Joystick Functions

Although not especially popular or even all that pleasant to use, the game has rudimentary support for player control via a joystick. This only has an effect during gameplay – a keyboard is still required to navigate the menu system and in-game dialog boxes.

It would be fair to say that the joystick support is incomplete and a bit buggy. It was possibly a late addition or afterthought, something more intended to be used as a selling point rather than a full-fledged input method. Still, it’s in there, and the hardware is interesting enough in its own right to warrant some investigation.

The IBM Game Control Adapter

Joysticks were big in video games of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Atari had a design for a digital joystick port that was relatively popular, and which eventually appeared in Commodore, Amiga, and Amstrad systems. Other manufacturers had their own incompatible designs as well, and IBM was no exception.

The IBM interface for joysticks was developed all the way back with the original PC, where a 15-pin game connector could be added to a system by way of an optional Game Control Adapter card. This connector supported four continuously-variable analog inputs and four on/off button inputs. Typically this was split into an “A” joystick and a “B” joystick, each having a set of analog X/Y axes and two buttons. (More esoteric setups used four single-axis paddles, each having one button, or some other combination.)

IBM’s game card wasn’t exactly cheap or practical. The cost in purchasing it, and the expansion slot space it occupied, were prohibitive for many. Third-party manufacturers eventually started integrating compatible game ports into multi-purpose expansion cards, combining this functionality with parallel, serial, or other expansion ports. But its popularity really took off in 1989, when Creative Labs included a game port by default on its new Sound Blaster card. In addition to game controllers, the card was also capable of interfacing with musical instruments that used the MIDI protocol. By combining waveform playback and recording, music synthesis, and joystick input on one card, the Sound Blaster quickly became a “must-have” accessory for both gamers and musicians.

Regardless of the manufacturer, all implementations of this port follow IBM’s original design: four analog channels and four button inputs, exposed through a 15-pin D-subminiature connector. Software can read the joystick state in a rather unusual way – instead of reading voltages or some other quantized representation of the analog inputs, the measurement is based on timing. This design decision made the PC’s game port one of the more interesting inputs to program for.

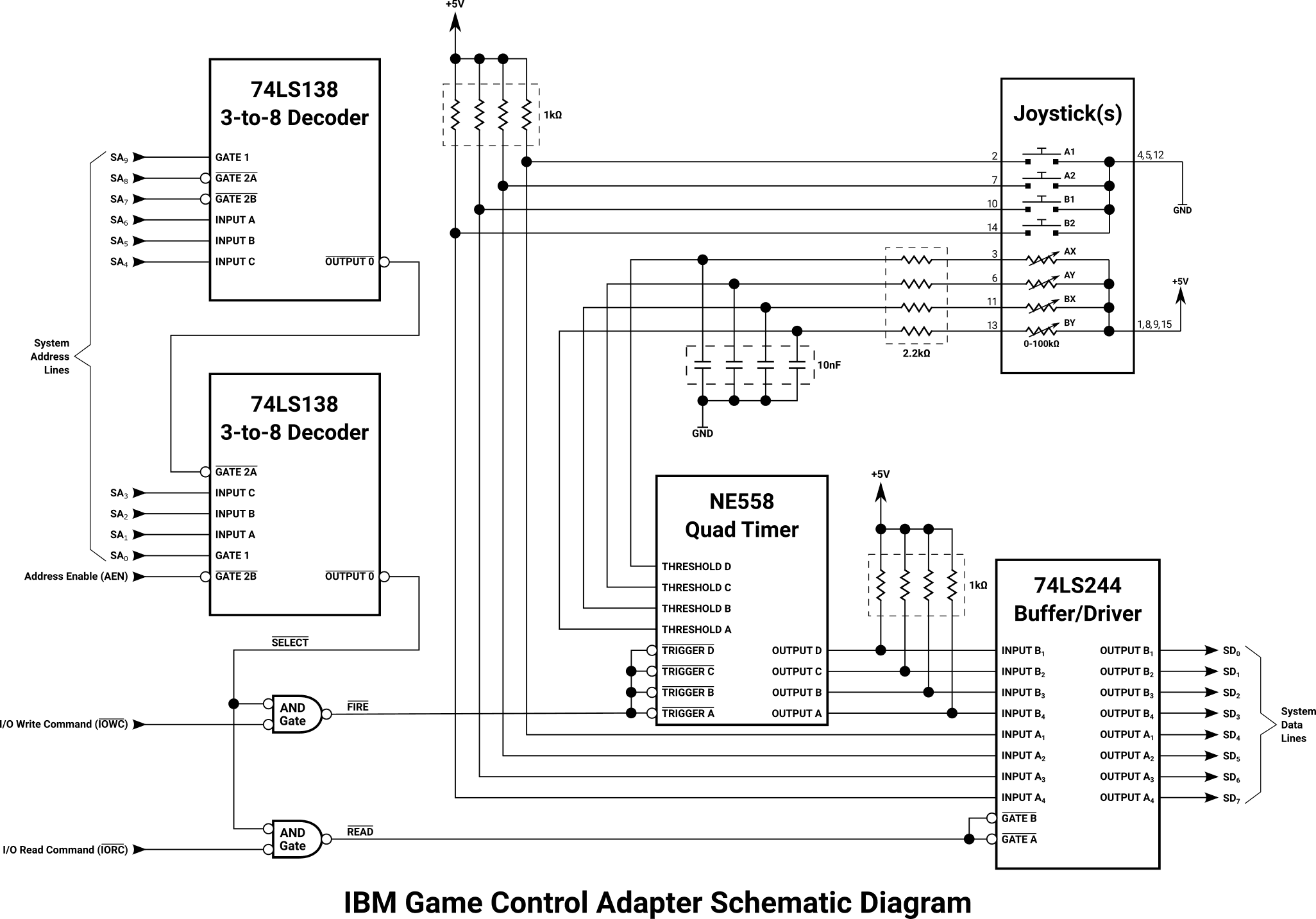

Electrically, the original Game Control Adapter was relatively straightforward:

This circuit has appeared, pretty much unmodified, in other game port implementations as well – perhaps most notably on the ISA version of the Sound Blaster card. For clarity, a few of the filter capacitors and boilerplate connections have been omitted. The complete schematic is available in the Hardware Reference Library supplement1 for the card.

The ten address lines SA0-SA9 and the Address Enable (AEN) line are decoded by a pair of 74LS138 chips. Each of these takes a three-bit binary input and activates one of eight output lines in response. (e.g. an input of 000b activates output 0; 100b actives output 4, and so on.) Each of these chips have three gate lines that control activation of the outputs. Gate 1 must be high and gates 2A and 2B must each be low for the chip to activate any of its outputs. Through clever wiring at the inputs and gates, the first chip reacts to the 20xh portion of the card’s address (201h), and the second chip reacts to 1h, a low AEN signal, and output value of the first chip. This construction activates the SELECT line whenever non-DMA I/O is occurring at address 201h.

The SELECT line is further split using a pair of 74LS32 OR gates, which function as active-low AND gates. By gating the SELECT line with IORC and IOWC, READ and FIRE signals are derived. READ is active whenever software reads from the adapter’s I/O port, and FIRE is active during writes to the I/O port.

Since the four joystick buttons only support on/off states, their section of the schematic is trivial. If the button is in the unpressed state, a 1 kiloohm (kΩ) pull-up resistor on the adapter supplies power to the line and the 74LS244 driver reads a “1” signal at its input. If the button is pressed, the joystick internally grounds the line, providing an escape path for the pull-up resistor’s power, causing the driver to read a “0”. The four button inputs are fully independent, and the corresponding driver outputs are wired to the high four bits on the 8-bit data bus. Any read from I/O port 201h returns the instantaneous status of the four buttons in the high four bits: 0 when pressed and 1 when unpressed.

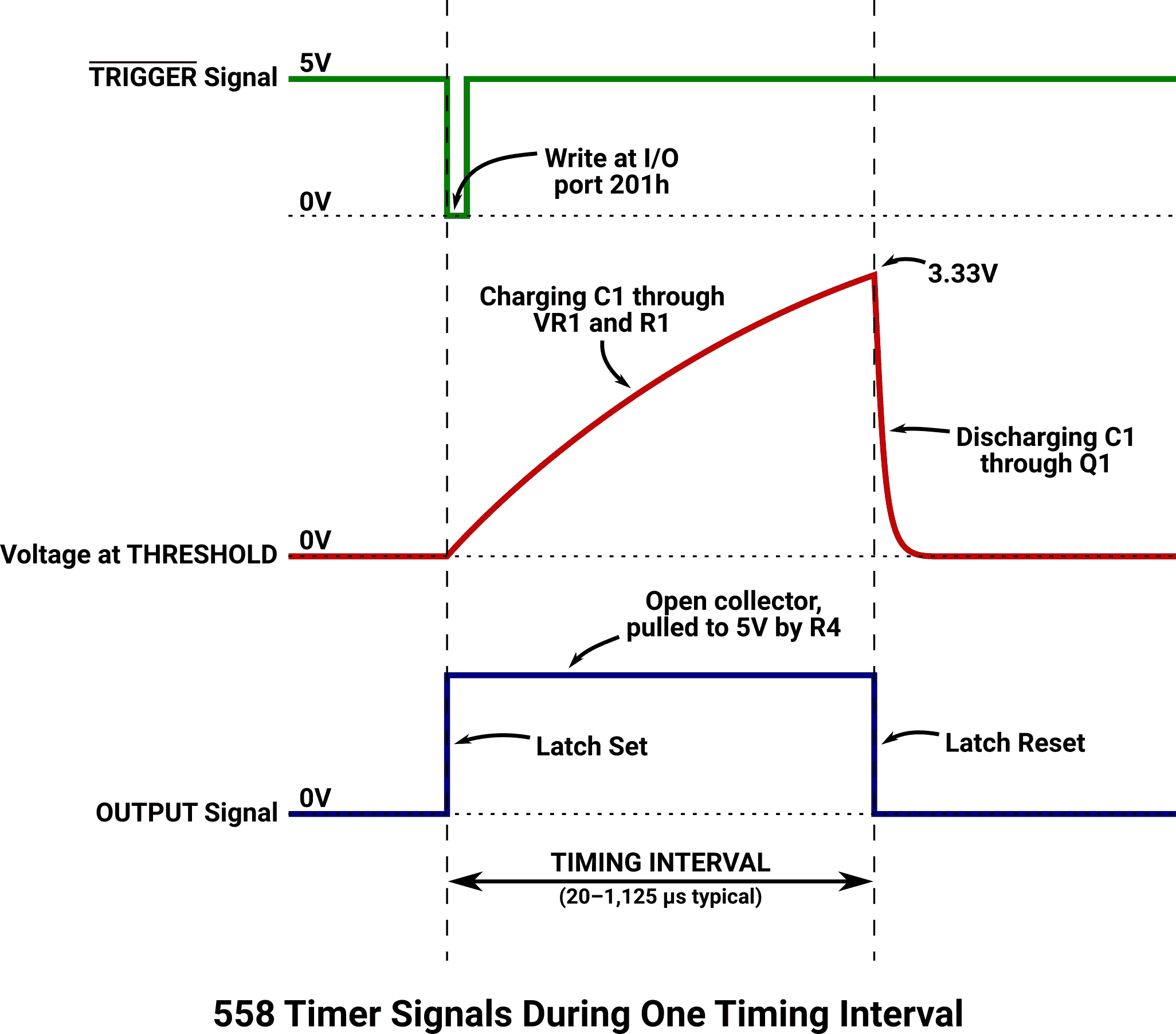

The remaining four inputs are analog. By physically changing the joystick position, the user is actually moving the contacts inside a potentiometer (sometimes called a variable resistor), changing its resistance based on position. This resistance is measured – across four independent channels – by an NE558 timer. This is a stripped-down four-channel variant of the 555 timer IC that would no doubt be familiar to anyone who has dabbled in hobby electronics. As the resistance changes, the length of the timing interval changes, and this lengthens or shortens the amount of time the 558’s output lines stay in the active state. These outputs are connected to the lower four inputs on the 74LS244 driver, and become readable to the software through the low four bits on the 8-bit data bus. When I/O port 201h is read, the instantaneous status of the timer outputs is returned in the low four bits: 0 if the timing interval is complete and 1 while it is still running.

Writing to I/O port 201h triggers a new timing interval on all four timer channels. The actual value written is ignored entirely; it is the mere act of writing that is significant.

Journey to the Center of the 558 Timer IC

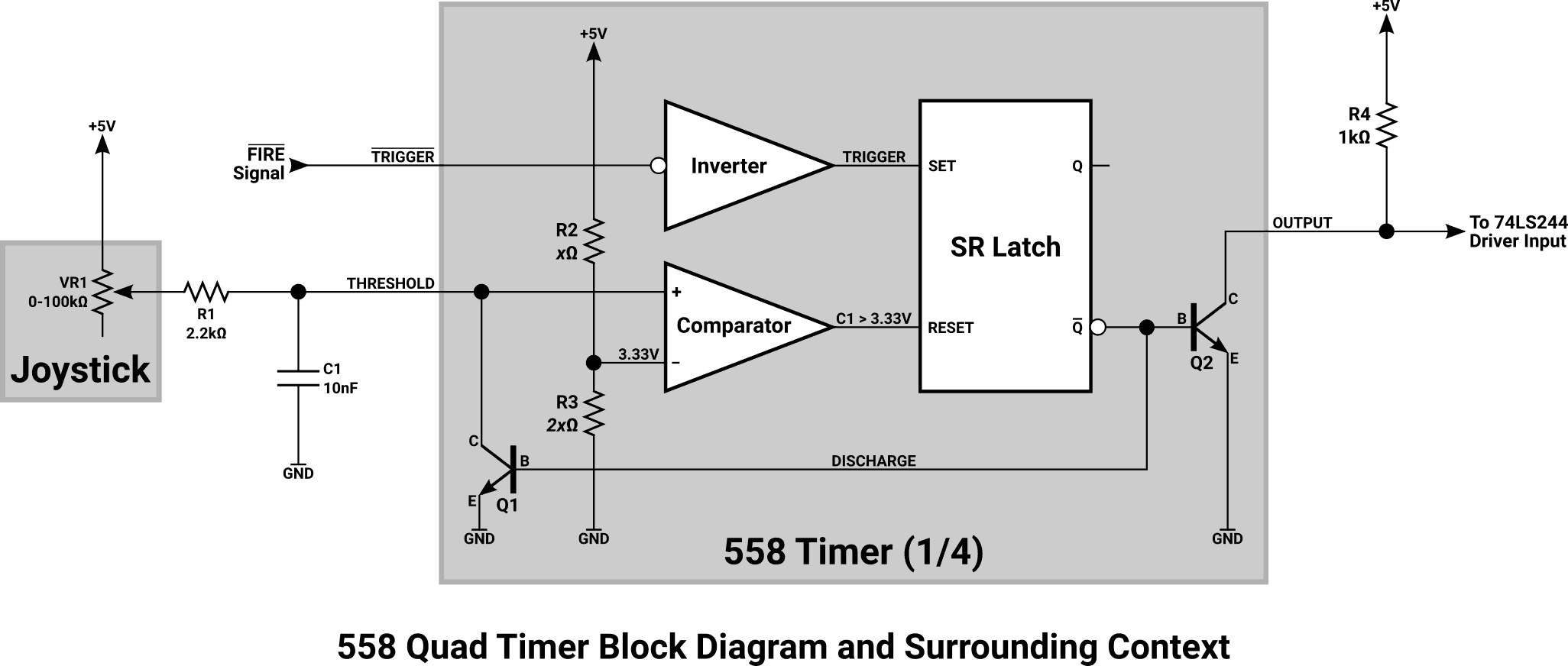

This translation from position to resistance to time to boolean on/off warrants a bit more investigation. Luckily the 558 and its surrounding context is actually simple enough to understand, at least in its block diagram form:

Note: Only one channel is pictured here, and for clarity the “reset” and “control voltage” pins on the chip aren’t included since the Game Control Adapter doesn’t do anything interesting with them.

The FIRE line is activated briefly whenever a write occurs on the adapter’s I/O port. This line carries what’s called an “active low” signal. This means that when the signal is conceptually “active,” the voltage is low – at or near zero volts. High voltage, at or near 5 volts, is considered “inactive.” These types of signals are represented by an overline in text, or as unfilled dots on components in the schematic.

The FIRE signal enters the 558 timer on its TRIGGER pin, where it enters an inverter (sometimes called a NOT gate) that flips the signal into “active high” form. This is the more familiar arrangement where high voltage is considered “active” while low voltage is “inactive.” From there, the TRIGGER signal enters the “set” input of a set/reset latch.

A set/reset (SR) latch can be thought of as an on/off switch with two separate buttons. Pressing the “set” button turns the latch on, and pressing “reset” turns it off. Pressing “set” while the latch is already on (or “reset” while it’s off) causes no change in state. The latch’s output is exposed on a line called Q, and the inverse of this output is exposed on Q.

Note: Pressing both “set” and “reset” at the same time puts the latch into a nonsense state where the outputs become meaningless. Don’t do that.

An active TRIGGER signal turns the latch on, which immediately brings the Q and Q lines active. (Eventually the I/O write operation completes, deactivating the TRIGGER signal, which has no effect on the state of the latch.) The Q output is unused, while Q, now carrying zero volts, feeds the “base” input on a pair of transistors.

The transistors in this application are simple switches. When voltage is presented at the base input, current is allowed to flow from the collector out to the emitter. If there is insufficient voltage at the base, this collector-emitter flow is inhibited. Since both transistors here are seeing zero volts at their base inputs, no current flows through them. Through transistor Q2’s collector, this becomes the state of the OUTPUT pin – it neither sources nor sinks current from the rest of the circuit. This is called an open collector arrangement, since an inactive signal is in a state that is neither high nor low.

The 74LS244 driver, which receives the output of this timer, cannot work with an open collector signal. To compensate for this, a 1 kΩ pull-up resistor (R4) is employed to pull the open output high. This ultimately causes the “1” signal that the software reads through the driver while the timer is running.

Now that the timer is armed and timing, we need to actually measure the joystick position somehow. The Game Control Adapter supplies five volts DC to the joystick, which is fed into the VR1 potentiometer that is physically connected to the joystick handle. As the user moves the handle around, a wiper is dragged across a resistive substrate, changing the amount of resistance between the edge of the substrate and the wiper’s contact. The substrate is connected to the five volt supply, and the wiper is connected to the X or Y axis input pin going back to the Game Control Adapter. As the joystick is moved, the resistance across the connector’s pins changes from about 0 Ω (at the top or left corners) to around 100 kΩ (at the bottom or right corners). These values are not precise, and there is a great deal of variance between different joysticks, but this is the approximate range.

Once the signal enters the Game Control Adapter, it runs through a 2.2 kΩ resistor (R1) which increases the absolute minimum resistance of the circuit. Finally the signal finds its way into a 10 nanofarad (nF) capacitor (C1) whose other terminal is tied to ground. This creates a charging circuit, where current flows from the supply through VR1, R1, C1, and back to ground. This slowly charges C1 like a battery.

When resistor(s) and a capacitor are combined in series like this, it is called an RC circuit. These circuits have the useful property that the charge rate of a capacitor (in seconds) can be predicted by multiplying the total resistance in ohms by the capacitance in farads:

| VR1 | R1 | C1 | Time Constant (VR1 + R1) × C1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 Ω (top/left) | 2.2 kΩ | 10 nF | 22 µs |

| 25 kΩ | 2.2 kΩ | 10 nF | 272 µs |

| 50 kΩ (centered) | 2.2 kΩ | 10 nF | 522 µs |

| 75 kΩ | 2.2 kΩ | 10 nF | 772 µs |

| 100 kΩ (bottom/right) | 2.2 kΩ | 10 nF | 1.022 ms |

Assuming ideal and precise components, each time constant describes the amount of time it takes the circuit to charge the capacitor to 63.2% of the supply voltage. This rather arbitrary-seeming value is due to the logarithmic behavior of a charging capacitor: Voltage climbs rapidly at the start of the charge, but the rate tapers off substantially after the capacitor is charged about ⅔ of the way. (The formal derivation for this constant is 1 - e-1.) Not every implementation uses these component values – some sources have reported C1 sizes as low as 5.6 nF or as high as 22 nF, which can nearly halve or double the charge times as calculated here. Fortunately the change in timing always corresponds linearly to the change in joystick position, so the calculations do not require any complicated transformations once the ratio has been determined.

Note: The IBM publication specifies 24.2 + 0.011(r) as the function to convert ohms into microseconds, while our computed ratio is 22 + 0.01(r). IBM’s values are probably more correct as they undoubtedly tested them on real hardware instead of a phone calculator.

As the capacitor C1 charges, the voltage as measured between R1 and C1 climbs. This voltage is fed into the 558 chip on the THRESHOLD pin, where it enters the “+” input on a device called a comparator.

A comparator is a special form of operational amplifier (“op amp”) that measures voltage on two inputs named “+” and “-”. If the voltage on “+” is higher than the voltage on “-”, the comparator’s output is active. If “+” has lower voltage than “-”, the output is inactive. This particular “+” input is measuring the charge on C1, which started at zero volts and is climbing as the charge grows.

The comparator’s “-” input is fed from a pair of resistors which form a voltage divider. A voltage source of five volts enters a resistor (R2) with a resistance value of x Ω. The absolute value is not actually important; only resistance ratios matter here. Another resistor (R3), with a resistance of 2x Ω, completes the path to ground. The voltage as measured between these two resistors is 5 × 2x / (x + 2x) or 3.33 volts. This provides a constant 3.33 volt signal on the comparator’s “-” input, which has the effect of keeping the comparator’s output inactive while the capacitor C1 holds a charge below 3.33 volts, and bringing the output active as soon as the C1 voltage rises above this 3.33 volt threshold.

The fact that the RC constant is 63.2% while the voltage divider output is 66.7% is an intentional, useful, and simple approximation.

The comparator’s output is fed into the “reset” input of the SR latch we described earlier. This causes the latch to reset once C1 reaches its 3.33 volt threshold, deactivating the output lines. This in turn places five volts on the Q line, which activates the base inputs on transistors Q1 and Q2 and turns both of them on.

When Q2 turns on, it connects its collector and emitter lines, providing a path to ground at the OUTPUT pin of the 558. This sucks away everything provided by the R4 pull-up resistor, leaving a low signal to be read by the 74LS244 driver input. This causes a “0” to be read from the I/O data bus, signaling that the timing interval has ended. The Q1 transistor is also turned on now, which provides a path to ground at the THRESHOLD pin of the 558. This rapidly drains the charge held by C1, bringing it back down to near zero volts.

At this point, the timer has completed one full cycle and is ready for another activation signal from the FIRE line, at which point the entire process will repeat itself.

Calibration and Slop

In order to interface with this timing paradigm, the software must trigger the FIRE line, observe the “1” bit in the timer’s output, and then repeatedly poll the output until the output bit returns to “0.” The polling frequency must be high enough to discern timing derivations of 22 µs or less, which is the length of the timing interval at the top/left limit of the joystick’s travel.

The timing accuracy is affected by a number of things. The choice of resistance values in the joystick, the adapter card, and inside the 558 timer itself can all affect the charge rate, as well as variance in the capacitor itself. Many consumer-grade electronic components can only deliver accuracy within ±10%, and the resistance values can change based on ambient temperature. There is no guarantee that timing intervals measured on one channel of one system at one point in time can provide any acceptable degree of accuracy in any other context. This was really the classic lament of joystick programming.

This is why practically every game designed for the PC requires the user to go through some kind of joystick calibration procedure, where the software requests the user to move the joystick through its maximum range of travel while it observes the extents of the timing intervals that are produced. Since these measurements would be useless on any other machine (or in some cases, useless on the same machine if the room temperature changed enough) most programs never bothered to persist the calibration values to disk.

In this game’s case, the calibration procedure asks the user to place the joystick in the top left corner, followed by the bottom right, to simultaneously capture the minimum intervals across both axes followed by the maximum intervals. The user is required to do this every time the game starts before it will even consider reading game input from the joystick.

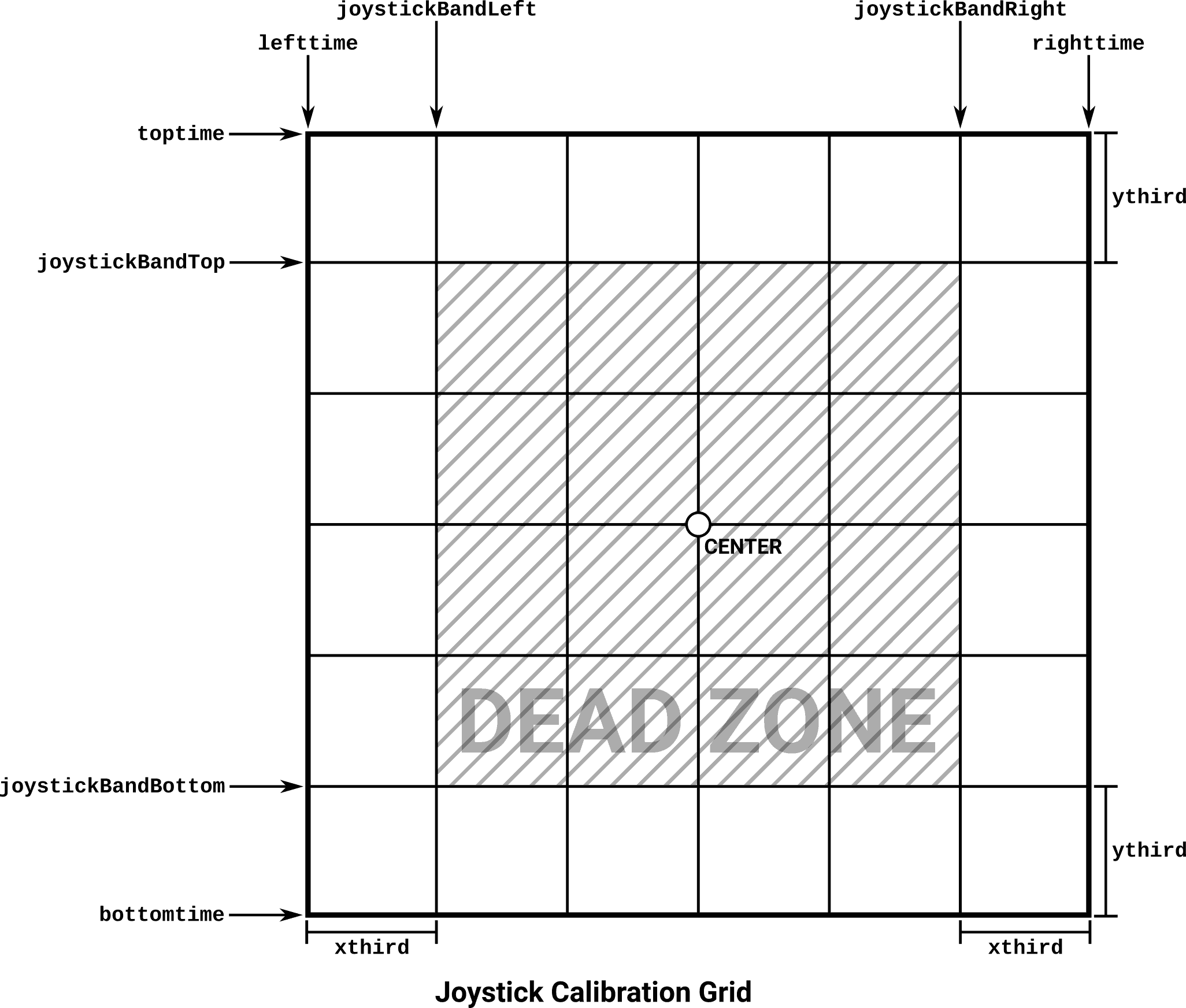

The analog inputs of the joystick are infinitely variable, subject to the polling resolution of the software. The game’s input, by comparison, is boolean – there is only one speed in each direction, which can be either on or off with no in-between. The joystick input is translated into this on/off scheme by dividing the joystick’s travel area into a 6×6 grid. If the stick is in the outer band of this grid (e.g. more than ⅔ from center position) the direction is considered to be active. This creates a generous safety margin around the joystick’s center position to keep small “wobbles” from unintentionally moving the player.

ShowJoystickConfiguration()

The ShowJoystickConfiguration() function prompts the user to calibrate the joystick timings and button configuration for the joystick identified by stick_num. It can be accessed from the “Game Redefine” menu in either the main menu or the in-game help menu. This function must run to completion for isJoystickReady to become true. If a key is pressed at any point, the function is aborted.

Note: Since this menu may be displayed during the game, it is important that it only draws in front of the scrolling gameplay area. Any tiles drawn over the status bar or black border will persist after the menu is dismissed.

This function bears a striking similarity to CalibrateJoy()2 from Id Software’s C Library as used in Hovertank 3-D.

void ShowJoystickConfiguration(word stick_num)

{

word xframe;

word junk;

word xthird, ythird;

int lefttime, toptime, righttime, bottomtime;

byte scancode = SCANCODE_NULL;

JoystickState state;

This function uses a relatively large number of local variables:

xframe: The screen X coordinate of the inner left edge of the UI frame as returned byUnfoldTextFrame(). This is used to position the text lines within the frame.junk: Serves no useful purpose, but is included in the reconstruction to keep the stack variables and instruction sequences accurate to the original game. In the Hovertank 3-D source,2 this was calledstageand it was used to animate an eight-frame spinning arrow cursor after each text prompt.xthirdandythird: For each of the X and Y axes, this represents the expected change in timing length when the joystick handle is moved one-third of the distance between its center position and one of the edges.lefttime: The length of the timing interval seen on the X channel when the joystick was at its leftmost position.toptime: The length of the timing interval seen on the Y channel when the joystick was at its topmost position.righttime: The length of the timing interval seen on the X channel when the joystick was at its rightmost position.bottomtime: The length of the timing interval seen on the Y channel when the joystick was at its bottommost position.scancode: Holds a copy of the most recent byte that was sent from the keyboard. This value is explicitly zeroed to start.state: AJoystickStatestructure containing the state of the two joystick buttons.

The stick_num value should be either JOYSTICK_A or JOYSTICK_B to select that joystick. The game only implements JOYSTICK_A, and this is the only value that will work correctly.

xframe = UnfoldTextFrame(3, 16, 30, "Joystick Config.",

"Press ANY key.");

UnfoldTextFrame() presents a 30x16 tile frame that provides the background for this interaction. The top value of 3 ensures that the frame does not draw over the in-game status bar if this menu is shown during the game.

while ((lastScancode & 0x80) == 0) ;

do {

state = ReadJoystickState(stick_num);

} while (state.button1 == true || state.button2 == true);

The first while loop runs until lastScancode, the most recent scancode byte sent by the keyboard, is a break code. This causes the game to wait until the most recently pressed key (most likely the J that the user pressed to get into this menu) has been released.

The do…while loop continually polls the joystick hardware via ReadJoystickState() until both buttons are released. This ensures that any subsequent button presses are intentional prompt responses.

DrawTextLine(xframe, 6, " Hold the joystick in the");

DrawTextLine(xframe, 7, " UPPER LEFT and press a");

DrawTextLine(xframe, 8, " button.");

junk = 15;

do {

if (++junk == 23) junk = 15;

ReadJoystickTimes(stick_num, &lefttime, &toptime);

state = ReadJoystickState(stick_num);

scancode = StepWaitSpinner(xframe + 8, 8);

if ((scancode & 0x80) == 0) return;

} while (state.button1 != true && state.button2 != true);

DrawTextLine() instructs the user to hold the joystick in the upper left corner. This has the effect of setting both axes’ variable resistors to their minimum possible values.

junk is junk. In Hovertank 3-D, where this code apparently originally came from, this was passed to their DrawChar() function to create an eight-frame spinner effect at the end of the prompt. The value starts at 15, increments eight times, and then goes back to 15 to repeat. It’s never used again here, making it more of a curiosity than anything else.

In a do…while loop, ReadJoystickTimes() polls the joystick hardware, and returns the length of the current X timing interval in lefttime and the Y in toptime. These values are continually rewritten as the loop iterates.

ReadJoystickState() captures the current state of the joystick buttons.

StepWaitSpinner() draws the next frame of the wait spinner, positioned at the end of the prompt text, then returns the most recent byte that was returned by the keyboard controller. It does not wait for input, so it is appropriate to use within this loop.

The loop has two termination conditions. If the most recent scancode returned by StepWaitSpinner() was a make code, a key is now down that wasn’t down before. The game interprets this as a request from the user to abandon the joystick configuration process, which is done with a return. The loop can also terminate if either of the joystick buttons become pressed, as the prompt instructed the user to do. If this happens, execution continues and the values currently held in lefttime and toptime become final. Since the joystick is being held in its upper-left corner, these values should be the leftmost and topmost timings that are ever returned by this joystick on this system.

EraseWaitSpinner(xframe + 8, 8);

WaitHard(160);

do {

state = ReadJoystickState(stick_num);

} while (state.button1 == true || state.button2 == true);

The prompt responds to the user’s action by erasing the wait spinner with EraseWaitSpinner() and delaying for a little over one second with WaitHard(160). A small portion of this delay is essential to “debounce” the button input, which suppresses any transitory on/off signals that may be read while the button is being released.

The loop waits until both joystick buttons are released again, the same way as when the function was first entered.

DrawTextLine(xframe, 10, " Hold the joystick in the");

DrawTextLine(xframe, 11, " BOTTOM RIGHT and press a");

DrawTextLine(xframe, 12, " button.");

do {

if (++junk == 23) junk = 15;

ReadJoystickTimes(stick_num, &righttime, &bottomtime);

state = ReadJoystickState(stick_num);

scancode = StepWaitSpinner(xframe + 8, 12);

if ((scancode & 0x80) == 0) return;

} while (state.button1 != true && state.button2 != true);

This is pretty much an exact duplicate of the code from earlier, only now the user is being instructed to place the joystick handle in the bottom right position and the values are being stored in righttime and bottomtime.

EraseWaitSpinner(xframe + 8, 12);

do {

state = ReadJoystickState(stick_num);

} while (state.button1 == true || state.button2 == true);

As before, the wait spinner is erased and execution is paused until both joystick buttons are released again. This does not impose an artificial wait like the previous prompt did.

xthird = (righttime - lefttime) / 6;

ythird = (bottomtime - toptime) / 6;

joystickBandLeft[stick_num] = lefttime + xthird;

joystickBandRight[stick_num] = righttime - xthird;

joystickBandTop[stick_num] = toptime + ythird;

joystickBandBottom[stick_num] = bottomtime - ythird;

Here, the calibration values are actually processed into something the game can use. In a properly designed joystick, the left/top positions should have the lowest resistance and thus the shortest timing intervals. The right/bottom positions would then be the longest. The length of the timing interval changes linearly with the position of the joystick handle, so it is possible to divide the joystick’s travel range into roughly equal sections:

xthird and ythird are calculated to be one-third of the distance from the stick’s center position to one of the edges. These values are used, relative to the minimum and maximum timing values seen during the calibration process, to set the boundary between the “dead zone” where movement is ignored, and the outer band where the movement is honored. The stick needs to be moved ⅔ of the way to an edge (relative to center position) for a move to register.

These timing boundary values are stored in joystickBandLeft[], joystickBandRight[], joystickBandTop[], and joystickBandBottom[]. These variables are each indexed by stick number, even though multiple joystick support is not implemented.

DrawTextLine(xframe, 14, " Should button 1 (D)rop");

DrawTextLine(xframe, 15, " a bomb or (J)ump?");

scancode = WaitSpinner(xframe + 19, 15);

if (scancode == SCANCODE_ESC) {

return;

} else if (scancode == SCANCODE_J) {

joystickBtn1Bombs = true; /* BUG: Bomb/Jump buttons are swapped */

} else if (scancode == SCANCODE_D) {

joystickBtn1Bombs = false; /* BUG: Bomb/Jump buttons are swapped */

} else {

return;

}

The final prompt asks the user how they would like the buttons to be configured. The joystick has two buttons, conventionally numbered “1” and “2”, which can be assigned to the player’s “jump” and “drop bomb” actions.

The call to WaitSpinner() blocks until any make code is received from the keyboard, at which point the scancode is returned in scancode. If the Esc key (or any unexpected key) was pressed, the function returns early. If either J or D were pressed, joystickBtn1Bombs is set with the player’s wishes. There is a rather blatant bug here – the behavior for “jump” and “bomb” is handled backwards, meaning the user has to enter the opposite choice from what they actually want to see in the game.

Opposite Day

I can see two ways this bug may have occurred. The first possibility is that the original variable name for

joystickBtn1Bombswas something like “swap buttons” and the author(s) working on the other parts of the code forgot what “swapped” and “not swapped” meant in the absolute sense.The other possibility is that maybe someone lost track of the fact that joystick buttons are one-based, and figured that the button opposite to “1” was “0” instead of “2” and that messed up their reasoning about which button was the primary. As I write it out, this scenario seems less and less plausible.

Whatever the reason, it’s frankly inexcusable that this bug made it past QA.

Having collected all of the input needed, the function prepares to return.

isJoystickReady = true;

}

The function ends by setting isJoystickReady true, which permits joystick movement to actually influence the player’s movement. This is the only place in the entire game where this is enabled, which forces the user to complete the entire calibration procedure any time they wish to (re)activate the joystick.

With this done, the function returns quietly.

ReadJoystickTimes()

The ReadJoystickTimes() function triggers a timing interval on the joystick hardware, and returns the raw interval lengths for the one joystick, identified by stick_num, in x_time and y_time.

This function is basically identical to ReadJoystick()3 from Id Software’s C Library as used in Hovertank 3-D.

void ReadJoystickTimes(word stick_num, int *x_time, int *y_time)

{

word xmask, ymask;

if (stick_num == JOYSTICK_A) {

xmask = 0x0001;

ymask = 0x0002;

} else { /* JOYSTICK_B */

xmask = 0x0004;

ymask = 0x0008;

}

The provided stick_num value is decoded into mask bits. The first joystick stores its X and Y timer status in bits 0 and 1, respectively. The second joystick (which is fully implemented within this function) uses bits 2 and 3 for the timer status. The mask values are stored in xmask and ymask.

*x_time = 0;

*y_time = 0;

outportb(0x0201, inportb(0x0201));

x_time and y_time are the return values for this function, provided by the caller as a pair of pointers. They are zeroed to begin with.

The game control adapter’s I/O address is 201h. The call to inportb() reads the current status of the timers and buttons from the adapter, and that value is immediately written back with outportb(). The actual value written is meaningless – the game control adapter does not contain any circuitry that is capable of reading the data bus during a write operation. The mere act of writing, which activates the adapter’s IOWC line, is all that is needed to activate the timers. inportb() and its return value are pointless here.

At this point in execution, both timers should be reporting a 1 bit as their capacitors start to charge.

do {

word data = inportb(0x0201);

int xwaiting = (data & xmask) != 0;

int ywaiting = (data & ymask) != 0;

*x_time += xwaiting;

*y_time += ywaiting;

if (xwaiting + ywaiting == 0) break;

} while (*x_time < 500 && *y_time < 500);

}

The remainder of the function is a polling loop. It begins by reading the status byte from the game control adapter with an inportb() from I/O port 201h. The xmask and ymask values are applied to isolate just the relevant axis bit for the chosen joystick. xwaiting and ywaiting will each hold a 1 value while the timer is running. Once a timer completes its timing interval, either xwaiting or ywaiting will flip to 0.

During each iteration of the polling loop, both x_time and y_time are incremented by the values in xwaiting and ywaiting. The increment-by value will be either 0 or 1, depending on whether or not the timing interval for that axis has completed.

Next is the happy path test for polling completion: If xwaiting and ywaiting are both zero, this means that both timers have finished their timing intervals and no further polling is needed. The values currently held in x_time and y_time are final, and the function can return.

Otherwise, a fail-safe check is performed: If either x_time or y_time have gone 500 iterations without the timing interval finishing, further polling is aborted. Either the resistance in the joystick is too high, something became unplugged, or the polling loop is running too fast. Regardless of the reason, it’s safer to return a half-baked value than to get stuck in this loop.

Note:

The polling loop is not synchronized to anything that could reliably be called a real-time clock. It runs as fast or as slow as the processor permits it to. There is a bit of a governing factor in the call to

inportb(), since an AT-compatible bus should never run faster than about 8 MHz and it takes a 286 processor five bus cycles to move data in from the adapter. This provides an upper bound on how many I/O reads the system should be able to do in any given period of time. But older PCs run their bus clock at the same speed as the processor. 4.77, 6, 8 MHz, or really anything.To further complicate things, this function does not suspend interrupt processing. Any time the CPU spends servicing an interrupt is time spent away from incrementing these counters, which can skew the results over time.

All this is to say, the scheme is only effective because the timing characteristics during calibration match the in-game environment. The absolute timing values can and will be different on other systems.

The do…while loop continues until either termination condition is reached, at which point the function returns. The caller can read the timing values from the x_time and y_time pointers it originally provided.

ReadJoystickState()

The ReadJoystickState() function polls the joystick identified by stick_num for its current position and button state, and updates the player control variables accordingly. It returns a JoystickState structure holding the current state of the buttons (but not the X/Y position).

This function is a modified version of ControlJoystick()4 from Id Software’s C Library as used in Hovertank 3-D. Their function returns the movement direction as a member of the returned JoystickState structure, but this game’s implementation modifies the player variables directly and leaves the direction member in the return value uninitialized.

JoystickState ReadJoystickState(word stick_num)

{

int xtime = 0, ytime = 0;

int xmove = 0, ymove = 0;

word buttons;

JoystickState state;

ReadJoystickTimes(stick_num, &xtime, &ytime);

This function defines a few local variables:

xtime: The number of polling cycles that completed before the joystick’s X-axis timing interval ended.ytime: The number of polling cycles that completed before the joystick’s Y-axis timing interval ended.xmove: A value between -1 and 1 to partition the joystick’s horizontal range into left/center/right zones.ymove: A value between -1 and 1 to partition the joystick’s vertical range into top/center/bottom zones.buttons: Holds the status bits that reflect the pressed/unpressed condition of each joystick button.state: AJoystickStatestructure holding the button states in a more well-defined format; returned to the caller when this function returns.

The stick_num value should be either JOYSTICK_A or JOYSTICK_B to select that joystick. The game only implements JOYSTICK_A, and this is the only value that will work correctly.

The call to ReadJoystickTimes() polls the joystick hardware for the current X- and Y-axis interval timings for joystick stick_num. The timing values are returned in xtime and ytime.

if ((xtime > 500) | (ytime > 500)) {

xtime = joystickBandLeft[stick_num] + 1;

ytime = joystickBandTop[stick_num] + 1;

}

This code is a bit odd for two reasons. Firstly, it’s using a bitwise OR to combine the results of two boolean tests. The behavior ends up being correct due to the fact that boolean zero/nonzero values compute correctly, but this was definitely a head-scratcher during disassembly.

Secondly, neither xtime nor ytime can ever be greater than 500. These variables are set inside a loop (see ReadJoystickTimes()) that aborts whenever either value reaches 500. There’s no way for them to increment beyond 500, meaning this condition is never true.

If we assume that this condition could happen, the effect would be to fudge both timings to just inside the upper-left corner of the joystick’s dead zone. The end result would be “no movement” – same as if the joystick were naturally centered.

if (xtime > joystickBandRight[stick_num]) {

xmove = 1;

} else if (xtime < joystickBandLeft[stick_num]) {

xmove = -1;

}

if (ytime > joystickBandBottom[stick_num]) {

ymove = 1;

} else if (ytime < joystickBandTop[stick_num]) {

ymove = -1;

}

The calibration values are considered here, changing the analog inputs into “go”/“no-go” determinations for each axis. xmove is 1 at the right position, -1 at left, and 0 near the center. Likewise, ymove is 1 at the bottom position, -1 at top, and 0 near the center.

cmdWest = false;

cmdEast = false;

cmdNorth = false;

cmdSouth = false;

switch ((ymove * 3) + xmove) {

case -4:

cmdNorth = true;

cmdWest = true;

break;

case -3:

cmdNorth = true;

break;

case -2:

cmdNorth = true;

cmdEast = true;

break;

case -1:

cmdWest = true;

break;

case 1:

cmdEast = true;

break;

case 2:

cmdWest = true;

cmdSouth = true;

break;

case 3:

cmdSouth = true;

break;

case 4:

cmdEast = true;

cmdSouth = true;

break;

}

The input is translated into the game’s player control variables cmdWest, cmdEast, cmdNorth, and cmdSouth. These are all set to false to start, which holds the player in a stationary position.

The control value of the switch statement is an ad hoc 3×3 grid in Y-major order with (0, 0) in the center. This clever arrangement linearizes the possible xmove and ymove combinations into a scalar value between -4 and 4. These values correspond to the eight possible input directions, or zero when stationary. The various player control variables are enabled accordingly for each possible direction.

Note: There is a bug in this code. At no point is the state of the

blockMovementCmdsvariable considered, which (under keyboard input) would cancel any inputs incmdWest,cmdEast, andcmdJump. This can allow a joystick-controlled player to walk or jump out of certain situations that a keyboard-controller player would not be allowed to.

buttons = inportb(0x0201);

if (stick_num == JOYSTICK_A) {

cmdJump = state.button1 = ((buttons & 0x0010) == 0);

cmdBomb = state.button2 = ((buttons & 0x0020) == 0);

}

With movement done, the buttons state is handled next. This necessitates another inportb() call, as nothing up to this point preserved the button state in any variable that can be accessed here.

The button states for JOYSTICK_A are in bit positions 4 and 5, which are read through a bit mask. If either bit holds a zero value, that button is currently pressed and the necessary state member takes a true value. The player control variables cmdJump and cmdBomb are also set to match.

Joystick “B” is not implemented, and there is no provision to read its button states here.

if (joystickBtn1Bombs) {

buttons = state.button1;

cmdJump = state.button1 = state.button2;

cmdBomb = state.button2 = buttons;

}

If the user requested it (actually, due to the bug in ShowJoystickConfiguration(), if the user did not request it) with joystickBtn1Bombs, the buttons are swapped here. The buttons variable is repurposed to preserve button 1 while the state members, cmdJump, and cmdBomb switch values.

return state;

}

The function ends by returning the JoystickState structure in state to the caller. This holds the current state of the two buttons, but nothing about joystick position or player control.

http://www.minuszerodegrees.net/oa/OA - IBM Game Control Adapter.pdf ↩︎

CalibrateJoy(): https://github.com/FlatRockSoft/Hovertank3D/blob/master/IDLIBC.C#L64 ↩︎ ↩︎ReadJoystick(): https://github.com/FlatRockSoft/Hovertank3D/blob/master/IDLIBC.C#L376 ↩︎ControlJoystick(): https://github.com/FlatRockSoft/Hovertank3D/blob/master/IDLIBC.C#L441 ↩︎