EGA Functions

Neither the original IBM Personal Computer nor the PC/XT came with any sort of onboard video hardware. If the owner of one of these systems wanted to see anything (and they most certainly would’ve wanted to), they could choose between IBM’s Monochrome Display Adapter (MDA) or their Color Graphics Adapter (CGA) expansion cards. Each adapter required a different display: either the black-and-green IBM 5151 Monochrome Display for MDA, or the IBM 5153 Color Display for CGA.

When the Personal Computer/AT came around in 1984, it still lacked any onboard video capabilities. The MDA and CGA cards were still available, as was IBM’s brand-new Enhanced Graphics Adapter (EGA). The EGA card supported all of the functionality of the older MDA and CGA cards, and could drive displays that were originally designed for those cards if that’s what the user had. For the full EGA experience, the IBM 5154 Enhanced Color Display was necessary.

IBM eventually built video hardware directly into the Personal System/2 in 1987: This was the Video Graphics Array (VGA). The VGA hardware supported all the functionality of the EGA, which also meant it supported the basic functionality of the MDA and CGA as well. Unfortunately, the added color capabilities of the VGA meant that its interface had to break compatibility with the displays used on the older cards, using a completely new connector and signal format that required an IBM 851x Personal System/2 Color Display. The VGA became the most popular video card for PC clone manufacturers to copy, resulting in VGA (and its various extensions) becoming the de facto standard for PC-compatible video signals for nearly 15 years.

The EGA was an interesting middle ground for game developers in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It supported a high-enough display resolution and a rich-enough range of colors to get the visuals they required, without the disk space and computational overhead of the more expansive VGA colors. In those days, it could reasonably be assumed that anybody who was seriously interested in playing games would have an EGA card in their system at the very least, if not a higher-end VGA that fully supported the EGA programming techniques.

The EGA programming techniques, as it turns out, are unabashedly arcane. The card’s design has so many dark corners and underdocumented behaviors, programmers like Michael Abrash and John Carmack were able to ascend to their almost godlike status in part by figuring out how to bend the EGA’s hardware to do their bidding. This game uses the EGA, although without nearly as much trickery as Carmack had to do in the games he worked on. Still, one really needs to understand how the hardware is put together at a fairly low level to get production-grade results.

This page aims to explain not just the programming aspects of the EGA, but also the overall design of its hardware – these display technologies and signaling schemes are thoroughly obsolete by modern standards, but they are interesting nonetheless.

People Don’t Like Electrons Shooting At Their Face

Computer displays and television sets up until the early 2000s were built around a cathode ray tube (CRT). Compared to the flat screens we are all used to looking at today, CRT-based displays are big, bulky, relatively fragile, power-hungry, and generate a lot of waste heat. We put up with that because that was really the only viable display option available at the time. CRTs had been used in television sets since the 1930s, and in primitive oscilloscopes before that.

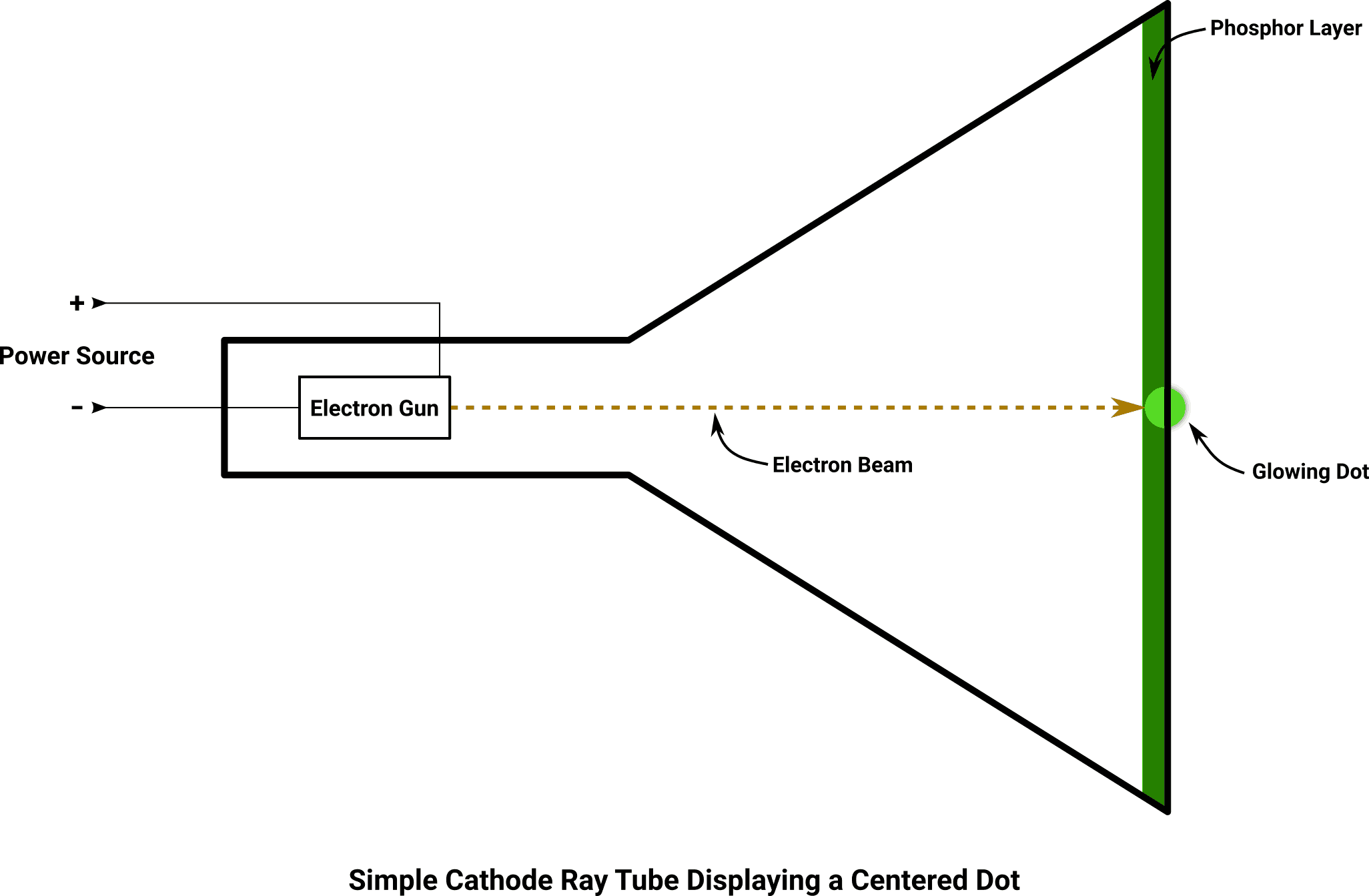

The picture on a CRT is generated principally by a device called an electron gun, which converts electrical power into a narrow beam of electrons moving with substantial kinetic energy. When used in displays, the electron gun is near the back of the unit, aiming its energy directly at the viewer. Most people don’t like electrons shooting at their face, so the electron gun is enclosed in a glass tube (the CRT itself) with a thick glass screen to stop the electrons before they reach the viewer. To reduce the amount of energy wasted by electrons colliding with air molecules, all the pressure is sucked out of the tube during manufacture and a vacuum is sealed inside it.

The human eye can’t see electrons as emitted from the electron gun, so the inside of the screen is coated in something we can see: phosphor. Normally phosphor looks like a plain crystal or powder, but when it gets hit with a beam of electrons, it converts the kinetic energy into visible light. By turning electricity into high-velocity electrons, then using that energy to light up bits of phosphor, the building blocks of image generation are realized.

Putting all this together, we get… a dot. A single, tiny, bright dot at the center of the screen. The electron gun only emits in one direction, and the beam is about as narrow the period at the end of this sentence. Clearly we need something else if we want to light up the whole surface of the screen.

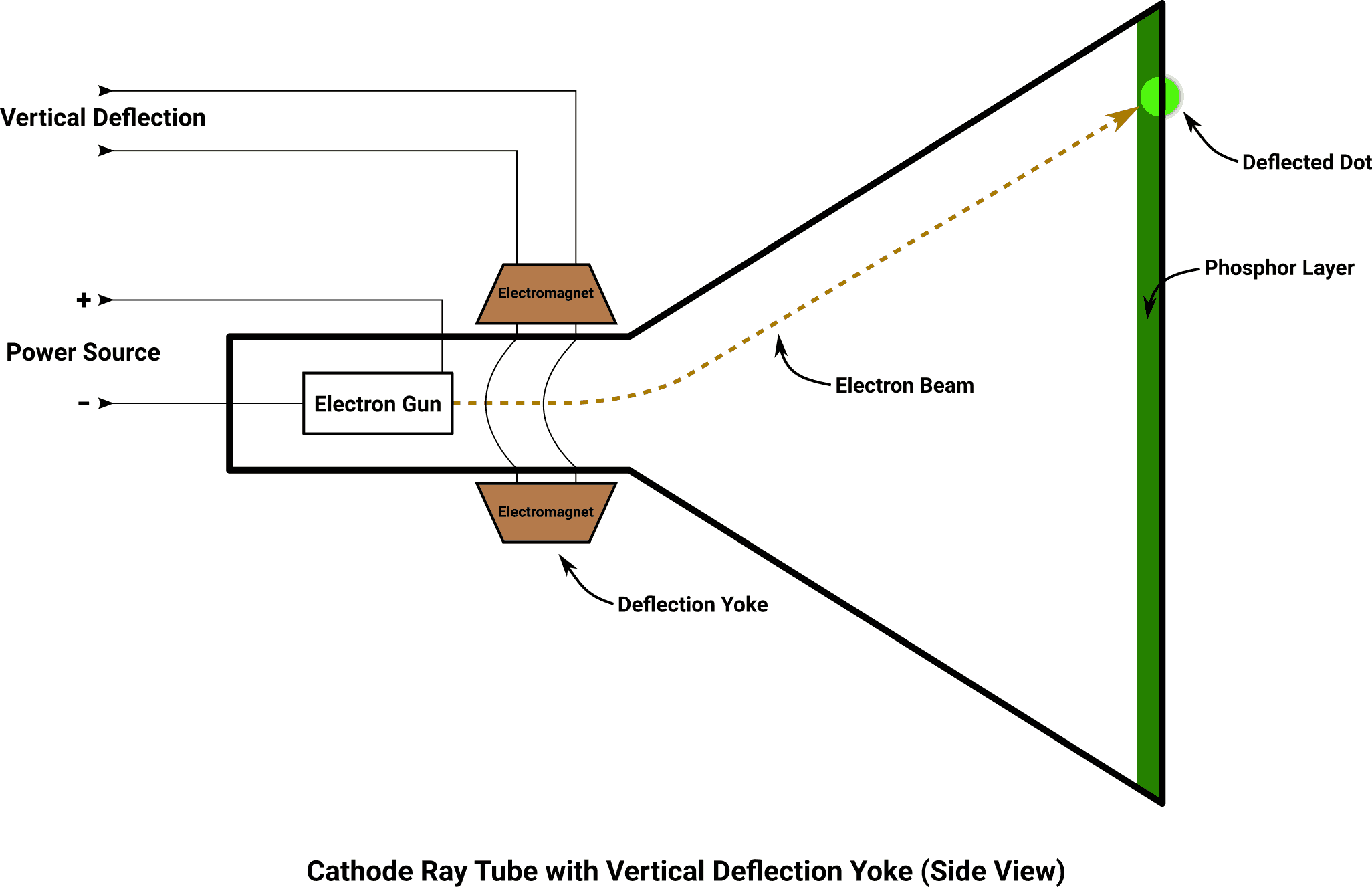

It turns out that the electron beam is highly susceptible to magnetic fields, and one can use a carefully-placed magnet to attract or repel the beam (deflect it) pretty much anywhere along the face of the screen. In fact, anything that emits a magnetic field can deflect the beam, including an electrical current through a coil of wire. By carefully winding wire to create an electromagnet, then mounting that magnet to the CRT between the electron gun and the screen, we can move the dot up and down by varying the current through the electromagnet’s coils.

Adding another, separate electromagnet rotated 90° from vertical around the neck of the tube, we can independently move the dot left and right as well. The apparatus that holds these electromagnets is called a deflection yoke.

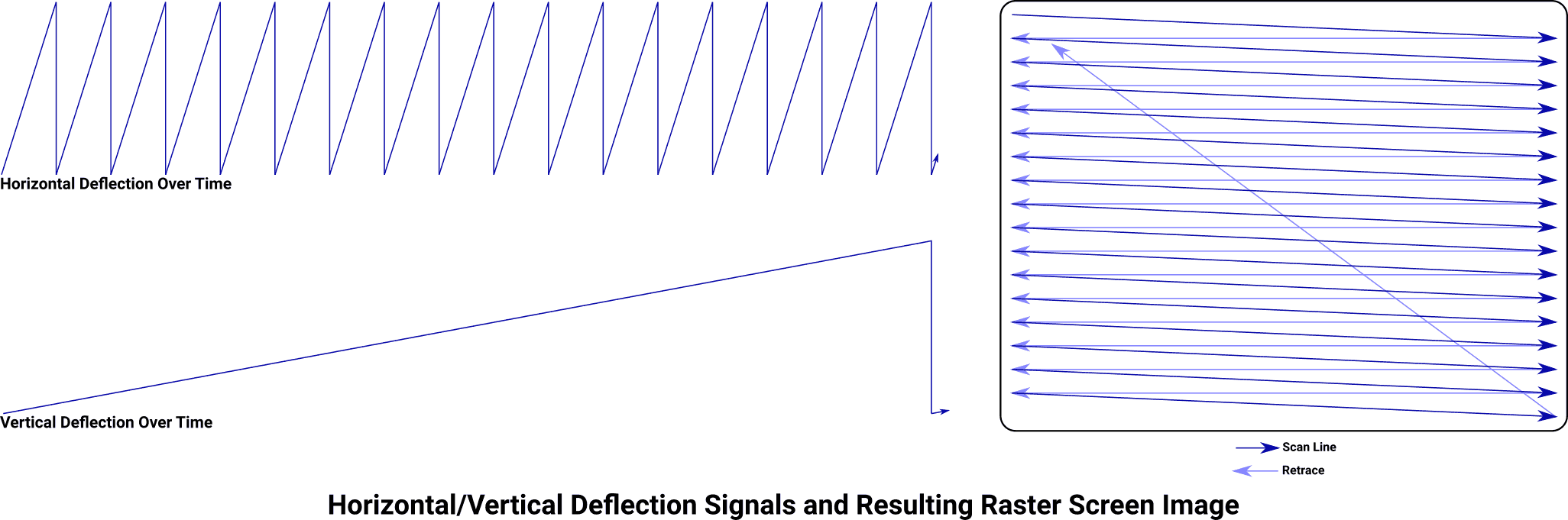

Managing the dot by hand is a lot of work and not that much fun, so let’s automate that. By constructing an oscillator that generates a triangle wave – consisting of a linear rise in voltage followed by a linear fall, repeating – and connecting that to the horizontal deflection magnet, we can make the dot “ping-pong” back and forth across the width of the screen. By changing the triangle wave into a sawtooth wave – a linear rise in voltage followed by an immediate fall – we can make the dot move from left to right over a span of time, then immediately “fly back” to the left almost instantaneously and repeat that motion.

Now let’s feed a sawtooth wave to the vertical deflection magnet instead, but do it about 400 times more slowly. The beam starts high on the screen, works its way down to the bottom, then snaps back up to the top.

Running both oscillators together, making sure they’re running at the precise frequencies and they don’t drift out of phase, a useful behavior emerges. The dot starts at the upper left corner, moves horizontally to the right edge of the screen, then snaps back to the left edge about 1 dot-height below where it previously was. After it travels horizontally across the screen 400 times, the dot ends up reaching the bottom-right corner before it snaps back to the top-left edge to repeat the process again. (Each “snap back” is referred to as a retrace.) The dot continues in this left-to-right, top-to-bottom raster pattern in the same way words are read from the pages of a book.

So, now we can light up every part of the screen, but it’s still just a moving dot. Let’s crank up the speed and see what happens. By taking the horizontal oscillator up to 24,000 Hz and the vertical oscillator to 60 Hz, the same raster scanning behavior is preserved but now the screen is being fully traversed 60 times every second. The dot is now moving so fast that we no longer perceive its motion at all. (In fact, if the screen is, say, one foot wide, the dot would be moving at a horizontal speed of over 16,000 miles per hour.)

Now the layer of phosphor covering the screen comes back into play. Pretty much as soon as a chunk of phosphor gets hit by the electron beam, it begins to glow. The glow only persists for about a millisecond before it decays back to darkness, but persistence of human vision makes it appear as though the screen is uniformly lit. Rather than displaying a fast-moving dot, our example screen is showing a bunch of horizontal lines packed so densely that they blend into a bright, solid, stable rectangle. The hard part of getting an image onto a CRT display is done.

Flickers In Time

Humans might not be able to see the scanning behavior of a CRT display, but cameras sure can. If you’ve ever pointed a camera at the picture of a CRT screen, you’ve undoubtedly seen flickering, rolling, strobing, and all kinds of unpleasant visual artifacts. The faster the camera’s shutter speed is set, the more severe the artifacts become.

From here, all that’s left to do is flash the output of the electron gun on and off so that we have some control over which pieces of phosphor get hit and which don’t. If we wanted to draw, for example, an 8x8 checkerboard pattern on the screen, we’d have to turn the electron gun on and off four times during each horizontal sweep (called a scan line), and invert the pattern after every 50th scan line. By writing much more complicated patterns at a much higher frequency, individual points on the screen can be controlled. To create variations in brightness (instead of just a simple on/off switch) we can also vary the amount of energy released by the electron gun over time, producing varying amounts of glow from the phosphor on certain areas of the screen.

The only thing tricky about all this is making sure that the circuit controlling the electron gun stays strictly in sync with both the horizontal and vertical deflection circuits that move the electron beam around, otherwise the picture will not be stable.

A Splash of Color

The previous description was accurate for a monochrome display, which has one color of phosphor (sometimes green, or amber, or really any color) that can glow at any brightness between black and its natural color. To produce an image with arbitrary colors, some extra hardware is required.

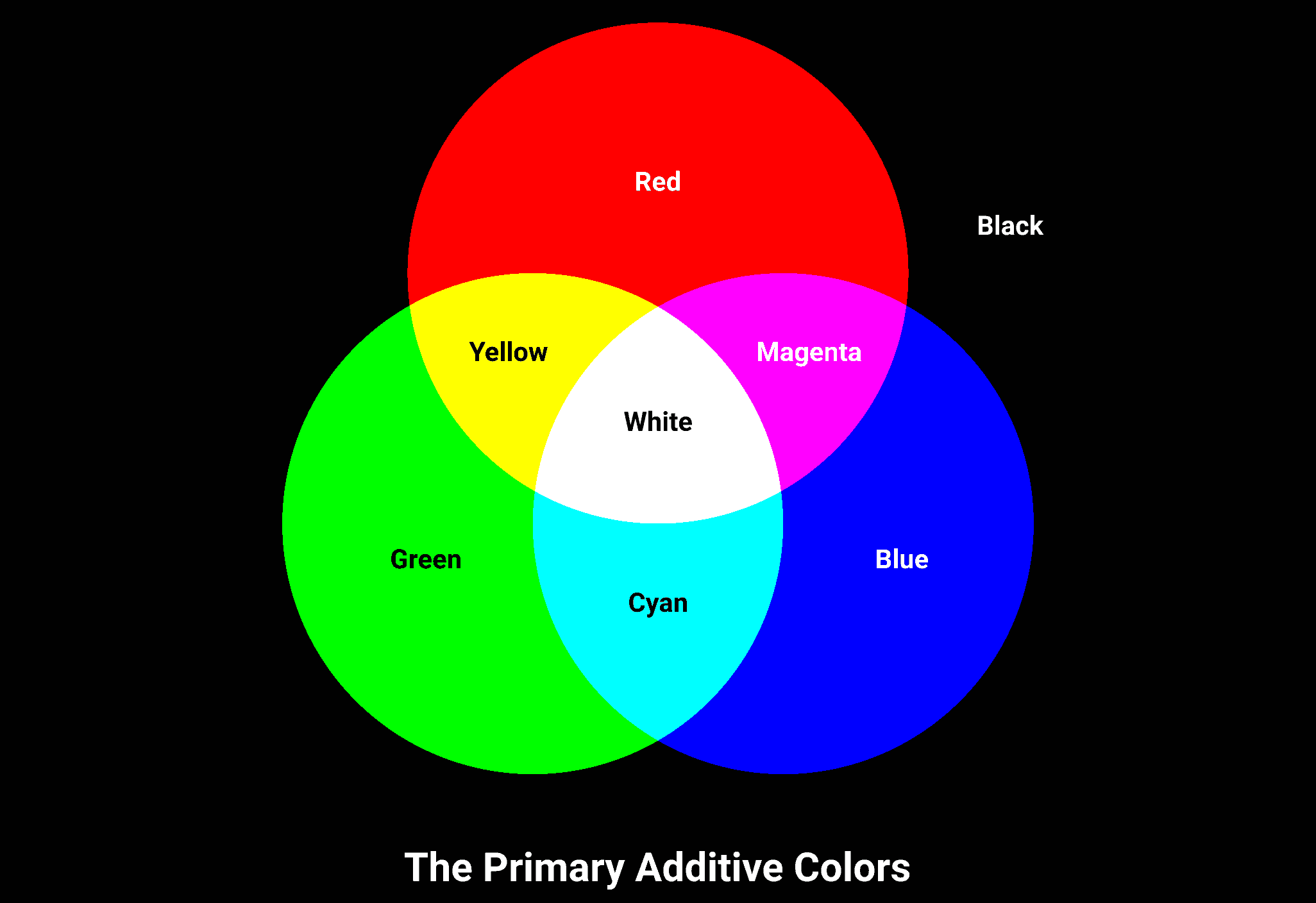

The screen of a color display is coated with three different types of phosphor, arranged in a very fine and precise pattern. When each of these phosphors is hit by an electron beam, they glow either red, green, or blue. By lighting multiple phosphors in close proximity, other colors can be created (red + green = yellow, green + blue = cyan, blue + red = magenta, red + green + blue = white). By finely mixing the ratios of these three primary additive colors, it is possible to reproduce every color in the spectrum visible to the human eye.

Note: This is contrary to what your art teacher may have taught you in school. When dealing with ink or paint on a surface, those are subtractive colors which behave differently than additive colors do.

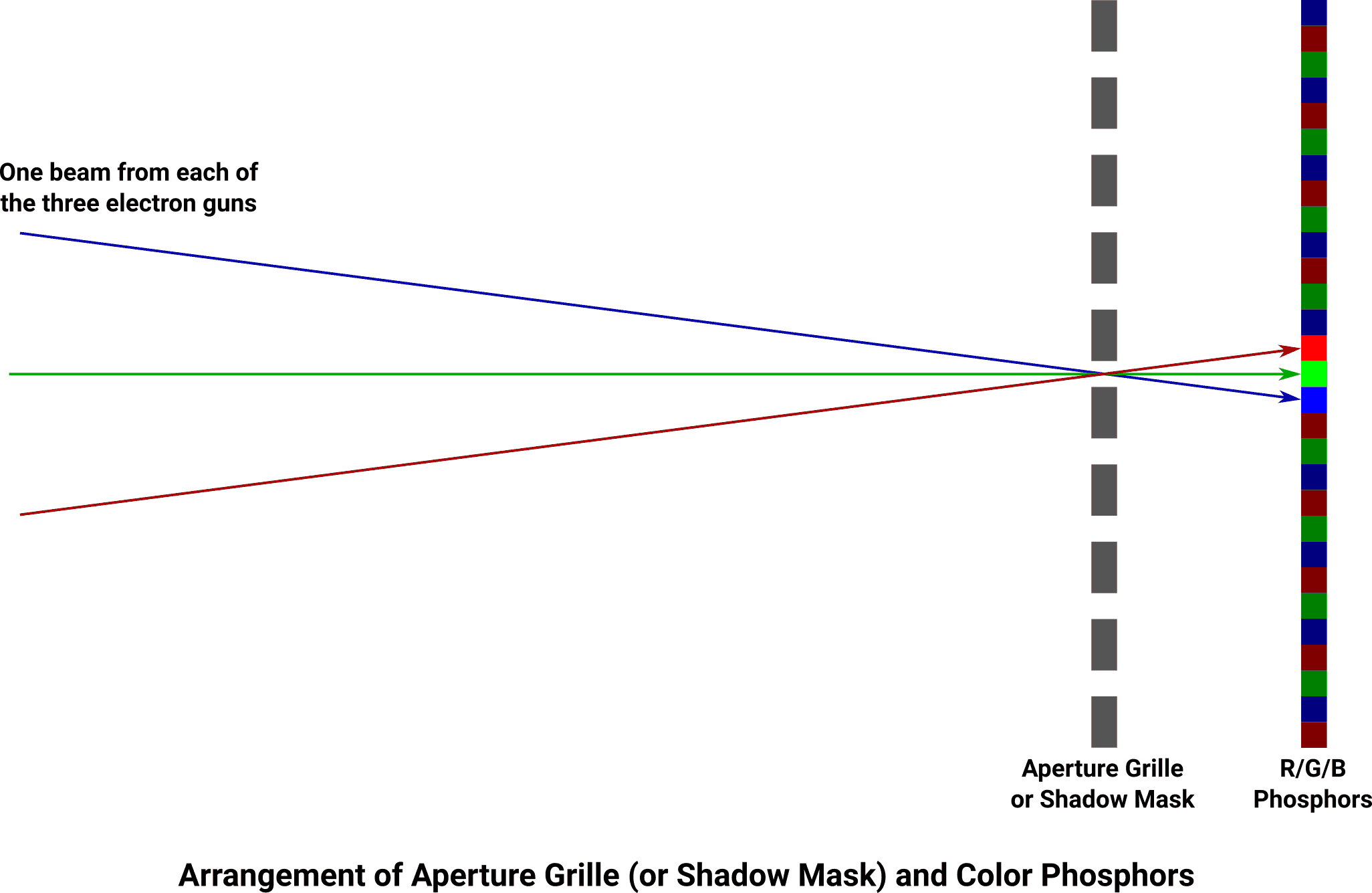

In order to facilitate this mixing, there are three separate electron guns in a color CRT display, each responsible for one of the red/green/blue components of the image. All three beams are deflected and focused as a unit by a single deflection yoke, in the same manner as on a monochrome display. In a properly-functioning CRT, running all three electron beams simultaneously will create a white dot that can be placed anywhere on the screen.

To ensure that each color of phosphor only responds to the correct electron gun for that color channel, a precision-cut metal structure is placed between the electron guns and the phosphor layer on the screen. This is either an aperture grille or a shadow mask, depending on who manufactured the tube. These devices are designed to only allow the red phosphors to be reachable from the vantage point of the red electron gun, and the green phosphors from the green gun, and likewise for blue. This ensures that each electron gun can only light up the phosphor of the appropriate color.

Dad’s gonna be mad when he sees what we did.

If you’ve ever placed a magnet near a color CRT TV or computer display, you’ve probably noticed that it is possible to “bend” the picture and generate interesting rainbow patterns in the process. This is caused by the magnet deflecting the electron beams in uncontrolled ways, permitting energy from the R/G/B guns to reach positions and phosphor colors that it shouldn’t ordinarily be able to.

If you’re overzealous in doing this, it’s possible to magnetize the metal in the aperture grille or other structural components of the display, making the distortion persistent. This can almost always be resolved by invoking the display’s built-in degauss functionality, or by turning the unit off and on so it can degauss itself automatically.

Aside from having three independent electron guns to control, everything else on a color display works the same as it does on a monochrome one.

Taking Control

Everything described up to this point happens inside the display itself. Since the entire point of the display is to be able to present images from a computer, there must be a way for the computer’s display adapter card to tell the display what to do. Such signals pass from the adapter to the display through a cable that uses a 9-pin D-subminiature connector for MDA, CGA, and EGA, or a 15-pin connector for VGA. Each of these display adapter types uses two pins on the connector for synchronization, and between two and six pins for control of the electron guns.

The MDA signal is the simplest. Its horizontal synchronization pin carries an 18.4 kHz signal, and its vertical sync pin carries 50 Hz. The adapter card generates these signals to indicate when it wants to begin a fresh horizontal scan line, and when a new vertical screenful of information (called a screen frame) is desired. The display listens for these signals, synchronizes its own internal oscillators to it, and deflects the electron beam in sync with the adapter’s request.

The MDA’s video information is carried on two pins, which can each be either on or off, for a total of four expressible intensity combinations. With both pins off, black is generated. The remaining three combinations create varying intensities of the single color the display can produce (typically green, although some displays use amber or white phosphor).

The CGA works practically identically, but it uses 15.7 kHz and 60 Hz for its horizontal and vertical frequencies, respectively. Due to the increased amount of color information, four video pins are required. As with the MDA, each of these pins can either be on or off, producing a total of 16 expressible colors. The pins carry red, green, blue, (each of which does what you would expect it to) and intensity – the intensity signal brightens all of the R/G/B color outputs by about 33% compared to what they would have produced alone.

Note: The CGA monitor contains a bit of a color hack: If the RGBI signals are ever set to 1100 (i.e. red/green are on and blue/intensity are off) the display will artificially cut the green output in half. This avoids generation of a putrid yellow, replacing it with a more generally useful brown. The computer and CGA adapter are unaware of this modification; it occurs entirely inside the display.

The EGA begins to complicate things by supporting two different synchronization modes: the 15.7k/60 Hz frequencies from the CGA, and a new EGA-specific horizontal rate of 21.85 kHz (while still using 60 Hz for vertical sync). This higher frequency permits more scan lines to be drawn each frame, which the EGA adapter can use to fit more content inside the bounds of the screen. In order to differentiate between these modes, the adapter reverses the polarity of the vertical sync signal when running in the higher horizontal frequency mode to help the display lock onto the frequency.

The EGA has six video pins: red, green, blue, red intensity, green intensity, and blue intensity. (The intensity pins here work similarly to the single intensity pin available on the CGA, except the EGA can control the intensity for each color channel independently.) As each of these six pins can be either on or off, a total of 64 colors are expressible on an EGA display.

The VGA further complicates things by only “officially” supporting 31.5 kHz as the horizontal sync frequency, but allowing either 60 Hz or 70 Hz for the vertical frequencies (again using the polarity of the vertical sync signal to help it determine the correct operating mode). The red/green/blue pins in the VGA connector are purely analog, and can support a continuously variable range of colors depending on the voltage level applied to each pin. This was also the time when third-party multisync displays started coming onto the market, which could adapt to pretty much any reasonable horizontal or vertical sync frequency and produce a stable picture. The open-ended nature of this signaling scheme allowed VGA displays to eventually support line counts and color depths far beyond those originally envisioned, and this was a major factor in why this connector survived through Super VGA resolutions and into the 21st century.

The lineage and relationships between these display standards helps make some sense of the backward-compatible baggage carried by the later cards. The EGA can do everything the MDA and CGA can do, and the VGA can do everything the EGA can do. Each adapter (and its display) needs to be able to run at the rates of its predecessors, or (in the case of EGA emulating MDA, for example) run at a new rate that can mimic the display characteristics and behavior of the older hardware. The EGA (and VGA) are complicated to program for, but that’s partially because they each contain an entire MDA/CGA clone hidden within.

Going Digital

Up until now, we’ve made the conscious choice to only refer to display capabilities in terms of synchronization frequencies and, where strictly necessary, scan line counts. The computer needs to think of things a little more concretely. Namely, it needs to know how many different vertical positions it can address (this is roughly the number of scan lines in a frame) and the number of horizontal positions it can address. The latter is an interesting property, since that’s determined principally by how fast we can flash the electron guns on and off during the course of one scan line and still be able to clearly see the results. This behavior is limited by the precision and quality of the electrical components used to build the display hardware, and we’re working on a budget here, so we’ll limit it so it’s roughly as clear in the horizontal direction as it is vertically.

By dividing the screen into rows (one per scan line) and columns (one per distinct addressable position along a scan line), we have declared a resolution for this display. Each point on the screen has an X coordinate that addresses its column, and a Y coordinate that addresses its row, uniquely identifying that location. Each of these points is called a picture element, pel, or pixel. Conventionally the top-left pixel is referred to as (0, 0) and these numbers increase as the position moves down or to the right.

Note: This places the screen in quadrant Ⅳ of the Cartesian plane, but with a negated Y axis. This can make all kinds of graphical calculations come out with a vertically-flipped result.

We now have everything needed to start devising a scheme where we can represent the state of a picture on the screen in terms of digital memory. We have a fixed-size grid of pixel positions, and each pixel has a color value selected from a fixed range. So let’s invent a display for ourselves. Earlier we used an example display that produced 400 scan lines. It’s the 1980s, so all of our TV and computer screens are using a 4:3 aspect ratio and we don’t want to buck that trend (aspect ratio is the relationship between the width and height of the screen – 4:3 means the screen is four arbitrary units wide by three units high). Since our screen has 400 lines, the number of columns should be somewhere in the neighborhood of ([4 ⁄ 3] × 400) 533.3. That’s a weird number, so we’ll round it up to 600. This display has a resolution of 600 × 400 pixels, for a grand total of 240,000 pixels on the screen.

If this screen only needs to show pure black-and-white images with no color or grayscale information, each pixel could be represented by a single binary digit (bit), packed into a series of eight-bit bytes, and fit in 30,000 bytes of memory. If, as a different example, we require the ability to choose between 16 colors at each pixel, we would need four bits, or half of a byte, to represent each pixel – bringing the total amount of memory required to 120,000 bytes. If we go hog-wild and apply modern standards, we’ll need ten bits per R/G/B channel or 30 bits per pixel, and at least 900,000 bytes of memory to represent the screen. This is almost the maximum amount of memory that the PC’s 8088 CPU could address! Just for one screen! Clearly there have to be some compromises in display resolution and/or color depth to keep the hardware requirements realistic.

Aside from the question of memory size, there is also memory speed and bus width (collectively called bandwidth) to consider. Recall that our imaginary 600 × 400 display had a horizontal sync frequency of 24,000 Hz. This means that the display is drawing one full scan line of content – consisting of 600 individual pixels – 24,000 times each second. The actual pixel clock rate, which is the product of both of those values, is 14.4 MHz. The memory underpinning this display needs to be able to deliver one pixel’s worth of data 14.4 million times per second. For 1 bit-per-pixel color depth, this is manageable at about 1.7 MiB/second. The bandwidth for 30-bit color jumps up to almost 52 MiB/second, which is unconscionable by 1980s standards. The realities of hardware design and manufacturing cost have tremendous effect on the actual designs that can reasonably be built.

Standing Tall

Continuing the exploration of our imaginary 600 × 400 display, there’s a physical discrepancy. The aspect ratio suggested by the resolution, assuming each pixel is perfectly square, would be 3:2, but the screen has a true aspect ratio of 4:3. This difference came about because our calculation for an “ideal” screen resolution was 533.3 × 400, but we rounded the width to 600 to avoid making the math weird. Our punishment for simplifying our calculation is that our pixels now aren’t actually square, they’re slightly taller than they are wide. This means that if we wrote a program to display a 100 × 100 pixel square on the screen, it wouldn’t actually show as a square – its height would display at about 113% the size of its width. There’s really nothing we can do about that other than draw everything a little bit shorter than we intend for it to display on this screen.

This is called the pixel aspect ratio (PAR), which is distinct from (but related to) the screen’s aspect ratio. PAR wasn’t just a phenomenon on computers at the time; standard-definition television had to contend with PAR when early digital tape formats were being standardized.

The VGA’s 640 × 480 resolution was the first mode that tried to guarantee perfect square display of pixels. Likewise, the 720p and 1080p/1080i television broadcast resolutions use square pixels with a 16:9 screen aspect ratio, as do the newer Ultra High Definition resolutions.

Overscan and Border

The magnetic field that controls the deflection of a CRT’s electron beam(s) has a certain amount of – for lack of a better word – inertia behind it. It can’t instantaneously stop moving and change directions; it needs to slow down, reverse, and speed back up after it reaches one of the edges of the screen. If a video signal were permitted to be displayed as the beam was performing one of these direction changes, the picture at those edges would appear squished and non-linear, and those areas would be somewhat brighter due to the beam spending relatively more of its time near those areas of phosphor.

This change in velocity is so non-linear and cumbersome to compensate for, the display simply moves the problem out of the way by deflecting the electron beam off all four visible edges of the screen and into the area behind the plastic bezel as it scans. By doing this, the unobscured areas of the screen are serviced by a beam that is moving at a constant speed, while the dirty work of decelerating and changing directions happens out of view. This concept, where the electron beam intentionally scans areas of the screen that are not visible to the viewer, is called overscan. Almost all CRT applications do this (including CRT televisions) and intentionally push meaningful parts of picture data off the screen to ensure the still-visible portions display accurately.

The display adapter in the PC stops drawing video data well before the electron beam gets anywhere near the outer edge of the visible area, since it would be quite annoying to have the first or last row/column of text blocked by the screen bezel. While the beam is outside the addressable image area, the adapter sends a constant “blank” color signal. “Blank” conventionally means “black,” but it doesn’t necessarily have to. The adapter can be configured to send any of its available colors out to the display during these intervals. This appears as a colored border surrounding all four edges of the screen’s content, usually (but not always, depending on the calibration of the display) extending out to the bezel.

This is not a feature that’s commonly used, which is why so many PC and DOS emulators can get away with not simulating it.

Text Mode

The original MDA card shipped with 4 KiB of memory and could show 80 columns and 25 rows of text on the screen. That’s 4,096 bytes to draw 2,000 characters, or two bytes (16 bits) for each character on the screen. Even with 1-bit color, 16 bits is nowhere near enough space to draw a uniquely legible symbol in any font, so clearly the programmer is not drawing anything at a per-pixel level.

I’m… I’m an action figure!

There actually was a third-party clone of the MDA called the Hercules Graphics Card that supported monochrome graphics (as well as text) on a standard IBM monochrome display.

In text mode, the video memory contains one byte for each character that appears on the screen, plus one attribute byte that contains information about how the character in that space should be drawn (inverted video, emphasized, blinking, and so on). The 80 × 25 text grid consists of 2,000 character bytes plus 2,000 attribute bytes, for a grand total of 4,000 bytes which fits comfortably into 4 KiB of memory. The actual information on how to draw each character as a dot pattern is stored elsewhere, on a ROM chip built into the adapter.

The MDA character ROM contains 256 symbols (one for each possible character byte value), each rendered on a monochrome 9 × 14 grid, for a total of just under 4 KiB of font data. As the display sweeps through a scan line, a character value is read from the appropriate position in video memory and this value is used as an offset into the character ROM. The adapter figures out which row of the character it’s currently drawing based on the number of scan lines drawn so far, and it reads a horizontal span of nine pixel bits from the character ROM out to the display, adjusting them as required by the corresponding attribute byte. This character generation scheme saves a tremendous amount of memory and processing power, since the program only has to say “put an S here” instead of “draw 126 pixels that have been pre-arranged to look like an S.”

An 80 × 25 grid of 9 × 14 font characters works out to a display resolution of 720 × 350. Even though there is no way to directly control these pixels in text mode, the display doesn’t actually care and behaves as if it were running in any other 720 × 350 resolution mode.

Palettes

Across all of the display adapter types described here, none of them are capable of using the display’s color reproduction capability to the fullest. The CGA display is capable of showing 16 colors, but there are no graphics modes available that can display more than four colors at any one time. The EGA has similar limitations, only able to display 16 of its 64 colors at once. Even the VGA is limited to 256 simultaneous colors, even though the adapter hardware can produce over 262,000 different color combinations and the display has virtually no color limitations at all.

These limitations boil down to size and speed of the video memory. There simply weren’t big-enough, fast-enough, cheap-enough RAM chips available at the time to allow the program to have unrestricted access to the entire gamut of the display’s color. These colors are available, the programmer just has to make a choice about which of the colors they want to be able to use at a given time and which will remain inaccessible.

These adapters accomplish this selection through a system called a palette in the display adapter. The palette is simply a mapping between the value written in the video memory and the value that is actually sent to the display. In the case of the CGA, the palette maps each 2-bit video memory value to a 4-bit color, EGA maps 4-bit memory values to 6-bit colors, and VGA maps a 8-bit memory values to 18-bit colors. There is a series of default palettes (one per video mode) that can be used if precise control of color is not required, giving access to the a broad range of generally useful colors which are given well-known (and often thoughtfully organized) memory values.

The organization of the mode Dh’s default palette is especially useful:

| Palette Index | Red Intensity | Green Intensity | Blue Intensity | Red | Green | Blue | Color Value | Color Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Black |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Blue |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | Green |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | Cyan |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 | Red |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | Magenta |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | Brown |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | Dark White (Light Gray) |

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 | Bright Black (Dark Gray) |

| 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 | Bright Blue |

| 10 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 18 | Bright Green |

| 11 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 19 | Bright Cyan |

| 12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 20 | Bright Red |

| 13 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 21 | Bright Magenta |

| 14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 22 | Bright Yellow |

| 15 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 23 | Bright White |

At first glance, it might seem like all of the “bright” color variants should have a greenish tinge due to the lack of either the red intensity or blue intensity bits being set. When an EGA display is running at its 15.7 kHz horizontal frequency (like it does in mode Dh), it enables a “CGA compatibility” function where it disregards any input on the red intensity or blue intensity pins and only uses green intensity as its global intensity value, limiting the available display colors to 16. Palettes are explained a bit more visually on the full-screen image format page.

Note: Compare the EGA connector pinout to the CGA for more context about why green intensity was chosen for this purpose.

In this default palette, the 0th bit in the palette index is sent to the blue output pin, the 1st bit is sent to the green pin, the 2nd bit is sent to the red pin, and the 3rd bit is sent to the green intensity pin. The red intensity and blue intensity pins are held at zero at all times. The jump from color value 7 to 16 is caused by the green intensity bit turning on instead of the blue intensity bit.

This palette arrangement is useful because the programmer can think of the memory values as if they represented “I/R/G/B” bits, since they behave that way, and forget that the palette exists at all. There is, however, no innate connection between the bit positions and the signals on the output pins; this is merely a convention that is provided by the palette. The programmer is free to rearrange the values here or even map multiple palette indexes to the same output color. The main limitation in CGA compatibility mode is that only the green intensity bit in a color value has any meaning, and it applies to all three color channels.

Planar Memory

With the CGA and its all points addressable graphics mode, the system’s processor has full control over every pixel on a 320 × 200 screen with 2-bit color depth. The memory requirements for such a screen are 128,000 bits (or 16,000 bytes). Since the video memory on the PC is memory-mapped, this results in 16 KiB of memory space that the CPU cannot use as regular system memory, since the separate video memory is occupying those addresses. This is not a terribly huge amount of space to reserve, so the CPU’s memory address space and the pixels on the screen share a 1:1 correspondence.

On a high-end decked-out EGA card, it is possible to display a 4-bit mode at 640 × 350 resolution. This requires 896,000 bits (or 112,000 bytes) of memory, which presents a small problem. First off, 112,000 bytes of address space is a lot to ask from the system – that’s over 10% of the maximum total amount of memory the 8088 can address. Secondly, this is larger than the 64 KiB segment size that has forever constrained DOS programmers, which means the CPU can’t even draw the entire picture without performing a rather slow segment register change in the middle of redrawing the screen. Additionally, the entire contents of this memory must be read by the adapter’s digital-analog converter during each frame of display, requiring over 50 megabits/second of bandwidth. The memory in IBM’s original card could barely achieve half that.

The EGA graphics modes mitigate these issues by breaking the memory up into four planes and addressing them all in parallel. This means that the video memory’s address space is reduced by a factor of four, and each byte written by the processor is actually written to four distinct byte positions in video memory simultaneously. This drops the memory address requirements for our 4-bit 640 × 350 mode down to 28,000 bytes, which is a bit more palatable.

If you’re reading this and asking how one write multiplied across four memory locations could possibly maintain addressability of every pixel on the screen… you’re absolutely right; it’s not possible to directly write 112,000 distinct bytes of video memory through a 28,000 byte window. The EGA works around this by having a set of map masks that can be configured via the EGA card’s I/O ports. By configuring the masks first, the program can select which memory planes it does and does not want a subsequent write operation to affect. In the worst case, this means that the program must write to the entire 28,000 byte address range four times, reprogramming the masks to restrict the operation to a single plane during each run. But in more ideal cases, the program can cleverly leverage the masks to write spans of solid color or other simple patterns in one-fourth as many transfers as it would’ve taken in a linearly-addressed system.

There are also controls available for the program to specify which memory planes to consider during a read operation back to the CPU, with some interesting color comparison functions available that can be leveraged as a primitive form of hardware acceleration.

The Hierarchy of the EGA

The EGA card isn’t a single unit; rather, it is a number of discrete microprocessors that work in concert to provide the functionality of a display adapter. The card contains a CRT controller (which generates the synchronization signals for the display), a sequencer (which manages access to the video memory), two discrete graphics controllers (which translate data between the formats used by the CPU and video memory), and an attribute controller (which converts memory values into R/G/B/I signals for the display). The EGA has multiple I/O port addresses that are generally directed to one of these sub-components.

| I/O Port Address(es) | Addressed Component |

|---|---|

| 3B2h, 3BAh, 3C2h, 3D2h, 3DAh | Miscellaneous |

| 3B4h, 3B5h, 3D4h, 3D5h | CRT Controller |

| 3C0h | Attribute Controller |

| 3C4h, 3C5h | Sequencer |

| 3CCh, 3CAh, 3CEh, 3CFh | Graphics Controllers |

Typically (but not always) a component will use one of its I/O addresses as an address register and another as a data register. The address register is programmed by the CPU with an index value, indicating which parameter is being referred to. The data register receives the actual data that is programmed into that parameter. By using this scheme, it’s possible to expose dozens if not hundreds of parameters while only utilizing two I/O addresses.

The Nuts and Bolts of EGA Mode Dh

This game uses EGA mode Dh, which is a 320 × 200 pixel 16-color paletted mode. The video memory resides at segment A000h and covers a full 64 KiB of address space. Using the default palette (which the game generally does not change except in rare circumstances) the values in video memory are in IRGB order (i.e. blue is the least significant bit).

Since the EGA graphics modes are planar, each read or write operation affects four bytes in memory simultaneously. The EGA planes are arranged such that all of the intensity bits are on plane 3, the red bits are on plane 2, the green bits are on plane 1, and the blue bits are on plane 0. This organization is purely a function of the palette, and only remains valid so long as the palette is not reprogrammed with values that break the scheme. These are sometimes referred to as color planes, which while not technically incorrect, does ignore the influence of the EGA’s default palette and might lead to incorrect assumptions about the behavior of some operations.

Within one plane, each consecutive bit maps to one pixel on the screen, and each consecutive byte maps to a span of eight screen pixels horizontally. Each 320-pixel display line uses a span of 40 bytes in each plane. The full screen takes 8,000 bytes of address space, or 32,000 bytes of physical video memory.

The standard EGA card contains at least 64 KiB of memory, enough to hold two different screenfuls (pages) of data. This card is upgradable to 256 KiB, which is enough space to store up to eight pages of data, or a combination of screen pages and other graphical elements. The EGA can be commanded to quickly flip its output between these pages (page flipping or ping-pong buffering) to allow it to display an image from a completely-drawn area of memory while another area is being redrawn in the background. By always flipping to a page that is not being drawn to, the program will never risk displaying a half-updated image to the user. Typically the request to change the active page is handled by the video BIOS, while the code that redraws non-visible pages typically operates directly on memory addresses for speed.

Note:

This game assumes (and does not check!) that the system has 256 KiB of EGA memory. Not all EGA cards do, and the game will not work on such cards.

The later VGA hardware, fully backwards-compatible with EGA, always has a minimum of 256 KiB of video memory and shouldn’t have any difficulties like this.

Use the BIOS, Luke

DOS game programmers almost exclusively draw screen images by writing to the video memory directly, but operations like changing video modes, display pages, and palette registers are usually done by using safe (and somewhat slow) BIOS function calls. There were enough different third-party manufacturers of display adapters in those days that, if a person decided to do everything the low-level way and bypass BIOS, there would almost always be some oddball not-quite-compatible card that wouldn’t behave the way other cards did.

Part of programming these types of games is to make judgment calls about when it’s appropriate to use BIOS (or DOS, or device drivers for that matter) to perform a task at the expense of some speed, and when to poke and prod the hardware directly. Generally this game defers to BIOS for video management, and only directly communicates with the card to send image data or configure the masks.

It’s Gonna Be C

The graphics management and low-level drawing procedures of the game were all written in assembly language for speed. While that’s interesting and everything, the bulk of the assembly code is repetitive unrolled loops and memoization of values in registers that obscure the important bits of what’s going on. If you’re genuinely interested in how the assembly looks, Cosmore1 has it.

For clarity, and the ability to assign meaningful names to things, I have translated all of the assembly code into C for commentary. The C code performs the same function as the original assembly, but it runs noticeably slower due to how poorly the compilers of the era optimize code. This game definitely needed assembly to run well on the computers it targeted.

SetVideoMode()

The SetVideoMode() procedure changes the system’s video mode to the mode number specified by mode_num, using a BIOS interrupt call. Between the MDA, CGA, EGA, and VGA, about 20 different video modes are defined by IBM specifications. Each video mode has a unique combination of display resolution, synchronization timings, color depths, text vs. graphical mode, and so forth. About half of the defined modes are valid for the EGA, which is the adapter this game is designed for.

void SetVideoMode(word mode_num)

{

_AX = mode_num;

_AH = 0x00;

geninterrupt(0x10);

The caller provides the chosen mode number in mode_num. The only value used in this game is mode Dh, which is a 320 × 200 graphics mode with 16 colors. This value is copied into the processor’s AX register. AX is a 16-bit combination of AL (the low byte of the value) and AH (the high byte). AH is then explicitly set to zero, leaving only the low eight bits of mode_num in AL.

With the registers configured, interrupt 10h is generated to execute a BIOS call for video services. This service is divided into subfunctions based on the value held in AH. Subfunction AH=0h is the “Set Video Mode” function, which takes its argument in AL. After the interrupt returns, the new mode is active.

outport(0x03ce, (0x00 << 8) | 0x07);

outport() sends two I/O bytes in one word-sized operation. I/O port 3CEh is the EGA’s graphics controller address register, which specifies the address (7h) that the graphics controller’s data register should point to. I/O port 3CFh is that data register, where address index 7h refers to the “Color Don’t Care” parameter. This receives the value zero.

Color Don’t Care controls how the four memory planes are combined into a single value during instances where the CPU is reading values back from the video memory. One of the EGA’s read modes permits the values in all four planes to be compared against a separate color reference register, with the CPU receiving a “1” bit for each pixel position where the color matches there and “0” otherwise. Color Don’t Care excludes certain planes from the comparison, treating each excluded plane as an unconditional match for the reference color. Only the low four bits of this value are defined, one bit per memory plane in 3-2-1-0 order.

This is a case where IBM’s documentation2 is either confusing or flat-out wrong. The observed behavior of this register is that a “1” bit activates comparison against the reference color, and “0” deactivates it (any color is considered to be a match, hence we “don’t care”). This is reversed from what the documentation suggests.

By zeroing out all four bits here, the program is requesting the adapter to entirely ignore the reference color in all relevant read operations, returning “1” in every bit position. (The only place this has an effect is in the DrawSpriteTileWhite() procedure.)

outportb(0x03c4, 0x02);

}

outport() sends the byte 2h to the I/O port at address 3C4h. This sets up the sequencer address register in preparation for a future write to the “Map Mask” parameter. This does not do anything by itself; this would be expected to be accompanied with a write to the sequencer data register at I/O port 3C5h to actually change the Map Mask parameter value.

Pick a paradigm and stick with it.

As far as I can tell, the thinking was as follows: The only time the sequencer is touched, it’s to reprogram the map mask. With that in mind, it makes sense to set the address register once up front and never change it again. With a constant address here, only the data register needs to be changed inside the expensive graphics code.

It didn’t always go that way. Some of the graphics procedures run with the assumption that the sequencer address register is configured correctly, and some of the graphics procedures reset it to the map mask explicitly.

This procedure returns, having placed the EGA hardware into an appropriate state.

SetBorderColorRegister()

The SetBorderColorRegister() procedure configures the display adapter to use color_value to fill the overscan area at the edges of the screen, using a BIOS interrupt call. The color value specified here is not paletted, so any of the 64 EGA colors are available for use if desired – assuming the display (and the current display mode) supports all 64 colors. The interpretation of the color value is the same as SetPaletteRegister().

void SetBorderColorRegister(word color_value)

{

_AH = 0x10;

_AL = 0x01;

_BX = color_value;

_BH = _BL;

geninterrupt(0x10);

}

All of the register assignments here are in preparation for a BIOS video service interrupt call. AH=10h is the “Set/Get Palette Registers” subfunction, AL=1h specifies that the overscan color register should be modified, and BH contains the color to program into that register. Interrupt 10h is the BIOS video service that actually performs the change.

color_value takes a bit of a journey to get to its final location. It’s initially written to BX, with its low byte available at BL and the high byte at BH. The low byte is duplicated into the high byte, where the BIOS call expects it. The value left in BL serves no further purpose.

When the interrupt returns, the border color has been set.

SetPaletteRegister()

The SetPaletteRegister() procedure configures the display adapter to use color_value as the screen display color at positions where the video memory contains palette_index, using a BIOS interrupt call. This maps one of the 16 available palette index values to any of the 64 color values reproducible by the display hardware. In order to program the entire palette, this procedure must be called 16 times.

The EGA display supports two classes of video modes – the 350-line modes and the 200-line modes – which are differentiated by their horizontal synchronization frequencies. “Lines” refer to the vertical graphical resolution of the screen, and all of the text modes are 350-line. The 200-line modes exist primarily for backward compatibility with CGA cards, which only support 16 colors in total. An EGA display, while technically capable of producing 64 colors, intentionally limits its color range while running in 200-line modes to avoid inaccurate color reproduction if being driven by a CGA card. Because of this compatibility feature, the color_value has a different interpretation depending on whether the display is running in a 200-line or 350-line mode.

Color values in 350-line mode:

| Bit Position | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 (least significant) | Blue (67% of output level) |

| 1 | Green |

| 2 | Red |

| 3 | Blue Intensity (33% of output level) |

| 4 | Green Intensity |

| 5 | Red Intensity |

| 6–7 (most significant) | Not used |

Note: Some sources refer to the Intensity signals as “least significant” due to their overall contribution to the output level, but this is confusing as heck from the perspective of color value bit packing and we will never say it that way here.

Color values in 200-line mode:

| Bit Position | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 (least significant) | Blue (67% of output level) |

| 1 | Green |

| 2 | Red |

| 3 | Not used |

| 4 | Intensity (33% of output level) |

| 5–7 (most significant) | Not used |

The 200-line modes contain only a single intensity signal which affects the red/green/blue channels in unison. This is also the only mode where the dark yellow-to-brown color adjustment occurs.3

The discontinuity in the bit assignments in 200-line mode makes a little more sense when the connector pinouts for the CGA and EGA displays are compared:

| Pin | CGA | EGA | Color Value Bit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | Blue | Blue | 00.....X |

| 4 | Green | Green | 00....X. |

| 3 | Red | Red | 00...X.. |

| 7 | – (Reserved) | Blue Intensity | 00..X... |

| 6 | Intensity | Green Intensity | 00.X.... |

| 2 | – (Ground) | Red Intensity | 00X..... |

The pins for red intensity and blue intensity did not carry video information on the CGA, hence the green pin must be used to carry the intensity signal in CGA compatibility mode. The consequence of this is that 200-line modes (like the mode used by this game) have canonical color value sequences from 0–7, which then skip to 16–23. Values outside of these ranges work, but the red/blue intensity bits are ignored and instead produce aliases of one of the 16 canonical colors. Palettes are explained a bit more visually on the full-screen image format page.

It’s important to remember that the default palette makes this all come together. By virtue of the way the palette colors are configured, the programmer can think of palette index bits as well as the color planes they map to as I/R/G/B color channels. If the sequence were changed or custom-mixed colors were used, this reasonable mental model would fall apart.

void SetPaletteRegister(word palette_index, word color_value)

{

_AX = (0x10 << 8) | 0x00;

_BL = palette_index;

_BH = color_value;

geninterrupt(0x10);

}

The implementation of the procedure is basically a textbook BIOS video service interrupt call. AX is a 16-bit register, and writing to it also writes to the 8-bit AH and AL registers with the high and low bytes, respectively, from AX. AH=10h is the “Set/Get Palette Registers” subfunction, AL=0h specifies that one individual palette register should be modified, BL contains the index of the register to change (0–15), and BH contains the color to program into that register (0–63). Interrupt 10h is the BIOS video service that actually performs the change.

Changes to the palette are immediate, requiring no other modifications to any video memory contents. The new color becomes visible the next time a frame is drawn to the screen.

UpdateDrawPageSegment()

The UpdateDrawPageSegment() procedure recalculates the segment address of the video memory where drawing should occur. This procedure should be called each time drawPageNumber is modified in order to compute the correct value for drawPageSegment. This is a private procedure.

void UpdateDrawPageSegment(void)

{

drawPageSegment = 0xa000 + (drawPageNumber * 0x0200);

}

The game implements two screen pages, numbered 0 and 1. Generally one of these is the “draw” page, leaving the other to be the “active” page. The active page is displayed on the screen while the draw page is updated to construct the next frame of output. Once drawing on a frame is complete, the pages swap roles and drawing begins anew on the opposite page.

When drawPageNumber is 0, the correct drawPageSegment address is A000h. When drawPageNumber is 1, drawPageSegment becomes A200h. When converted from segment:offset form, the addresses are 8 planar KiB apart, or 32 linear KiB. Each page requires 32,000 linear bytes of memory, resulting in 768 slack bytes of space between the two pages.

SelectDrawPage()

The SelectDrawPage() procedure changes the draw page to page_num and updates the memory address that subsequent drawing procedures should operate on. Although page_num can be 0–7 on a fully-upgraded EGA card, it should be 0 or 1 for this game to avoid corrupting the tile image storage area. This is essentially a convenience wrapper around UpdateDrawPageSegment().

void SelectDrawPage(word page_num)

{

drawPageNumber = page_num;

UpdateDrawPageSegment();

}

All this procedure really does is store the value from page_num into the drawPageNumber variable, then call UpdateDrawPageSegment() to recalculate the correct segment address.

SelectActivePage()

The SelectActivePage() procedure switches the actively-displayed video memory page to page_num, causing its contents to appear on the screen, using a BIOS interrupt call. Although page_num can be 0–7 on a fully-upgraded EGA card, it should be 0 or 1 for this game to avoid showing gibberish tile data on the screen. If the display is in the middle of displaying a frame, the BIOS code waits until the current frame is complete before switching to the new page.

void SelectActivePage(word page_num)

{

_AX = page_num;

_AH = 0x05;

geninterrupt(0x10);

}

The AX register receives the value from page_num, and the high bits in AH are overwritten with the value 5h. This leaves the low byte of page_num in AL. AH=5h is the video BIOS “Select Active Display Page” subfunction, and AL contains the zero-based page number that should be shown. Interrupt 10h is the BIOS video service that actually performs the change.

The BIOS code figures out what the memory address for a given page number should be based on the current video mode.

EGA_BIT_MASK_DEFAULT()

The EGA_BIT_MASK_DEFAULT() macro resets the EGA’s bit mask to its default state.

#define EGA_BIT_MASK_DEFAULT() { outport(0x03ce, (0xff << 8) | 0x08); }

The outport() call performs two byte-sized I/O writes using a single word-sized write. Port 3CEh gets the byte 8h, and port 3CFh gets the byte FFh. I/O port 3CEh is the graphics controller address register, which receives the index value 8h. This points to the “Bit Mask” parameter. I/O port 3CFh is the graphics controller data register, now pointing to that bit mask, and FFh is written there.

The bit mask is used to preserve the existing value for certain pixel positions when writes to video memory occur. Any bit position with a zero value in the bit mask is preserved. By setting this parameter to FFh, this preservation is disabled and all positions become eligible to be overwritten by subsequent write operations. Generally the bit mask is changed in drawing procedures that utilize translucency effects, and this macro ensures that the mask is in a clean state to draw non-translucent things.

EGA_MODE_DEFAULT()

The EGA_MODE_DEFAULT() macro resets the EGA’s read and write modes to their default state.

#define EGA_MODE_DEFAULT() { outport(0x03ce, (0x00 << 8) | 0x05); }

The outport() call performs two byte-sized I/O writes using a single word-sized write. Port 3CEh gets the byte 5h, and port 3CFh gets the byte 0h. I/O port 3CEh is the graphics controller address register, which receives the index value 5h. This points to the “Mode Register” parameter. I/O port 3CFh is the graphics controller data register, now pointing to the mode register, and 0h is written there.

Zero is the default value for this register in the game’s video mode, so this has the effect of resetting any changes that have been made to the graphics controller’s operating parameters. The interpretation of the bits is as follows:

| Bit Position | Value (= 0h) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 7–6 (most significant) | 00b | Not used |

| 5 | 0b | Shift Register: The meaning here is not well-documented, but this is the default state for this parameter. |

| 4 | 0b | Odd/Even: Disables this CGA compatibility addressing mode. |

| 3 | 0b | Read Mode: The processor reads data from the memory plane selected by the read map select register. |

| 2 | 0b | Diagnostic Test Mode: Disabled. |

| 1–0 (least significant) | 00b | Write Mode: Each memory plane is written with the processor data rotated by the number of counts in the rotate register, unless Set/Reset is enabled for the plane. Planes for which Set/Reset is enabled are written with 8 bits of the value contained in the Set/Reset register for that plane. |

Throughout the entire game, only the read mode and write mode are modified, so these are really the only relevant bits being reset here.

EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE()

The EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE() macro resets the EGA’s map mask to its default state and enables latched writes from the CPU.

#define EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE() { \

outport(0x03c4, (0x0f << 8) | 0x02); \

outport(0x03ce, (0x01 << 8) | 0x05); \

}

Each of the outport() calls performs two byte-sized I/O writes using a single word-sized write.

On the first write, port 3C4h gets the byte 2h, and port 3C5h gets the byte Fh. I/O port 3C4h is the sequencer address register, which receives the index value 2h. This points to the “Map Mask” parameter. I/O port 3C5h is the sequencer data register, now pointing to this map mask, and Fh is written there.

The map mask contains a four-bit value, with each bit referring to one plane of video memory. Any plane whose bit is set to “1” will be written to when the CPU writes to a video memory address, while planes with “0” bits will be unaffected by the write. Setting the map mask to Fh has the effect of permitting writes to all four video memory planes in unison. This is the default state of the EGA in the video mode used by the game.

On the second write, port 3CEh gets the byte 5h, and port 3CFh gets the byte 1h. I/O port is the graphics controller address register, which receives the index value 5h. This points to the “Mode Register” parameter. I/O port 3CFh is the graphics controller data register, now pointing to the mode register, and 1h is written there.

The interpretations of most of the bits in the mode register are the same as explained in EGA_MODE_DEFAULT(). The only difference here is the write mode, which is configured as follows:

| Bit Position | Value (= 1h) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 1–0 (least significant) | 01b | Write Mode: Each memory plane is written with the contents of the internal latches. These latches are loaded by a processor read operation. |

By configuring the mode in this way, the EGA card can leverage its internal latches (a latch is essentially a single-byte memory cell) to write pixel data to memory without requiring it to pass through the CPU. Very broadly, the latches are usually used to move solid tile data around, while direct writes are used when tiles are drawn with transparency.