysRq generates the scancode 54h, which refers to the old Sys Req key.

All of the above manipulations employ logic to ensure that, regardless of the state of Ctrl, Alt, Shift, or any other keys, the user’s intent is carried out as seamlessly as possible.

The Keyboard Controller

Once the keyboard’s electrical signals enter the actual system unit, they are decoded and processed by the keyboard controller. On the IBM PC and XT, this is an Intel 8255 Programmable Peripheral Interface chip. There isn’t actually much that this chip is responsible for – its job is to listen for serial data from the keyboard, verify that it arrived intact, store each incoming scancode in a buffer, and request an interrupt so it can be read by the software. The rest of the PPI’s purpose in life is to read the status of configuration switches on the system board and manage a variety of unrelated control signals (like the speaker enable circuit).

With the advent of the AT and the need for bidirectional communication with the keyboard, the beefier Intel 8042 Universal Peripheral Interface chip was introduced. This performs all of the keyboard functions that the older PPI handled, as well as scancode translation and two-way communication. It also remains responsible for some, but not all, of the control signals that the PPI managed. In systems so equipped, it handles PS/2 mouse input as well.

From the standpoint of a programmer who is only interested in the keyboard as a read-only device, the PPI and UPI work more or less identically. When a scancode byte arrives from the keyboard, it is copied to a buffer in the keyboard controller and an interrupt is raised (IRQ 1, which appears as interrupt 9 to software). The interrupt handler can read a byte from I/O port 60h to capture the scancode for further processing. Once that is complete, the interrupt handler must explicitly acknowledge the IRQ at the interrupt controller to re-arm it for the next keyboard event. This is accomplished by writing an “end of interrupt” signal byte to I/O port 20h.

There is a slight difference between the PPI and the UPI in terms of how the keyboard input buffer is managed. The PPI will hold a byte in its input buffer indefinitely until the software acknowledges that it has completed the read. The acknowledgment procedure is to briefly strobe the high bit of I/O port 61h on, then off. When this occurs, the keyboard controller resets its buffer status and resumes reading from the keyboard. On the UPI this is much more straightforward; merely reading the value at I/O port 60h implicitly resets the buffer status. Most keyboard interrupt handlers will simply strobe the high bit of I/O port 61h for all machines, whether PC/XT or AT, even though this has no apparent effect on the AT.

Scancodes arrive one byte at a time, and one interrupt at a time, even if it is a multi-byte code. The default BIOS keyboard interrupt handler maintains several flags in the BIOS data area to simplify the state management, but custom keyboard interrupt handlers must track it themselves.

KeyboardInterruptService()

The KeyboardInterruptService() function is called in response to the keyboard interrupt event and maintains the state of the keyboard variables. The keyboard service is called whenever any key is pressed or released, regardless of what is happening elsewhere in the program.

This function is bound to interrupt vector 9, which is raised whenever the keyboard controller’s one-byte output buffer is full. This may happen due to a key being pressed (make condition) or released (break condition). Each keyboard interrupt receives a single scancode byte from the keyboard hardware – if a scancode is encoded into multiple bytes, the keyboard interrupt will be raised repeatedly to process each byte individually.

This interrupt runs through the system’s Programmable Interrupt Controller on IRQ 1, so the interrupt must be explicitly acknowledged so it can correctly retrigger later.

void interrupt KeyboardInterruptService(void)

{

lastScancode = inportb(0x0060);

outportb(0x0061, inportb(0x0061) | 0x80);

outportb(0x0061, inportb(0x0061) & ~0x80);

The interrupt keyword tells the compiler to handle this function a little differently – it must explicitly save every single CPU register on entry, restore them all before returning, and use the special “interrupt return” instruction to restore the CPU flags while returning to the interrupted code. It also needs to be very explicit when addressing the data or extra segments, because they are not guaranteed to be pointing anywhere useful.

The call to inportb() reads a data byte from I/O port 60h, which addresses the data buffer of the system’s keyboard controller. This buffer holds the most recent byte of data that the keyboard sent. This value is saved in the global lastScancode variable.

The subsequent inportb()/outportb() calls rapidly pulse bit 7 at I/O port 61h to 1, then back to 0. This strobes the “clear keyboard” flag on the 8255 Programmable Peripheral Interface chip – a piece of hardware that was only present on the IBM PC and XT. On those systems, this indicated to the keyboard controller that the scancode had been read from the output buffer, and that the next scancode byte (if one is waiting) can be shifted into its place.

The AT system, which the game was designed for, used an 8042 Universal Peripheral Interface chip as the keyboard controller and did not respond to this command. On this system, merely reading the output buffer with inportb(0x0060) is enough to indicate to the keyboard controller that the buffer has been read. The dance at port 61h appears to have no observable effect.

At this point, whether requested explicitly by writing to port 61h or implicitly by reading from port 60h, the keyboard controller’s “output buffer full” status flag has been cleared. It is ready to receive a new byte of keyboard data, whenever it comes.

if (lastScancode != SCANCODE_EXTENDED) {

if ((lastScancode & 0x80) != 0) {

isKeyDown[lastScancode & 0x7f] = false;

} else {

isKeyDown[lastScancode] = true;

}

}

This new scancode is parsed to determine if it represents a make, break, or extended code.

As the keyboard design evolved from the 83-key PC layout to the 101-key PS/2 layout, some new keys were added while others were duplicated from existing keys. The duplicated keys were assigned multi-byte scancodes: The first byte is E0h, and the second byte is the scancode of the older key it duplicates. In this way, regular Enter is 1Ch, while the Enter key on the numeric keypad is E0h, 1Ch. This allows software that wishes to differentiate the keys to do so, while older software that isn’t aware of the extension would discard the E0h prefix and handle both Enter keys in the same, presumably reasonable, way. This code is framed with such an E0h (SCANCODE_EXTENDED) check, discarding the byte whenever it appears. This permits (more or less) all of the keys on a 101-key keyboard to do something rational.

Scancodes in the range 0h–7Fh represent make codes, while scancodes in the range 80h–FFh represent break codes. The low seven bits of a break code are the same as the make code for that key, so the high bit can be thought of as the make/break flag with the low seven bits uniquely identifying one of the keys.

In the case where the high bit is 1, the identified key has been released. In that case, mask off the high bit and use the remaining bits to locate the correct element in the isKeyDown[] array, setting it to false.

Otherwise the key has been pressed and the scancode can be used as-is. Update the appropriate element in the isKeyDown[] array to true.

if (isKeyDown[SCANCODE_ALT] && isKeyDown[SCANCODE_C] && isDebugMode) {

savedInt9();

} else {

outportb(0x0020, 0x20);

}

}

This is an interesting find, and something I’m not sure anyone else has discovered: If the game’s debug mode is on (isDebugMode is true) and the keys Alt+C are pressed, the original keyboard interrupt handler function (savedInt9) is called. This is not something that typically ever happens, and must have been something that was useful during development. Perhaps this key combination, possibly augmented by holding additional keys, invoked a debugger or other terminate-and-stay-resident program. We can only guess at this point.

Otherwise, the byte 20h is written to I/O port 20h. This I/O port addresses the command register on the system’s programmable interrupt controller (PIC), and the value 20h encodes a “nonspecific end-of-interrupt” (EOI) message that is sent to the PIC.

Note: There are two PICs in the IBM AT: The master PIC is at I/O port 20h, and the (unfortunately named) slave PIC is at port A0h. Since the keyboard is wired directly to one of the interrupt request lines on the master PIC, we can pretend the slave does not exist.

The EOI message resets the “interrupt request” line that the keyboard controller is attached to (IRQ 1), arming it for another interrupt. (Actually, because this is a nonspecific EOI, it resets all of the interrupt request lines on the PIC, not just the keyboard’s. There’s probably an opportunity for a race condition in there somewhere.) This is one of the most important things this function actually does – if the EOI was not received, subsequent keyboard interrupt requests would not be forwarded to the processor and the keyboard would “freeze.”

Hieroglyphics, let me be specific.

The specific EOI message byte for IRQ 1 is 61h. Sending this would correctly reset the keyboard interrupt without possibly clobbering the other seven IRQ lines on the master PIC.

There’s safety in numbers, however. Most software that I’ve looked at acknowledges keyboard interrupts with nonspecific EOIs, and why fight the trend if it works well for others? This could very well be a case where trying to do things the correct – but uncommon – way will expose bugs and misbehavior in some people’s oddball computers and configurations.

Having updated the global keyboard state and reset the hardware for its next event, the function returns. Control passes back to whatever function was running at the time the interrupt was received, leaving it completely unaware that anything had happened.

IsAnyKeyDown()

The IsAnyKeyDown() function returns true if any key is currently pressed, without regard to which key it is. It does not block or wait for any input – the state of the keyboard at this instant is used in the determination.

bbool IsAnyKeyDown(void)

{

return !(inportb(0x0060) & 0x80);

}

Similarly to the first line of KeyboardInterruptService(), inportb() reads one byte from the keyboard controller’s output buffer (I/O address 60h). This returns the most recent byte that the keyboard sent – either 0h–7Fh for a make code, or 80h–FFh for a break code. By masking the low bits away, we are left with 0 for make codes, and 80h for break. Negating this returns true for a make code, and false for a break code.

The more appropriate name for this function would be “was the most recent scancode received a make code?” but that obscures the apparent intent of how this is used – it’s meant to return a reasonable approximation of whether any key is down. It can be tricked by pressing multiple keys simultaneously then releasing one of them, but for most common interactions it works correctly.

This does not handle interrupts, nor does it explicitly reset the keyboard controller the way that KeyboardInterruptService() does; it merely snoops the content of the keyboard controller buffer for its own purposes. Technically merely reading from this buffer on the AT keyboard controller has the side-effect of clearing the “buffer full” flag, which could interfere with the keyboard interrupt service’s ability to read the value (or vice-versa, depending on which part of the code read the buffer first) but in practice this never seems to cause issues. Still, it’s something to be aware of.

More than one way to do it.

This function could’ve based its logic on the scancode value held in the global

lastScancodevariable, avoiding a redundantinportb()call. It also would’ve been possible to uniquely determine if a key was down, while accurately considering multiple simultaneous keypresses, by iterating through each element of the globalisKeyDown[]array and returning true after the first true value was encountered.The fact that neither of these approaches was taken suggests that maybe this function’s implementation predates the creation of the keyboard interrupt handler.

The return value of the function is a boolean value in a byte-sized integer: true if any key is down and false otherwise.

WaitForAnyKey()

The WaitForAnyKey() function waits indefinitely for any key to be pressed and released, then returns the scancode of that key.

byte WaitForAnyKey(void)

{

lastScancode = SCANCODE_NULL;

while ((lastScancode & 0x80) == 0) ;

return lastScancode & ~0x80;

}

The function begins by zeroing out the lastScancode variable, setting it to a value that should never be stored by any keyboard event (SCANCODE_NULL).

A while loop is entered which continually tests the highest bit of lastScancode – as long as it is zero, the loop repeats. The zero value previously written satisfies this test, as do any keyboard make code(s) that arrive during this wait. As long as the user does nothing, or presses and holds keys, execution stays here.

While execution waits in the while loop, the keyboard interrupt handler is free to service keyboard requests and will update the value in lastScancode in response. As soon as any key is released, lastScancode receives a break code with a high bit of 1, which stops the loop from executing.

Once the loop stops, the key break code in lastScancode has its high bit zeroed, converting it into the corresponding make code, and this value is returned to the caller.