Assembly Drawing Functions

All of the procedures that draw tile image data to the screen were originally written in assembly language for speed. Assembly programming for DOS is an interesting topic, but in the context of graphics drawing it is mind-numbingly repetitive and the bigger concepts can become muddled. The approach taken here is to translate the assembly into operable C code that performs the same steps in practically the same way. The code presented here works identically to the game’s assembly, although it runs noticeably (and at times unplayably) slower. For those interested in the way the original assembly was constructed, the Cosmore project1 implements a reconstruction of the assembly code with copious comments.

The system requirements of the game specify that an “AT class” computer is required to run the game. The original IBM PC/AT uses a 6 MHz CPU clock, which appears not to be powerful enough to play the game without a noticeable reduction in frame rate.2 The later revisions of the AT use an 8 MHz clock, which runs at an acceptable frame rate but with some minor graphical glitches.3 The Intel 80386 processor had been available for six years by the time the game was released, and the 80486 for three years, therefore it was a tad unlikely that players were actually trying to play this game on a stock eight-year-old PC/AT.

As each frame of gameplay renders, the bulk of execution time is spent in one of the procedures on this page. It’s a reasonable estimate to say that there can be as many as one thousand draw calls to generate one frame, and the nominal frame rate is 10–11 frames per second. Assembly language implementations of the drawing procedures were definitely a necessity to get the game to perform acceptably on the widest range of computers.

Whodunit?

During my research into the game, other games of the era, and published code examples, I found an interview that Todd Replogle gave to Peter Bridger in 2001. It contains the following exchange:

Bridger: If John Carmack called you up today, and offered you a job at id software, would you take it?

Replogle: No. I’d [sic] be a tempting offer. Again, what is the future of video games? Oh BTW, John deserves credit for helping me code some low level code in Duke Nukem One. I’m not a very good assembly language programmer, and John was kind enough to help make Duke successful with well-written optimal assembly.

—Strife Streams, “Todd Replogle Interview (from 2001)” 4

Cosmo and the original Duke Nukem are extremely similar games from a technical standpoint, to the point that it would not be unreasonable to think that some of John Carmack’s work is present in both games. Carmack was the undisputed king of squeezing performance out of the EGA hardware, and Replogle certainly had access to Id through their shared relationship with Apogee Software.

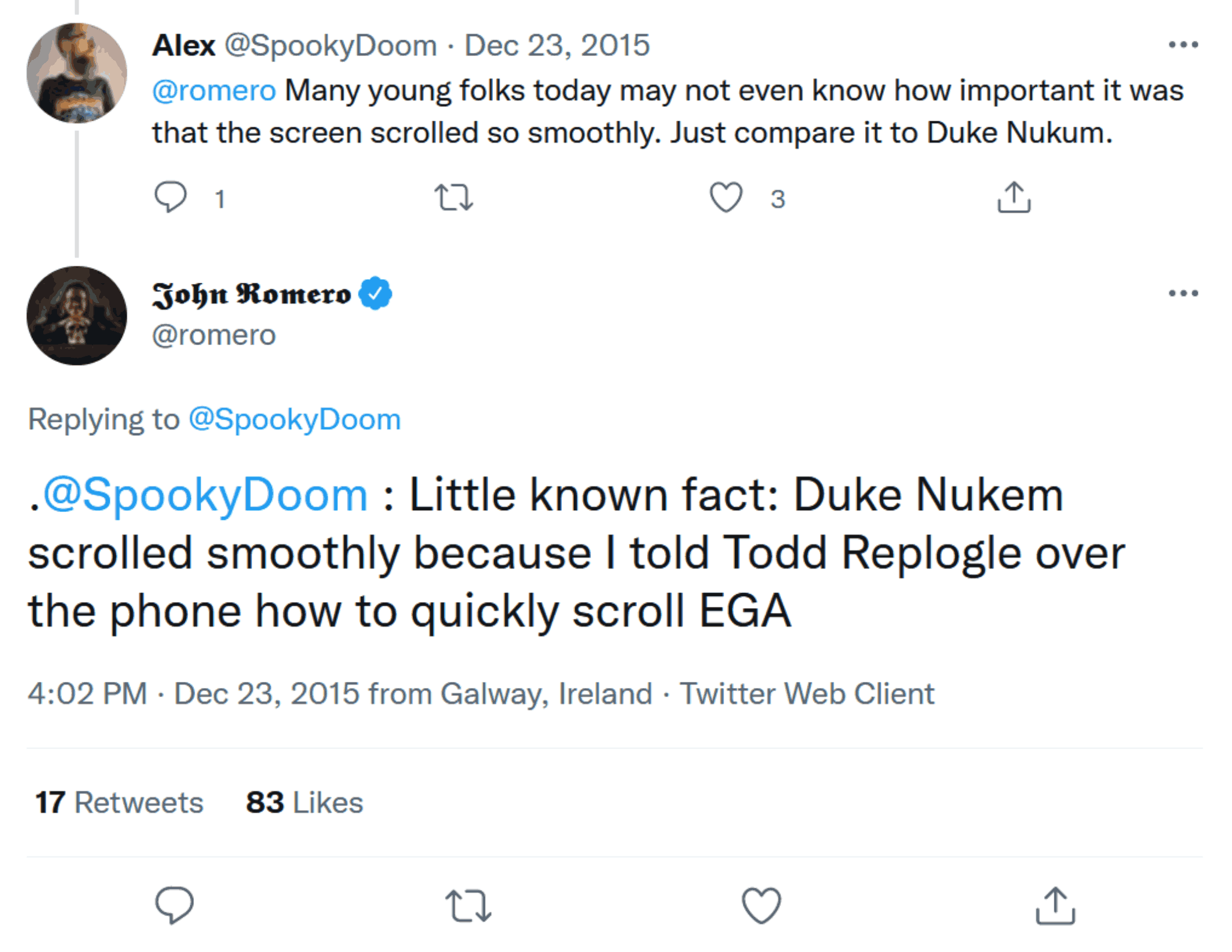

The purported connections to Id Software continue in a brief Twitter exchange between Alex Dumproff and John Romero from late 2015:

Alex (@SpookyDoom): @romero Many young folks today may not even know how important it was that the screen scrolled so smoothly. Just compare it to Duke Nukum [sic].5

John Romero (@romero): .@SpookyDoom : Little known fact: Duke Nukem scrolled smoothly because I told Todd Replogle over the phone how to quickly scroll EGA6

Dumproff is comparing the smooth scrolling techniques of Id’s Commander Keen in Invasion of the Vorticons (1990) to the comparatively chunky movement in Duke Nukem (1991). Romero’s claim is… suspicious. Duke doesn’t really have any hardware scrolling to speak of – the screen moves in eight-pixel increments and is redrawn from scratch every frame. Cosmo works the same way, with the addition of a parallax scrolling backdrop layer that moves in four-pixel increments. Neither game uses the sub-tile screen panning techniques from the Keen series, so it’s unclear exactly what Romero is recalling here.

Being Fair

I have no doubt that Romero and Replogle spoke at some point, but I have to wonder if the discussion was around a different topic, or if the discussed techniques ended up not being used in the final game.

Authorship aside, the final code is a (generally) lean workhorse.

The Data Paths of the EGA

The EGA card is complicated. It contains planar memory, palette mappings, latches, ALUs, and additional glue components that sometimes do and sometimes don’t transform data as it passes through each component. It’s somewhat easier to break the card into functional pieces and examine each individually. The three main data paths through the EGA are: video memory to screen, video memory to CPU (reading graphics back), and CPU to video memory (writing graphics).

Video Memory to Screen

In the video mode used by this game (mode Dh), each 320 × 200 screen frame contains 64,000 pixels. Each pixel can be set to one of 16 colors, requiring four bits to encode. The EGA memory is organized into four planes of 64,000 bits each. Each plane represents a single color component (red, green, blue, or intensity), each bit in a given plane maps to a single pixel on the screen, and each byte in a plane maps to a span of eight horizontal pixels.

As an example, to address the 70th pixel from the left of the screen and the 10th pixel down in this 320 × 200 mode, the calculation is as follows: Each line contains 320 horizontal pixels (aka 320 bits), which is equivalent to 40 bytes. The 10th line down therefore starts at byte offset 400. Measuring 70 pixels from the left is 70 bits or, more correctly, 8 bytes plus 6 bits. Therefore the final memory offset for this pixel is the 6th bit at byte offset 408. To set this pixel to a specific color, this offset must be written four times, once for each memory (color) plane.

Note: The EGA lacks any method to directly set a single bit in any of its memory bytes. Before writing data, the programmer must program the EGA’s registers to “mask off” the bits that should not change. When the CPU next writes a value, the EGA rewrites the byte in its memory using the content of its latches (see below) for the masked bits and the CPU data for the unmasked bits.

The four-bit value held in memory is used as an index into a palette table, which converts it into the real color value that is sent to the display. By default the palette is configured so that memory plane 3 can be thought of as the “intensity” plane, plane 2 as “red,” plane 1 as “green,” and plane 0 as “blue.” The hardware does not contain any intrinsic guarantees that color will always behave this way, but this works as long as the default palette table entries are not reconfigured.

Each byte of the EGA’s memory space, as viewed by the CPU, corresponds to one byte multiplied across these four planes.

Video Memory to CPU

It might seem odd to include the read-back capability of the EGA’s memory, but it’s an important detail to achieve certain visual operations. The memory that comprises a screen page appears as an 8,000 byte block of address space to the CPU. These 8,000 bytes are the only window available into the 32,000 bytes of data that comprise the four planes of the full screen.

The EGA supports two read modes. In Read Mode 0, the EGA is programmed via the “Read Map” register to specify which one of the four memory planes appears to the CPU. In this mode, the CPU can read the memory four times, once per plane, to reconstruct the complete color values.

In Read Mode 1, the CPU writes a color value to the four-bit “Color Compare” register, and during read operations the CPU will see a “1” in any pixel position where the color (across all four planes) matches the “Color Compare” value, and “0” if there is no match. There is also a set of “Color Don’t Care” register bits, where any combination of planes can be excluded from the comparison. It’s possible to set “Color Don’t Care” on all four planes, in which case the EGA will return solid “1” bits regardless of the screen content. This has some non-obvious uses that come into play later.

There is a critically important piece of logic in the read path: latches. Each color plane has its own 8-bit latch, which is a piece of memory that holds the last byte value read from that plane. Any time the CPU reads from video memory, regardless of the circumstances or state of the registers, all four latches are refreshed with the byte present at that position in the corresponding plane’s memory. The latches don’t have any apparent use when reading, but the values they hold are frequently used during writes.

In both reading and writing, there are some occasions where the actual data moving from or to the CPU is irrelevant; in those cases the latches are doing the real work.

CPU to Video Memory

Much like with reading, the EGA supports multiple write modes. There are three in total, but this game only uses two of them. In Write Mode 0, the CPU’s data is written directly into one (or more) memory planes. The four-bit “Map Mask” register is used to select which plane(s) will receive the written value – this allows the CPU to update as many as four video memory bytes by writing only a single byte of data.

Write Mode 1 has the rather odd property of ignoring the data provided by the CPU entirely, instead using the contents of the latches to set memory data. This can be leveraged to perform four-byte-at-a-time copy operations with only a single-byte CPU read followed by a single-byte write.

In both of these modes, a “Bit Mask” register is available to selectively disable writes to certain bit positions during each write. The bit mask applies to all four planes, conceptually serving as a pixel mask. The EGA’s memory can’t actually update certain bits while leaving others intact, so it must fetch the masked-off bits from the latches. This means that, if the program wishes to update some pixels in a byte without touching neighboring pixels, the memory position must first be read (into the latches) before being written back.

The remaining Write Mode 2 is used for bulk-filling data, which this game does not use.

DrawSolidTile()

The DrawSolidTile() procedure copies an 8 × 8 pixel solid tile from the tile storage area byte offset src_offset to the video memory byte offset dst_offset. Both offsets refer to locations within the EGA’s memory segment. The EGA hardware must be in “latched write” mode for this procedure to work correctly. The destination draw page address is influenced by drawPageSegment.

Each source tile is eight bytes long, and occurs on an eight-byte interval. The destination address refers to a planar memory offset, with each bit representing one screen pixel position. For every single-byte change to dst_offset, the screen position moves eight pixels (one tile width) horizontally. A 40-byte change to dst_offset moves one pixel vertically, and a 320-byte change moves eight pixels (one tile height) vertically.

This procedure is used to draw the solid areas of the game map and backdrops. It is also used to draw the background areas of the in-game status bar and a handful of menu UI elements.

void DrawSolidTile(word src_offset, word dst_offset)

{

word row;

byte *src = MK_FP(0xa400, src_offset);

byte *dst = MK_FP(drawPageSegment, dst_offset);

During the Startup() function when the program first began, a call to CopyTilesToEGA() loaded 64,000 bytes of tile image data into the EGA’s memory. The two display pages are at EGA segment addresses A000h and A200h, and just above the second display page (at segment address A400h) the tile storage area begins. MK_FP() combines this segment address and the caller-provided src_offset value to compute the src pointer to the first byte of tile image data to be copied.

Similarly, the current drawPageSegment value points to the segment address of whichever draw page is currently being constructed (this should be the one that is not currently being displayed). MK_FP() combines this segment address and the caller-provided dst_offset value to compute the dst pointer to the screen location where this tile should be drawn.

for (row = 0; row < 8; row++) {

*dst = *(src++);

dst += 40;

}

}

Each tile image is eight pixels high, and each of these pixel rows is eight pixels wide. Because each pixel occupies a single bit of CPU address space, an eight-pixel tile row fits into an eight-bit byte of address space. Due to these properties, combined with the quadrupling effect of the EGA’s memory planes, eight iterations of a one-byte copy operation is sufficient to draw the full tile.

The body of this loop performs a surprising amount of work thanks to the properties of the EGA’s internal logic components. src points to an arbitrary source tile byte somewhere in the EGA’s memory. When src is dereferenced and the value read, the EGA internally reads four bytes of its memory, one byte per plane, and stores the values into its four latches. Based on the EGA’s read mode setting, whatever it may be, the four bytes are collapsed into a single-byte value that is returned to the CPU. This value is completely irrelevant – the act of setting the latches is what actually matters here.

This procedure requires the calling code to have placed the EGA into “latched write” mode (aka write mode 1) and this requirement comes into play now. When dst is written, the “latched write” mode instructs the EGA to discard the byte from the CPU and instead use the contents of the four latches as the values to be written to the four memory planes. These latches were filled with four bytes of source tile image data previously, so the EGA is essentially doing a four-byte block copy between two offsets within its own memory, without the data actually passing through the CPU at all.

Note: For several of the procedures described on this page, it’s critically important to understand why and how a single-byte

*dst = *srccopies four bytes of memory, without the actual dereferenced value having any importance.

Having performed the copy for one row of image data, the src pointer is advanced by one byte and dst is advanced by 40 bytes. This sets up the next iteration of the loop to operate on the next row of image data for this tile.

DrawSpriteTile()

The DrawSpriteTile() procedure copies an 8 × 8 pixel masked tile from the byte pointer src to the video memory tile location identified by column x and row y. The destination draw page address is influenced by drawPageSegment.

src should point to the first byte of a masked tile’s image data. Valid values for x are 0–39, and 0–24 for y.

This procedure is used to draw player and actor sprites, decorations, font characters, and any other transparent tiles that are not part of the game map.

void DrawSpriteTile(byte *src, word x, word y)

{

word plane;

byte *dst = MK_FP(drawPageSegment, x + yOffsetTable[y]);

The dst pointer refers to a location in the EGA’s planar memory, with each bit representing one screen pixel position. For every single-byte change in memory offset, the screen position moves eight pixels (one tile width) horizontally. A 40-byte change moves one pixel vertically, and a 320-byte change moves eight pixels (one tile height) vertically. yOffsetTable[] is an array of the first 25 multiples of 320, which is used to quickly skip to the correct byte offset for the requested tile row y. For the column, simply adding x to the offset skips to the correct tile column.

The drawPageSegment value points to the segment address of whichever draw page is currently being constructed (this should be the one that is not currently being displayed). MK_FP() combines the segment and offset into a usable pointer.

for (plane = 0; plane < 4; plane++) {

word row;

byte *localsrc = src;

byte *localdst = dst;

byte planemask = 1 << plane;

The outer loop runs four times, once for each memory plane in the EGA. Planes are processed in blue-green-red-intensity order. The src and dst pointers must be rewound for each plane, so rather than modify them directly, copies in localsrc and localdst are created for the actual work. planemask translates the plane being operated on from an integer (0–3) to a single-plane map mask value (1, 2, 4, or 8).

outport(0x03c4, (planemask << 8) | 0x02);

outport(0x03ce, (plane << 8) | 0x04);

The first outport() sends two I/O bytes in one word-sized operation: Port 3C4h gets byte 2h, and port 3C5h gets the value in planemask. I/O port 3C4h is the EGA’s sequencer address register, which specifies the address (2h) that the sequencer’s data register should point to. I/O port 3C5h is that data register, and address index 2h refers to the “Map Mask” parameter. This receives the value planemask, which has the effect of limiting writes to just the one plane being written during this iteration.

The next outport() works similarly. Port 3CEh gets byte 4h, and port 3CFh gets the value in plane. I/O port 3CEh is the EGA’s graphics controller address register, which specifies the address (4h) that the graphics controller’s data register should point to. I/O port 3CFh is that data register, and address index 4h refers to the “Read Map Select” parameter. This receives the value plane, which selects one plane of video memory to be visible to the CPU during read operations.

The combined effect of these sets up a 1:1 correspondence between the CPU’s address space and a single plane of video memory. The three planes not being operated on have no effect on any subsequent reads or writes.

for (row = 0; row < 8; row++) {

*localdst = (*localdst & *localsrc) | *(localsrc + plane + 1);

localsrc += 5;

localdst += 40;

}

}

}

There are eight rows in a tile image, which is the level that this for loop operates on. Since we’re acting on a single memory plane, each bit represents one pixel, and one byte is a sufficient amount of data to draw a full row of pixels.

At this point, a reminder of the byte packing in masked tile image data is helpful:

| Offset | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Transparency mask (0b = opaque, 1b = transparent) |

| 1 | Blue plane |

| 2 | Green plane |

| 3 | Red plane |

| 4 | Intensity plane |

This pattern repeats every five bytes in the source data.

When each loop iteration begins, localsrc is pointing to the 0th byte in the pattern, which is the transparency mask. The first half of the expression (*localdst & *localsrc) reads the pixel values currently on the screen, and turns off any pixels where the mask specifies the tile is opaque. The second half of the expression *(localsrc + plane + 1) reads the source data byte for the current plane, skipping over the 0th mask byte.

By ORing the former by the latter, the masked tile row is overlaid on the existing screen contents. This is written back to the video memory at localdst, completing drawing for this plane’s row. To prepare for the next iteration, localsrc is advanced by five bytes and localdst is advanced by 40 bytes. This places both the read and write pointers at the correct location for handling the next pixel row.

Note: Transparent areas of the tile must have zeros for all four of the plane bits at that position, otherwise unintended pixels in

localdstmight be affected.

Once this process occurs across all four memory planes, the sprite tile has been drawn.

DrawSpriteTileFlipped()

The DrawSpriteTileFlipped() procedure copies a vertically-flipped 8 × 8 pixel masked tile from the byte pointer src to the video memory tile location identified by column x and row y. The destination draw page address is influenced by drawPageSegment. The flip is achieved by drawing the rows in reversed order, keeping the column ordering intact. This produces a vertical flip, not a rotation.

src should point to the first byte of a masked tile’s image data. Valid values for x are 0–39, and 0–24 for y.

This procedure is used to draw actors that are being destroyed, ceiling-mounted elements, or new items that are spawning into existence.

void DrawSpriteTileFlipped(byte *src, word x, word y)

{

word plane;

byte *dst = MK_FP(drawPageSegment, x + yOffsetTable[y]);

for (plane = 0; plane < 4; plane++) {

word row;

byte *localsrc = src;

byte *localdst = dst + 280;

byte planemask = 1 << plane;

outport(0x03c4, (planemask << 8) | 0x02);

outport(0x03ce, (plane << 8) | 0x04);

for (row = 0; row < 8; row++) {

*localdst = (*localdst & *localsrc) | *(localsrc + plane + 1);

localsrc += 5;

localdst -= 40;

}

}

}

This works identically to DrawSpriteTile(), so very little will be repeated. The only differences are:

localdstis initialized todst + 280during setup for each plane, which sets the draw position to the eighth pixel row (7 × 40).localdstis decremented by 40 after each row is drawn.

These two changes are all that is necessary to draw the sprite flipped vertically.

DrawMaskedTile()

The DrawMaskedTile() procedure copies an 8 × 8 pixel masked tile from the byte pointer src minus 16,000 to the video memory tile location identified by column x and row y. The destination draw page address is influenced by drawPageSegment. While broadly similar to DrawSpriteTile(), they are not interchangeable.

src should point to the first byte of a masked tile’s image data. Valid values for x are 0–39, and 0–24 for y.

This procedure is used to draw transparent areas of the map. Due to manipulations to the src pointer and the EGA’s write mode setting, this is the only thing it should be used for.

void DrawMaskedTile(byte *src, word x, word y)

{

word plane;

byte *dst = MK_FP(drawPageSegment, x + yOffsetTable[y]);

EGA_MODE_DEFAULT();

for (plane = 0; plane < 4; plane++) {

word row;

byte *localsrc = src - 16000;

byte *localdst = dst;

byte planemask = 1 << plane;

outport(0x03c4, (planemask << 8) | 0x02);

outport(0x03ce, (plane << 8) | 0x04);

for (row = 0; row < 8; row++) {

*localdst = (*localdst & *localsrc) | *(localsrc + plane + 1);

localsrc += 5;

localdst += 40;

}

}

EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE();

}

The overall structure of this is very close to DrawSpriteTile(), so only the differences between these two implementations will be detailed.

EGA_MODE_DEFAULT();

When the procedure begins, EGA_MODE_DEFAULT() resets any changes that have been made to the graphics controller’s operating parameters. The only parameters that the game reconfigures are the read/write modes, so this simply sets them back to their default values.

A brief look at the calling function is needed to explain why this is necessary. The only place this procedure is called from is DrawMapRegion(), which begins by setting EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE() before map drawing begins. Latched write mode is appropriate for the solid map tiles and backdrop areas that are drawn by DrawSolidTile(), but the latched write mode is no longer appropriate when a masked map tile is encountered. The write mode is reset – at least temporarily – so this one tile can be drawn properly.

byte *localsrc = src - 16000;

Within the outer loop, the localsrc pointer is set up to point to the position 16,000 bytes before the provided src pointer. This is again a quirk of the way DrawMapRegion() calls this procedure: It takes the value from the map data, adds it as an offset to maskedTileData’s address, and that is the value passed in src. The caller doesn’t consider that the map file format uses 16,000 as a split point to differentiate solid tiles from masked tiles, so that offset correction has to be done here.

Note: This behavior can be quite dangerous if the caller is not expecting it. If the intention is to use the 0th byte of a memory area as the tile source, the caller must use an offset of 16,000 to access it.

EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE();

Before the procedure returns, EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE() returns the EGA to latched write mode, which is the state the caller expects it to be in.

DrawSpriteTileTranslucent()

The DrawSpriteTileTranslucent() procedure copies a translucent outline of an 8 × 8 pixel masked tile from the byte pointer src to the video memory tile location identified by column x and row y. The destination draw page address is influenced by drawPageSegment.

src should point to the first byte of a masked tile’s image data. Valid values for x are 0–39, and 0–24 for y.

This procedure is used to draw the Translucent Pusher Robot sprites. The color effect is achieved by unconditionally turning on the intensity bit for every pixel that the sprite’s mask covers. The color effect here fundamentally changes the colors of pixels, meaning that “magenta” areas become “bright magenta” and no longer match for palette animation purposes.

void DrawSpriteTileTranslucent(byte *src, word x, word y)

{

word row;

byte *dst = MK_FP(drawPageSegment, x + (y * 320));

The construction of the dst pointer is identical to DrawSpriteTile(), except here the Y offset is calculated directly instead of using a lookup table. The end result is the same either way.

outportb(0x03c4, 0x02);

The outportb() call writes the byte 2h to I/O port 3C4h. This is the sequencer address register, which receives the index value 2h to point to the “Map Mask” parameter. By itself this does nothing, but any subsequent writes to port 3C5h will change the map mask data without needing to reprogram this index.

for (row = 0; row < 8; row++) {

byte setlatch;

Each tile contains eight rows, and the loop body operates on a full row of pixels during each iteration. The setlatch variable is a dummy variable which highlights operations that have the side-effect of setting the EGA’s latches.

outport(0x03ce, (~(*src) << 8) | 0x08);

outportb(0x03c5, 0x08);

On the first outport(), port 3CEh gets the byte 8h, and port 3CFh gets the inverted value that src points to. I/O port 3CEh is the graphics controller address register, which receives the index value 8h. This points to the “Bit Mask” parameter. I/O port 3CFh is the graphics controller data register, now pointing to this bit mask, and the source data is written there.

The masked tile image data pointed to by src contains color data in mask-blue-green-red-intensity order, with all the color information for one pixel row interleaved into a five-byte pattern. src points to the 0th byte of this pattern, so *src returns the mask bits for a single eight-pixel tile row. The tile image format uses “1” to indicate transparent areas, which is backwards relative to the EGA’s bit mask conventions (a mask bit of “1” indicates that that bit of memory should be changed). By taking the bitwise NOT of the source value and using it as the EGA’s bit mask, the hardware is instructed to preserve the values in any pixel position where the tile is transparent, and to rewrite the values in positions covered by the tile.

On the subsequent outportb(), port 3C5h gets the byte 8h. This is the sequencer data register, which had been configured before the for loop was entered to point to the map mask. By setting the map mask to 8h, the EGA is configured to send CPU data to the intensity plane only, leaving the other three color planes with their previous values.

setlatch = *dst;

*dst = 0xff;

Now the EGA hardware does the heavy lifting for us. dst points to the address for this output tile row within the EGA’s memory. The value at that position is read into a throwaway variable (setlatch) by the CPU, while the significant copy of this data is retained in the EGA’s latches. When the read is complete, the latches contain a copy of the contents of the eight pixels at this screen position.

The value FFh is written back to the same location in dst, which is subject to several modifications within the EGA. Firstly, only the intensity plane is selected for writing, limiting the possible effects of this write to just this one plane. Additionally, the bit mask has been loaded with the transparency information for the tile, meaning that some bits (those that are not covered by an opaque area of the sprite) will refuse the value from the CPU and instead retain the original value held in the latches.

The combined effect of this is, the intensity plane’s bits are turned on in positions where the tile is opaque. Uncovered pixels in the transparency mask, and all pixels on the red/green/blue planes, remain unmodified. This has the effect of brightening any pixels covered by the tile.

Goes Both Ways

Instead of writing FFh to the EGA’s memory here, 0h could just as easily be sent. This would turn off the intensity bits that are covered by the tile, making the image appear darker in those areas. As this is a fairly bright game to begin with, the darkening effect is arguably much more impactful.

src += 5;

dst += 40;

}

}

Finally, the pointers are advanced to prepare for another iteration of the loop. src is advanced by five bytes, and dst is advanced by 40 bytes, placing both pointers in the correct position to process the next row of tile image data.

DrawSpriteTileWhite()

The DrawSpriteTileWhite() procedure copies a solid white outline of an 8 × 8 pixel masked tile from the byte pointer src to the video memory tile location identified by column x and row y. The destination draw page address is influenced by drawPageSegment.

src should point to the first byte of a masked tile’s image data. Valid values for x are 0–39, and 0–24 for y.

This procedure is used to draw sprites which are “activated,” taking damage, or flashing to grab the player’s attention.

void DrawSpriteTileWhite(byte *src, word x, word y)

{

word row;

byte *dst = MK_FP(drawPageSegment, x + yOffsetTable[y]);

Like most of the drawing procedures (e.g. DrawSpriteTile()), this uses MK_FP() to construct the dst pointer to the video memory byte to be written.

outportb(0x03c5, 0x0f);

outport(0x03ce, (0x10 << 8) | 0x03);

outport(0x03ce, (0x08 << 8) | 0x05);

Multiple I/O writes occur to configure the EGA to draw the outline of the tile.

The first outportb() writes the byte Fh to I/O port 3C5h. This is the sequencer data register, which has not been explicitly set here to point to a specific parameter. Something should have set the index value at port 3C4h prior to this to specify which parameter should receive this byte.

The assumption is that I/O port 3C4h has previously been set to 2h, pointing this data register to the “Map Mask” parameter. This is done explicitly at the end of SetVideoMode(), and the map mask is the only thing on the sequencer that ever gets programmed in this game, so this is relying on the fact that nothing messed with the sequencer address since then. Setting the map mask to Fh has the effect of writing all four memory planes with any data bytes written by the CPU, which is what generates the bright white color.

During the second outport(), port 3CEh gets the byte 3h, and port 3CFh gets the byte 10h. I/O port 3CEh is the graphics controller address register, which receives the index value 3h. This points to the “Data Rotate/Function Select” parameter. I/O port 3CFh is the graphics controller data register, now pointing to this parameter, and the value 10h is written there.

The data rotate/function select parameter has the following interpretation:

| Bit Position | Value (= 10h) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 7–5 (most significant) | 000b | Not used. |

| 4–3 | 10b | Function Select: Written CPU data is OR’d with the latched data. |

| 2–0 (least significant) | 000b | Rotate Count: Unrotated. |

With the function select parameter set this way, a “1” bit written by the CPU will turn a pixel value on, but a “0” bit will retain the contents in the latches.

Finally, the third outport() sends the byte value 5h to I/O port 3CEh, and the byte value 8h to port 3CFh. The port meanings are the same as the previous write, only the index (5h) and data (8h) values change. This programs the value 8h into the EGA’s “Mode Register” parameter. The mode has the following interpretation:

| Bit Position | Value (= 8h) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 7–6 (most significant) | 00b | Not used |

| 5 | 0b | Shift Register: The meaning here is not well-documented, but this is the default state for this parameter. |

| 4 | 0b | Odd/Even: Disables this CGA compatibility addressing mode. |

| 3 | 1b | Read Mode: The CPU reads the results of the comparison of the four memory planes and the color compare register. |

| 2 | 0b | Diagnostic Test Mode: Disabled. |

| 1–0 (least significant) | 00b | Write Mode: Each memory plane is written with the CPU data rotated by the number of counts in the rotate register, unless Set/Reset is enabled for the plane. Planes for which Set/Reset is enabled are written with 8 bits of the value contained in the Set/Reset register for that plane. |

The only non-default setting here is the read mode: When the CPU reads data from the EGA memory in this mode, the color value across all four planes is compared against the “Color Compare” register and the result of this test is returned to the CPU. However, in the original setup of the display hardware in SetVideoMode(), all four memory planes were added to the “Color Don’t Care” mask, meaning that we don’t actually care about the value currently held in any of the planes and any color value should be treated as a match. The combination of these two settings means that all subsequent reads from video memory will return FFh to the CPU regardless of what’s actually held there.

for (row = 0; row < 8; row++) {

*dst &= ~(*src);

src += 5;

dst += 40;

}

Each tile contains eight rows, and the loop body operates on a full row of pixels during each iteration.

The &= operator begins by reading one byte from the video memory pointed to by dst. Due to the configuration of the EGA’s read mode and “Color Don’t Care” registers, the returned value is always FFh. As a side effect of this read, the EGA’s internal latches are set with the actual pixel values held in all four memory planes.

src points to the 0th byte of data for a row of masked tile image data. This data is built from a repeating five byte pattern consisting of mask-blue-green-red-intensity for each row. The zeroth byte is the mask for this row, with “1” bits indicating transparent areas. This mask is inverted with a bitwise NOT, and the result is combined with the read dst value (FFh) using a bitwise AND. FFh bitwise-AND any value is that value, which means the tile row’s inverted mask is written back to dst.

During the write, the EGA’s “function select” comes into play. Recall that, before the for loop was entered, the EGA was programmed to OR the incoming data with the latched data during a write operation. In positions where the CPU writes a “1” bit (areas where the tile is opaque), the CPU’s data will prevail and a “1” will be written to that position in memory. In positions where the CPU writes a “0” bit (transparent areas), the resulting value will be either “1” or “0” depending on what is present in that position in the latches.

Because the map mask was set to Fh, the write is performed across all four memory planes, involving all four latches, in parallel. Writing a “1” bit across all four planes creates bright white – the color we wish to see. Writing a “0” bit causes the latched value – either “1” or “0” – from each plane to persist in that position

Finally, the pointers are advanced to prepare for another iteration of the loop. src is advanced by five bytes, and dst is advanced by 40 bytes, placing both pointers in the correct position to process the next row of tile image data.

outport(0x03ce, (0x00 << 8) | 0x03);

EGA_MODE_DEFAULT();

}

Once all eight tile rows have been drawn, outport() and EGA_MODE_DEFAULT() revert the changes made when the procedure was entered. The graphics controller’s “Data Rotate/Function Select” parameter (3h) gets zero. This resets the “function select” value from earlier:

| Bit Position | Value (= 0h) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 4–3 | 00b | Function Select: Data written from the CPU to memory is not modified. |

EGA_MODE_DEFAULT() resets the “read mode” value that was previously changed.

LightenScreenTile()

The LightenScreenTile() procedure lightens the entire area at the video memory tile location identified by column x and row y. The destination draw page address is influenced by drawPageSegment. Valid values for x are 0–39, and 0–24 for y.

This procedure is used to brighten areas of the screen that are completely illuminated beneath Light Beam (west edge), Light Beam (center), and Light Beam (east edge) actors. The effect is achieved by turning on the intensity bit on every pixel in the screen tile. The color effect here fundamentally changes the colors of pixels, meaning that “magenta” areas become “bright magenta” and no longer match for palette animation purposes.

void LightenScreenTile(word x, word y)

{

word row;

byte *dst = MK_FP(drawPageSegment, x + yOffsetTable[y]);

Like most of the drawing procedures (e.g. DrawSpriteTile()), this uses MK_FP() to construct the dst pointer to the video memory byte to be written.

EGA_BIT_MASK_DEFAULT();

outportb(0x03c5, 0x08);

The call to EGA_BIT_MASK_DEFAULT() allows all eight pixel positions in each byte to be modified during memory writes from the CPU.

The subsequent outportb() writes the byte 8h to I/O port 3C5h. This is the sequencer data register, which has not been explicitly set here to point to a specific parameter. Something should have set the index value at port 3C4h prior to this to specify which parameter should receive this byte.

The assumption is that I/O port 3C4h has previously been set to 2h, pointing this data register to the “Map Mask” parameter. This is done explicitly at the end of SetVideoMode(), and the map mask is the only thing on the sequencer that ever gets programmed in this game, so this is relying on the fact that nothing messed with the sequencer address since then. Setting the map mask to 8h has the effect of writing just the intensity plane with any data bytes written by the CPU, leaving the red/green/blue planes alone. This prepares the hardware to produce the brightening effect.

for (row = 0; row < 8; row++) {

*dst = 0xff;

dst += 40;

}

}

Each tile contains eight rows, and the loop body operates on a full row of pixels during each iteration.

dst points to the byte of video memory that represents the current row of tile pixels. The value FFh is written here and, due to the effect of both the EGA’s map mask and the bit mask, all eight bits of the intensity plane are turned on. The remaining planes are unaffected, resulting in a brightening at any pixel position that did not already have its intensity bit turned on.

The dst pointer is advanced by 40 bytes, preparing the write position to operate on the next row of tile pixels, and the loop continues.

Once the loop has operated on all eight pixel rows, the procedure returns without any further cleanup. Of particular importance, the map mask has not been restored here, so subsequent drawing calls must reprogram the mask if changes to anything beyond the intensity plane are desired.

LightenScreenTileWest()

The LightenScreenTileWest() procedure lightens the lower-right half of an 8 × 8 tile at the video memory tile location identified by column x and row y. The destination draw page address is influenced by drawPageSegment. Valid values for x are 0–39, and 0–24 for y.

This procedure is used to brighten the topmost tile of Light Beam (west edge) actors. The brightening effect works similarly to that in LightenScreenTile(). The color effect here fundamentally changes the colors of pixels, meaning that “magenta” areas become “bright magenta” and no longer match for palette animation purposes.

void LightenScreenTileWest(word x, word y)

{

word row;

byte *dst = MK_FP(drawPageSegment, x + yOffsetTable[y]);

byte mask = 0x01;

Like most of the drawing procedures (e.g. DrawSpriteTile()), this uses MK_FP() to construct the dst pointer to the video memory byte to be written.

mask holds the eight-bit pixel pattern to use to illuminate each row of the tile. During the first iteration of the loop, only the single rightmost pixel is lit, represented by only the least significant bit being set.

outportb(0x03c5, 0x08);

This outportb() writes the byte 8h to I/O port 3C5h. This is the sequencer data register, which has not been explicitly set here to point to a specific parameter. Something should have set the index value at port 3C4h prior to this to specify which parameter should receive this byte.

The assumption is that I/O port 3C4h has previously been set to 2h, pointing this data register to the “Map Mask” parameter. This is done explicitly at the end of SetVideoMode(), and the map mask is the only thing on the sequencer that ever gets programmed in this game, so this is relying on the fact that nothing messed with the sequencer address since then. Setting the map mask to 8h has the effect of writing just the intensity plane with any data bytes written by the CPU, leaving the red/green/blue planes alone. This prepares the hardware to produce a brightening effect.

for (row = 0; row < 8; row++) {

byte setlatch;

outport(0x03ce, (mask << 8) | 0x08);

Each tile contains eight rows, and the loop body operates on a full row of pixels during each iteration. The setlatch variable is a dummy variable which highlights operations that have the side-effect of setting the EGA’s latches.

outport() writes the byte value 8h to I/O port 3CEh, and mask to port 3CFh. I/O port 3CEh is the graphics controller address register, which receives the index value 8h. This points to the “Bit Mask” parameter. I/O port 3CFh is the graphics controller data register, now pointing to this bit mask, and the value held in mask is written there. This sets up the shape of the light cone on this row of pixels.

setlatch = *dst;

*dst = mask;

Here again, we rely on the internal hardware of the EGA to do the work for us. dst is pointing to a byte of video memory that holds the pixels that have already been drawn to the screen at this tile row. By reading this memory location, the value in the video memory is persisted into the EGA’s latches, and a pointless value is returned to the processor. This is placed into the setlatch variable, where it is never touched again. The setting of the latches is all that matters here.

Next, the value of mask is written back to the video memory at the same dst location. Several elements of the EGA’s state come into play here. Firstly, the map mask is configured to only allow this write to affect the intensity plane. Secondly, the bit mask restricts the bit positions that can be changed, leaving the remaining positions to keep the values from the latches. Finally, the actual value written has an effect on what the qualifying pixel positions are set to.

Because the bit mask and the value being written are the same, we can think of them as a unit. Anywhere mask has a “1” bit, the corresponding bit in the intensity plane is turned on. Anywhere mask has a “0” bit, the value from the latch remains and the pixel’s color does not change.

As the value in mask changes, the pattern of lightened pixels changes to match.

dst += 40;

mask = (mask << 1) | 0x01;

}

}

The dst pointer is advanced by 40 bytes, preparing the write position to operate on the next row of tile pixels.

The value in mask is shifted one bit position to the left, and the least significant bit is forced on. This shifts binary ones in from the right, and zeros out from the left, generating the next step in the triangular pattern that defines this edge of the light cone.

With everything set up to process another row of tile pixels, the loop continues until all eight rows have been drawn.

LightenScreenTileEast()

The LightenScreenTileEast() procedure lightens the lower-left half of an 8 × 8 tile at the video memory tile location identified by column x and row y. The destination draw page address is influenced by drawPageSegment. Valid values for x are 0–39, and 0–24 for y.

This procedure is used to brighten the topmost tile of Light Beam (east edge) actors. The brightening effect works similarly to that in LightenScreenTile(). The color effect here fundamentally changes the colors of pixels, meaning that “magenta” areas become “bright magenta” and no longer match for palette animation purposes.

void LightenScreenTileEast(word x, word y)

{

word row;

byte *dst = MK_FP(drawPageSegment, x + yOffsetTable[y]);

byte mask = 0x80;

outportb(0x03c4, 0x02);

for (row = 0; row < 8; row++) {

byte setlatch;

outport(0x03ce, (mask << 8) | 0x08);

setlatch = *dst;

*dst = mask;

dst += 40;

mask = (mask >> 1) | 0x80;

}

}

This works identically to LightenScreenTileWest() except for two differences:

Firstly, the outer outportb() is unsafe in rather the opposite way: It sets the sequencer address register (3C4h) to point to the “Map Mask” parameter (2h), but doesn’t actually write map mask data at any point. This procedure relies on the fact that something has previously set this mask to 8h (limiting write operations to just the intensity plane) without making this explicit.

This works correctly due to luck, mostly. This procedure is only called from DrawLights(), which makes numerous calls to LightenScreenTile() and LightenScreenTileWest(), which both set the map mask to the value expected by this procedure. Due to the way maps are authored, it’s almost a guarantee that, if a map has lights on it, a piece of west or center light will have been drawn before an east piece is encountered.

The second difference is in the handling of mask. Here it starts at 80h, setting only the most significant bit (leftmost pixel) to start with. During each row, the value in mask is shifted one bit position to the right, and the most significant bit is forced on. This shifts binary ones in from the left, and zeros out from the right, generating the next step in the triangular pattern that defines this edge of the light cone.

Aside from these details, the implementation is the same as LightenScreenTileWest().

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY()

The DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY() macro wraps a call to DrawSolidTile(), converting x and y tile coordinates into the linear offset form expected by that function.

#define DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(src, x, y) { \

DrawSolidTile((src), (x) + ((y) * 320)); \

}

Each pixel row on the screen uses 40 bytes, and each tile row is eight pixels high. Multiplying these two values produces the Y-stride value of 320.

https://github.com/smitelli/cosmore/blob/main/src/lowlevel.asm ↩︎

Interpolated from values given by several sources; this was tested on DOSBox with

cycles=840. ↩︎This was tested on DOSBox with

cycles=1120. ↩︎https://web.archive.org/web/20220518080826/https://www.strifestreams.com/ToddReplogleInterview2001 ↩︎