LZEXE

The EXE files for episodes one and two were compressed before publication. The utility used to compress these files was LZEXE version 0.91, written by Fabrice Bellard. If that name sounds familiar, it may be because Bellard later went on to create projects like FFmpeg (a multimedia file conversion suite) and QEMU (a hardware emulator).

In his own words:

LZEXE was the first wide known executable file compression for PCs under MSDOS. It allowed the MSDOS executables (.EXE or .COM files) to be compressed and then launched without having to decompress them explicitly.

I wrote LZEXE in 1989 and 1990 when I was 17. At that time, hard disks were small and expensive, and 5" floppies were small (360K). Since I had only two floppy drives on my PC (an Amstrad PC1512), saving space was really an issue.

Although I wrote LZEXE for my own use, I gave it to some friends, and it was then put on some BBS’s. LZEXE became then very famous, although I did not do anything to promote it. This success was quite unexpected for me.

—Fabrice Bellard, LZEXE Home Page 1

LZEXE was unique because it immediately launched the program once it had been decompressed. Most other compression/packing utilities required an additional step (and often additional space) to do this. Performance was very good, roughly halving the sizes of common EXE files with an almost imperceptible load delay on even the most modest computers of the day.

The compression engine was built around the Lempel-Ziv-Storer-Szymanski algorithm (LZSS), and the decompressor operated in-place – overwriting the compressed memory contents with decompressed program data as it worked – without using any more memory than the final decompressed program required. This was more difficult than it may seem at first, because the compressor had to ensure that there was never a point in time where the decompressed data began to overwrite an unread portion of the compressed data.

On top of all that, the decompression code is only 163 instructions long and fits in 330 bytes of memory.

Loading and Bootstrapping

An LZEXE-compressed program is a standard DOS executable, loaded in the standard way without any special trickery:

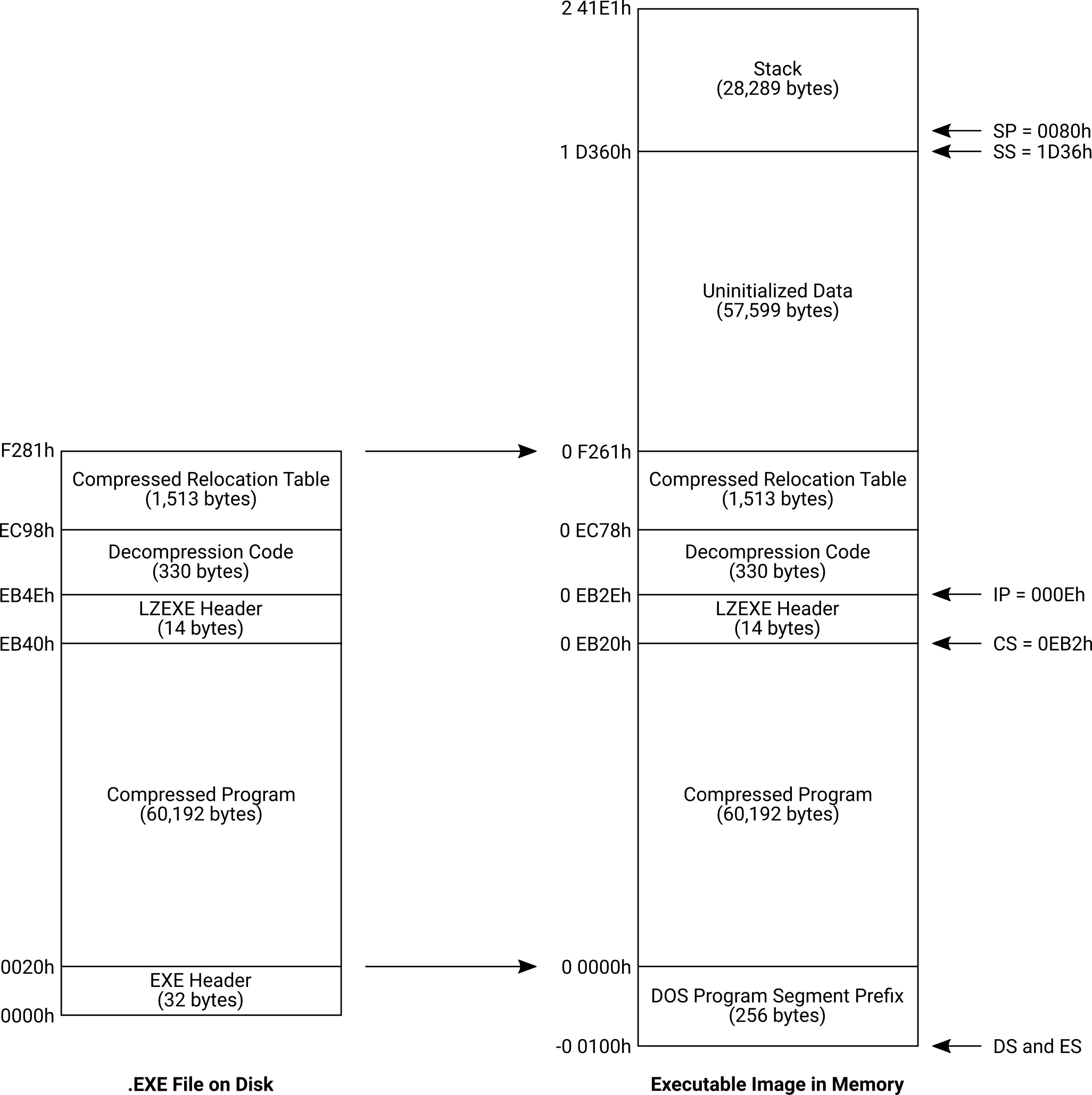

Note: The sizes and offsets in these diagrams and discussion are accurate for the first episode’s EXE file, but will be different for virtually every other program in the wild. For simplicity’s sake, I made the choice to construct the memory map as if the EXE file were loaded at address 0h with the PSP at imaginary address -100h. In reality the EXE file could be loaded anywhere in memory, and the addresses would all be adjusted relative to that.

When DOS executes the EXE file, the entire contents (minus the EXE header) are copied from the disk file directly into a free spot in memory without any modification. In our example, this occupies 62,049 bytes of memory. The EXE header specifies that an additional 85,888 bytes of memory must be allocated on top of that, which brings the total in-memory size of the load image to 147,937 bytes.

DOS constructs a Program Segment Prefix (PSP), which is a 256-byte structure stored immediately below the load image in memory. The PSP contains information about the current environment, including things like the command-line options that the program was started with. DOS sets both the DS and ES registers to point to the PSP’s segment address before it relinquishes control to the program.

The EXE header specifies the initial values of the SS and SP registers, which are set up to point at a high area of the uninitialized memory. LZEXE arranges SS in such a way that it could utilize well over 27 KiB of stack space if it wanted, although at its peak it only ever uses six bytes.

The initial values of the CS and IP registers are also specified in the EXE header, and point at the decompression code that will run first.

LZEXE files report zero entries in their relocation table, so DOS does not perform any relocation fixups aside from adjusting CS and SS to the correct position. A signature containing the ASCII string LZ91 appears where the relocation table would otherwise be.

The LZEXE Header

There are 14 bytes at the beginning of CS which IP is set to skip over. This is the LZEXE header. The values here dictate the decompressor’s behavior and specify how to pass control to the program once it’s fully decompressed.

| Offset (Bytes) | Size | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0h | dword | “Real” CS:IP value, relative to the decompressed program’s start address. Comprised of two words, with IP at offset 0h and CS at offset 2h. |

| 4h | dword | “Real” SS:SP value, relative to the decompressed program’s start address. Comprised of two words, with SP at offset 4h and SS at offset 6h. |

| 8h | word | Compressed program size, in 16-byte paragraphs. |

| Ah | word | Additional program size required for decompression, in 16-byte paragraphs. |

| Ch | word | Combined size of the LZEXE header, decompression code, and compressed relocation table, in bytes. |

Making Room

An LZEXE-compressed program’s first task is to move itself. This is necessary because, if the compressed payload were decompressed in the same location where DOS originally loaded it, the decompressor would begin writing decompressed program data faster than it was reading compressed data and destroy its own source material.

The code begins with a bit of housekeeping: DOS provides the PSP segment address in the ES register (as well as in DS), but the decompressor needs to use these registers for other purposes. The value in ES is pushed onto the stack for later use.

The decompressor sets up a loop that iterates once per byte in its own code segment (using the size specified in header word Ch). This loop reads the original decompressor, from high memory to low memory, and writes an identical copy at a much higher memory address. The higher address is computed by adding the distance in header value Ah to the original code’s segment address. (In the first episode, this distance is E0Fh paragraphs, or 57,584 bytes.)

Once the copy is complete, the code performs a strange jump via abuse of push and retf to resume execution in the new copy. After that point, the original copy is abandoned, ready to be overwritten by future steps.

; Stash the Program Segment Prefix (PSP) segment address for later.

push es

; - Code Segment (CS): The segment address of the code that is currently

; executing.

; - Data Segment (DS): The segment address of the source data for string-

; based instructions.

; DS is set equal to CS, since the intention is to make a copy of the

; currently-executing decompressor.

push cs

pop ds ; DS = CS

; - Count register (CX): The number of loop iterations that must occur

; when the next looping instruction is encountered.

; CX is set to the size of the entire decompressor (LZEXE header, code,

; and compressed relocation table combined) in bytes.

mov cx,word [0Ch] ; CX = header[Ch] (size of decompressor, bytes)

; - Source Index (SI): The offset into the source data. This uses DS as

; its base segment.

; - Destination Index (DI): The offset into the destination data. This

; uses ES as its base segment.

; There is an off-by-one correction done here. Although CX counts from

; (e.g.) 10..1 in the loop, SI/DI must count from 9..0 since memory

; addresses are zero-indexed.

mov si,cx

dec si ; SI = CX - 1

mov di,si ; DI = SI

; - Base register (BX): Conventionally holds the base address used in

; memory offset calculations, but can be any general value as well.

; - Extra Segment (ES): The segment address of the destination data for

; string-based instructions.

; Both BX and ES are set to a segment address some distance above DS in

; memory, with that distance specified in the "additional program size"

; header value.

mov bx,ds

add bx,word [0Ah] ; BX = DS + header[Ah] (additional size, paragraphs)

mov es,bx ; ES = BX

; Set the processor's Direction Flag (DF). Until otherwise specified, any

; instructions that automatically modify SI or DI (often called the

; "string" or string-based instructions) will do so by decrementing them.

std

; Do the following in a loop:

; 1. Set byte at ES:DI = byte at DS:SI

; 2. Decrement SI, DI, and CX by 1

; 3. When CX is 0, break

; After the loop is done, ES contains a complete copy of the data pointed

; to by DS. Note that the copy is done from high memory address to low --

; this is to prevent self-overwriting if the source and destination

; overlap at any point.

rep movsb

; BX still equals ES, the segment address of our new copy of the

; decompressor. The "magic" number 2Bh is the offset (relative to that

; segment) of the instruction immediately beyond the next `retf`

; instruction. Push this segment:offset pair onto the stack.

push bx

mov ax,2Bh

push ax

; Normally `retf` is used to return from a `call`. In this case we have

; set up something that smells like a call via the two previous pushes,

; but it's not. This has the effect of jumping into the new copy of the

; code and resuming right where we left off.

retf ; Inter-segment `ret` having segment in addition to offset

In all LZEXE-compressed files I have access to, the new copy of the decompression code ends immediately before the start of the stack segment. Because the compressed relocation table may have an odd size that does not fill an entire paragraph of memory, it’s possible for there to be 0–15 bytes of slack space between the end of the copied code and the start of the stack segment.

The job’s not quite done yet. Although the decompressor has moved, and execution has jumped into the new copy, the compressed program data has to move too.

As with the previous process, the data is copied from the location where DOS loaded it into the highest possible free spot in the load image’s allocated memory, from high to low. Unlike the previous process, however, the program data is considerably larger and the operation is broken up into a series of 64 KiB chunks.

; There is some state carried over from the previous section:

; - DS has the segment address of the *original* copy of the

; decompressor -- the one we abandoned. As a consequence of the memory

; layout, this means it is also pointing to the first paragraph past

; the *end* of the compressed program data.

; - BX has the segment address of the active decompressor. It is also

; pointing to the first paragraph past the end of a span of

; uninitialized memory.

; - DF is still set, so string operations run from high to low.

; *** This position is offset 2Bh in the code segment. ***

; - Base Pointer (BP): Conventionally holds the base offset of a stack

; frame, however this decompressor doesn't implement any. Instead, used

; as a typical general-purpose register.

; In the subsequent code, BP represents the number of paragraphs of the

; compressed program that still need to be copied. It decrements toward

; zero as the copy runs.

mov bp,word [cs:8h] ; BP = header[8h] (compressed program size, pgphs)

; - Data register (DX): General-purpose register, typically used for

; additional data. Sometimes serves as an extension of AX.

; DX will be used later as a "helper" to manipulate DS. Helpers like

; these are necessary because the segment registers cannot be used

; directly in most instruction encodings...

; ILLEGAL:

; sub ds,1

; Okay:

; mov dx,ds

; sub dx,1

; mov ds,dx

; (As an aside, BX is the helper for ES and is already initialized.)

mov dx,ds ; DX = DS

; Here, DX is pointing to the segment address where the original

; decompressor was located, which is the tail end of the compressed

; program data. BX is pointing to the segment address where the current

; decompressor is located, which is the tail end of where the new copy of

; the compressed program data should go. Both DX and BX will march toward

; zero in the following outer loop, with DS and ES (respectively)

; following along.

do_next_chunk:

; - Accumulator register (AX): Conventionally holds a running value as

; arithmetic operations are performed on it. Also holds data coming

; from/going to "load"/"store" instructions. Can be used for general-

; purpose values as well.

; AX holds the size (in paragraphs) of the current chunk being operated

; on. Usually 1000h (4,096 paragraphs or 64 KiB). When operating on the

; final (or only) chunk, AX may have a smaller remainder left.

mov ax,bp

cmp ax,1000h

jna not_big

mov ax,1000h ; AX = (BP > 1000h) ? 1000h : BP

not_big:

; Decrement BP, DS, and ES (via DX and BX) by one chunk-size. After these

; instructions, DS/ES are pointing to the bottom of a chunk source/

; destination (respectively) and BP contains the number of paragraphs

; that will need to be copied after this chunk is done.

sub bp,ax ; BP -= AX

sub dx,ax ; DX -= AX

sub bx,ax ; BX -= AX

mov ds,dx ; DS = DX

mov es,bx ; ES = BX

; AX (current chunk size) is in paragraphs; convert it into words. Set CX

; equal to AX. The next loop will iterate CX times and copy that many

; words.

mov cl,3

shl ax,cl ; AX *= 8

mov cx,ax ; CX = AX

; AX (current chunk size) is in words; adjust for off-by-one and convert

; it into bytes. Both SI and DI get the result. This sets up the initial

; state of the loop -- DS:SI holds the *byte* address of the last *word*

; in the current compressed program chunk, and ES:DI holds the same for

; the target area where that chunk is to be copied.

shl ax,1

dec ax

dec ax

mov si,ax

mov di,ax ; DI = SI = (AX - 1) * 2

; Do the following in a loop:

; 1. Set word at ES:DI = word at DS:SI

; 2. Decrement SI and DI by 2

; 3. Decrement CX by 1

; 4. When CX is 0, break

; After the loop is done, ES contains a complete copy of the compressed

; program chunk pointed to by DS. As before, this operation proceeds from

; high to low for overlap protection.

rep movsw

; If BP is 0, everything has been copied; fall through to the next

; instruction. Otherwise go back and do the next chunk.

or bp,bp

jnz do_next_chunk

; Clear DF. SI/DI will now increment during string instructions.

cld

Interestingly, the payload of each episode is small enough that the entire compressed program can be moved in a single chunk.

Flip it and reverse it.

This is a harebrained idea that I have not really tested in any way, but indulge me for a moment: If the entire payload were compressed in reverse, it should theoretically be possible to start decompressing at the high end of the compressed program data, writing to the high end of the allocated memory in descending order, without overwriting the source material or requiring a copy of the payload in the first place.

I have to think this is something that Bellard considered, and decided against for some legitimate reason. I don’t think the decompression code would have any trouble working this way, but maybe it makes the compressor too complicated or it harms the compression efficiency.

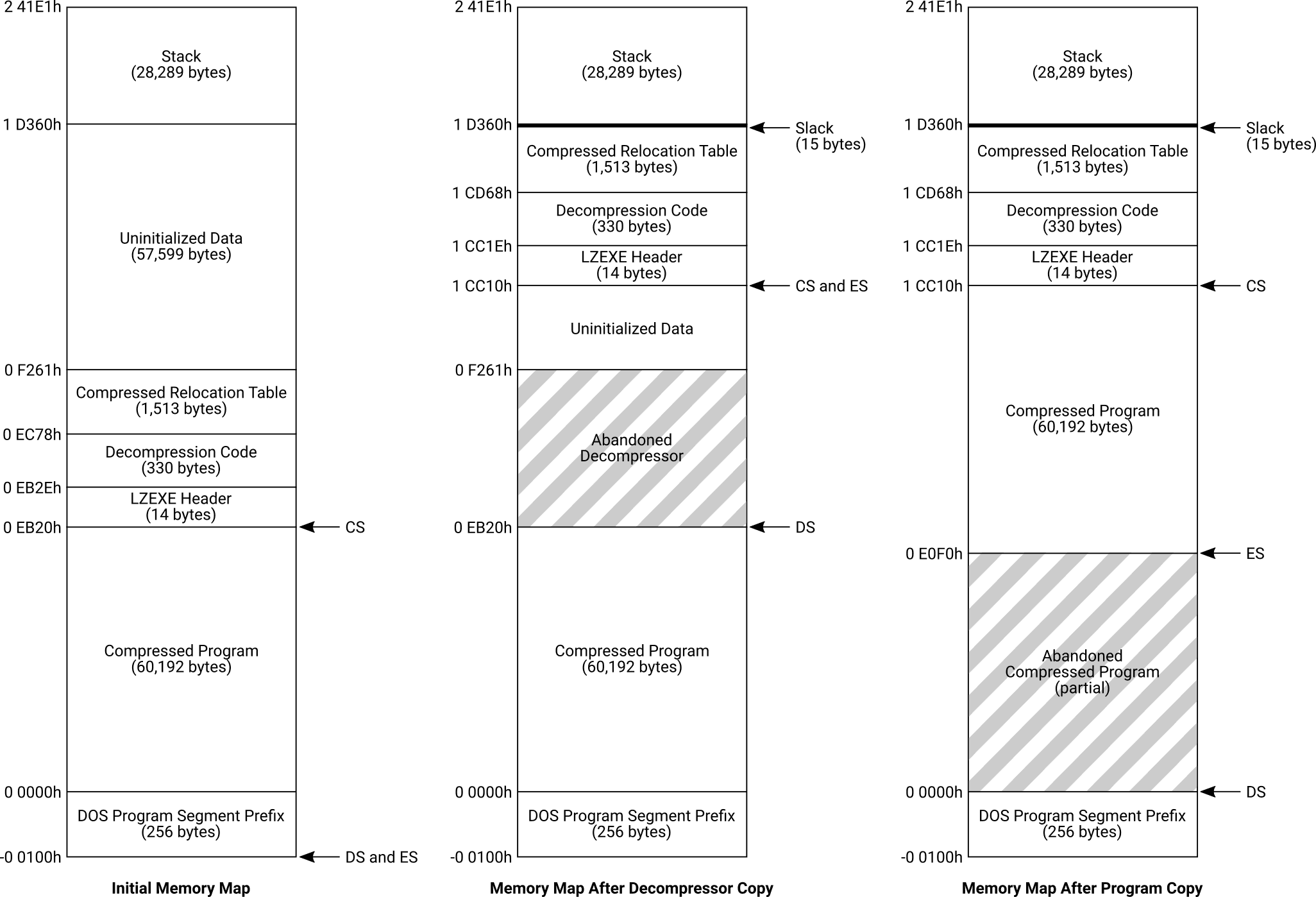

Here is a visual aid that shows the state of the memory and segment registers after each move operation:

The first map shows the memory state as soon as DOS hands control over to the decompressor code.

The second map shows the intermediate step after the decompressor is moved into its new location. Note that CS points to the new decompressor and stays there, while DS and ES point to the bottom end of the old and new decompressor, respectively.

The third map shows the memory after all move operations have been completed. In this final state, ES points to the bottom of the freshly-moved compressed program and DS points to the bottom of the destination area. The decompressor will overwrite the abandoned compressed program – and eventually the earlier portions of the copied compressed program – as it works.

Decompression

A Crash-Course in LZSS

The heart of the decompressor is the LZSS algorithm, which operates by replacing repeated occurrences of data with references to earlier instances of that same data in the decompressed output. The operation can best be described with an example from Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham that I brazenly lifted from Wikipedia:2

Original Text:

0: I am Sam

9:

10: Sam I am

19:

20: That Sam-I-am!

35: That Sam-I-am!

50: I do not like

64: that Sam-I-am!

79:

80: Do you like green eggs and ham?

112:

113: I do not like them, Sam-I-am.

143: I do not like green eggs and ham.

Compressed Text:

0: I am Sam

9:

10: (5,3) (0,4)

16:

17: That(4,4)-I-am!(19,16)I do not like

45: t(21,14)

49: Do you(58,5) green eggs and ham?

78: (49,14) them,(24,9).(112,15)(92,18).

In the compressed text, character sequences that have been previously encountered are replaced with a (position,length) pointer, while unique character sequences are preserved literally. The first pointer, (5,3), instructs the decompressor to “go to the 5th (zero-indexed) character in the text that has been decompressed so far, and copy 3 characters from that location into this one.” The pointed-to data in this case is Sam, and that is what the pointer is replaced with. The next replacement starts at character position 0 and spans a length of 4 characters, which resolves to I am. By working through the entire compressed stream and replacing all the pointers with the literal data they point to, the original text can be reconstructed perfectly.

Since replacement pointers rely on the data that has been decompressed so far, it is not possible for a pointer to refer to source data that appears after the location currently being decompressed. It is also not possible to jump around and resolve the pointers in arbitrary order – all data before a given pointer must be fully decompressed before that pointer is able to reference the correct data.

In real-world applications, it is often impractical to store the entire decompressed output and consult it during pointer resolution. More often than not, LZSS is implemented with a fixed-size sliding window that holds the most recent n characters that have been decompressed. Since the window moves during decompression, absolute positions anchored to the beginning of the data can’t work. In these scenarios, a relative distance value is used instead, which is the number of characters before the current decompression position. The key differences are:

- In the absolute model, position 0 refers to the first character in the decompressed output and incrementing this position moves the reference forward in the data.

- In the relative model, distance 0 refers to the character currently being decompressed and decrementing this distance moves the reference backward in the window. (All distance values are negative!)

LZEXE used the relative model, with a sliding window 8 KiB in size. Its core LZSS implementation was influenced by code published by Haruhiko Okumura3 in May 1988.

Run, Length, Run!

It is perfectly valid to construct a pointer that says “go to distance

-1and copy100characters from that location.” That may seem like an impossible task – how can we copy 100 characters from the position we just wrote when 99 of those characters haven’t been decompressed yet? But work through it step by step, character by character. You’ll find that it does indeed work, and the end result is 100 copies of the most recently written character.This is a form of run-length encoding, which allows for compact representation of repeated bytes or short byte patterns. The LZEXE compressor was capable of exploiting this property; roughly 0.8% of real-world LZEXE pointers have a length longer than the distance back.

A Few Pointers

The example from Green Eggs and Ham is nice, but it glosses over a few implementation details that are important to the computer. When our human eyes read the position/length numbers in the compressed text, it’s obvious where the digits of each number begin and end. We could see the number 5 or the number 7654 and immediately understand how to parse each one and what it means.

Computers have a more rigid way of looking at things. Each data type is allotted a fixed number of bits, and the allocation requirements need to be known in advance regardless of what number will actually reside in each memory location. In a scenario where we store the number 5 in (e.g.) a 12-bit field, we waste nine bits. If we try to store the number 7654 in that same 12-bit field, we can’t; it overflows the storage allocation.

Both of these situations are detrimental when talking about compression. Over-allocating space wastes bits that could be better spent elsewhere. Under-allocating space artificially constrains the distances that pointers can reach and the lengths of data that can be referenced.

No one size fits all use cases best, which is why LZEXE has three different pointer types in addition to the literal type:

| Data/Pointer Type | Bytes Used | Distance Bits | Distance Range | Length Bits | Length Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Literal uncompressed byte | 1.125 | — | — | — | — |

| Short distance | 1.5 | 8 | -1 – -256 | 2 | 2–5 |

| Long distance | 2.25 | 13 | -1 – -8,192 | 3 | 3–9 |

| Long distance/long length | 3.25 | 13 | -1 – -8,192 | 8 | 3–256 |

Note: The “Bytes Used” column contains the total amount of space required in the compressed data stream to encode a pointer of the given type. The fractional component is accounting for the space occupied by the coding scheme that differentiates these pointer types from each other, which will be discussed next.

It certainly complicates things to have three different ways to construct a pointer, but the differences in storage requirements vs. distance/length range limits are useful. The shortest encodings have the smallest usable range, but may occur more frequently in some areas. Conversely, the longest pointer can copy a significant chunk of data but only occur seldomly. These options give the compressor a varied palette to select coding schemes that perform best on each part of the data.

Symbol Coding

Take another look at the Green Eggs and Ham example and imagine something for a moment: What would happen if the antagonist in the original text was named (10,4) instead of Sam-I-am? Obviously this question is a little contrived, but it highlights an important constraint the compression scheme must abide by – it can’t impose any restrictions on what the underlying text contains, yet at the same time it must be capable of unequivocally separating literal data from pointer reference data. The decompressor needs to be able to understand when (10,4) is somebody’s name, and when (10,4) is a pointer.

Many encoding formats do this type of thing with escape characters, where such a ( would instead be written as \( to indicate that it does not have special meaning and should be taken as a literal ( character. (And, since the \ character now has significance that it didn’t have before, \\ would then be used to encode the literal \ character.) The problem with this is that it’s wasteful – it adds an entire byte to each occurrence when, in reality, all it really needs is a single true/false flag to differentiate between the two operating modes.

Fortunately, computers are full of true/false flags, and they’re called bits. Using two bytes in the compressed output, it is possible to encode 16 flag bits. This is what the LZEXE coding scheme does, interspersed with the literal data bytes.

This part gets a little abstruse.

The decompressor maintains a flag buffer containing one 16-bit word. Initially this buffer is empty. Whenever the buffer is empty and a new bit is requested, the decompressor immediately reads two bytes from the compressed data (as a little-endian word) and replenishes the buffer before returning a value. This means that the read position in the compressed data can be advanced by two bytes at any time and without any predictable pattern based on the needs of the flag buffer. This also means that the compressor needs to keep track of what will be stored in a decompressor’s flag buffer at every step of the decompression stage, and insert two flag bytes in the compressed data stream precisely when and where the decompressor will need them.

Individual flag codewords can occupy 1, 2, or 4 bits and have no intrinsic alignment. They are simply stuffed into the first place where they will fit, and could even be split across a byte boundary. The prefix bits of each codeword form a trivial Huffman coding scheme, where no codeword appears as the prefix of any other codeword.

The bit encodings are as follows:

- 1b: The corresponding data byte is not compressed. Read the byte literally into the decompressed output.

- 00xxb: Read one data byte. This byte represents a distance back, between -1 and -256 (two’s complement). The

xxbits in the flag codeword encode a length:- 00b: Length = 2.

- 01b: Length = 3.

- 10b: Length = 4.

- 11b: Length = 5.

- 01b: Read two data bytes and interpret as a little-endian word. The data word’s bit pattern is masked as

xxxx xyyy zzzz zzzzwith the following interpretation:- x xxxx zzzz zzzz: Distance back, between -1 and -8,192 (two’s complement).

- yyy:

- 001b: Length = 3.

- 010b: Length = 4.

- 011b: Length = 5.

- 100b: Length = 6.

- 101b: Length = 7.

- 110b: Length = 8.

- 111b: Length = 9.

- 000b: Special handling is required. See next paragraph.

The flag codeword 01b with compressed data matching xxxx x000 zzzz zzzz requires special handling. When this bit pattern is encountered, an additional byte is read from the compressed data and one of the following actions is taken based on its value:

- 0h: The end of the compressed data has been reached, and decompression can stop. The distance value in

x xxxx zzzz zzzzis meaningless. - 1h: A segment change is required. Normalize ES:DI and DS:SI to prevent running off the end of a segment boundary. The distance value in

x xxxx zzzz zzzzis meaningless. - 2h-FFh: This byte represents a data length between 3 and 256 (byte’s value + 1). The distance back is between -1 and -8,192 (two’s complement), from the

x xxxx zzzz zzzzbit mask that was computed above.

The important takeaway here is that the flag codewords have a variable length, and different pointer types consume different numbers of data bytes. The flag codewords and data bytes are interleaved with no real regular pattern or synchronization, and usually flag bytes are not stored adjacent to the data bytes they refer to (due to the delaying effect of the flag buffer). There are no checksums and there is no error correction. If the decompressor loses its place, or the source data is corrupt in even a minor way, the decompressed result can be profoundly wrong.

The following table summarizes the encodings and relative prevalence of each operating mode in the game files I examined for this project.

| Flag Codeword | Data Bytes Read | Interpretation of Data Byte(s) | Operating Mode | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1b | 1 | source | Copy source byte literally. | 55% |

| 00xxb | 1 | distance | Copy xx bytes from distance bytes back. | 18% |

| 01b | 2 | zzzz zzzz, xxxx xyyy | Copy yyy bytes from x xxxx zzzz zzzz bytes back. | 21% |

| 01b | 3 | zzzz zzzz, xxxx x000, 0h | End of compressed data. | Once per file. |

| 01b | 3 | zzzz zzzz, xxxx x000, 1h | Segment change. | Twice per file. |

| 01b | 3 | zzzz zzzz, xxxx x000, length | Copy length bytes from x xxxx zzzz zzzz bytes back. | 6% |

The Code

This section, which deals with the flag buffer and symbol coding along with the actual decompression, is the longest portion of the decompressor. Several pieces of the code are repeated – a call into a procedure could’ve shortened this by quite a bit at the expense of execution speed. I will try not to spend too much time documenting the repeated portions.

; A bit of a switcheroo here: DX was the helper register for *DS*, which

; was the segment address of the original compressed data during the

; previous copy operation. BX was the helper register for *ES*, which was

; the segment holding the new copy of that same data. Now the roles are

; reversed; the new copy is the source while the original data will be

; overwritten as the program decompresses. Since the data was copied from

; high to low, both registers now point to the very beginning of their

; respective data areas.

mov es,dx ; ES = DX

mov ds,bx ; DS = BX

; SI is the read offset within the compressed data (in DS).

; DI is the write offset within the decompressed data (in ES).

xor si,si ; SI = 0

xor di,di ; DI = 0

; DX (and later DL) represents the number of bits currently available in

; the flag buffer. Each bit read will decrement this, and when it

; decrements to zero the buffer must be replenished.

mov dx,16 ; DX = 16

; Read one word from DS:SI into AX, then increment SI by 2. The value

; read has 16 bits that initialize the flag buffer. Store it in BP.

lodsw

mov bp,ax ; BP = AX

next_codeword:

; === BEGIN FLAG BUFFER CODE ============================================

; This pair of instructions shifts a single bit off the right side of BP

; and decrements the counter in DX to reflect the fact that one bit has

; been removed from the buffer. Unlike in higher-level languages, the

; most recently shifted-out bit is preserved in the processor's Carry

; Flag (CF). The code below relies on this behavior.

shr bp,1 ; CF = BP & 1; BP >>= 1

dec dx ; DX--

; If DX is zero, we need to replenish the buffer in preparation for a

; future read. Fall through to do so. Otherwise, skip over it.

jnz buffer_is_okay

; Roughly the same steps as the initialization of the flag buffer from

; before. Read one word from DS:SI into AX, increment SI by 2, store the

; bits in BP, and update DL to reflect the fact that there are now 16

; bits available for reading.

lodsw

mov bp,ax ; BP = AX

mov dl,16 ; DL = 16

buffer_is_okay:

; Here, CF contains a single flag bit read from the input data, and the

; flag buffer has at least one bit ready to read for next time.

; === END FLAG BUFFER CODE ==============================================

; If CF is 0, we're looking at some kind of pointer and need to jump to

; the code that handles that. Otherwise, fall through to the simpler

; "literal byte" handler.

jnc looks_like_pointer

; ***********************************************************************

; * Handler code for flag codeword 1b: Literal byte. *

; ***********************************************************************

; When the first flag code bit is 1, that means no further flag code bits

; need to be read and the decompressor must simply copy one input byte to

; the output.

; Set byte at ES:DI = byte at DS:SI, then increment SI and DI by 1.

movsb

; Ready for more...

jmp next_codeword

looks_like_pointer:

; Here, we already read a 0 from the input data's flag bits, which means

; we need to read another bit to figure out what to do.

; CX will be used as a temporary accumulator register, so ensure there is

; o garbage stored there.

xor cx,cx ; CX = 0

; Read one flag bit into CF...

; === DUPLICATE OF FLAG BUFFER CODE =====================================

shr bp,1

dec dx

jnz buffer_is_okay_2

lodsw

mov bp,ax

mov dl,16

buffer_is_okay_2:

; === END OF FLAG BUFFER DUPLICATE ======================================

; If CF is 1, jump to the long distance handler. Otherwise fall through

; to the short distance handler.

jc long_distance_code

; ***********************************************************************

; * Handler code for flag codeword 00xxb: Short distance. *

; ***********************************************************************

; Short distance codewords have two bits which we refer to as `xx`

; encoded directly in the flag bits. These need to be read now.

; Read the first bit of `xx` into CF...

; === DUPLICATE OF FLAG BUFFER CODE =====================================

shr bp,1

dec dx

jnz buffer_is_okay_3

lodsw

mov bp,ax

mov dl,16

buffer_is_okay_3:

; === END OF FLAG BUFFER DUPLICATE ======================================

; Append the most recently read flag bit onto the right side of CX while

; shifting the existing bits to the left one position.

rcl cx,1 ; CX = (CX << 1) | CF

; Read the second bit of `xx` into CF...

; === DUPLICATE OF FLAG BUFFER CODE =====================================

shr bp,1

dec dx

jnz buffer_is_okay_4

lodsw

mov bp,ax

mov dl,16

buffer_is_okay_4:

; === END OF FLAG BUFFER DUPLICATE ======================================

; Same as the previous bit; shift CF onto the right side of CX.

rcl cx,1 ; CX = (CX << 1) | CF

; The `xx` flag bits directly encode values 0..3, but the actual `length`

; range is 2..5. After the increments, CX contains the number of bytes

; that will need to be copied to reconstruct this piece of data.

inc cx

inc cx ; CX += 2

; - High/Low register parts (_H/_L): 8-bit views into the corresponding

; 16-bit (_X) registers. _H has the high-order bits, and _L has the

; low-order bits. Modifying _H or _L directly changes the value in _X

; and vice-versa.

; Read one byte from DS:SI into AL, then increment SI by 1. Use this

; value and a constant to build BX piecewise. The bits in BH are forced

; to FFh, and the low bits in BL can be any value 0h..FFh that was read

; from the compressed data. As a two's complement value:

; FF00h == -256

; FFFFh == -1

; This final value in BX is the "distance back," a negative number of

; bytes to look back in order to locate the source data that needs to be

; copied.

lodsb

mov bh,0FFh ; BH = FFh

mov bl,al ; BL = AL

; Jump to the data-copying code.

jmp copy_bytes

long_distance_code:

; ***********************************************************************

; * Handler code for flag codeword 01b: Long distance. *

; ***********************************************************************

; Read one word from DS:SI into AX, then increment SI by 2. The value

; read contains a packed distance and length. Mask AX using the pattern

; `xxxx xyyy zzzz zzzz` into `111x xxxx zzzz zzzz`. As a two's complement

; value:

; E000h == -8,192

; FFFFh == -1

; This final value in BX is the "distance back," a negative number of

; bytes to look back in order to locate the source data that needs to be

; copied.

lodsw

mov bx,ax ; BL = AL

mov cl,3

shr bh,cl

or bh,0E0h ; BH = (AH >> 3) | 11100000b

; Mask AH (having the pattern `xxxx xyyy`) into `0000 0yyy`. AH now

; contains either a length or a special handling code.

and ah,7h ; AH &= 00000111b

; If the code in AL is 0, jump to the special handlers. Otherwise fall

; through to set up a data copy.

jz needs_special_handling

; The high bits of CX are all zero already. AH has the `yyy` bits, which

; directly encode values 1..7 (cannot be 0 here), but the actual `length`

; range is 3..9. After incrementing, CX contains the number of bytes that

; will need to be copied to reconstruct this piece of data.

mov cl,ah

inc cx

inc cx ; CX = AH + 2

; Fall through to the data-copying code.

copy_bytes:

; ***********************************************************************

; * Data-copying code. *

; ***********************************************************************

; Here, ES:DI points to the position where decompressed data is currently

; being written. BX is a (negative) distance relative to the write

; position from which data should be read, and CX is the number of bytes

; that still need to be copied.

; Copy one byte from ES:(DI + BX) to ES:DI, then increment DI. This is

; reading a byte from some previous location in the *destination*

; segment, and writing it to the current position in the destination.

mov al,byte [es:bx+di] ; AL = byte value at ES:(DI + BX)

stosb ; byte value at ES:DI = AL; DI++

; CX--. If CX > 0, jump back to copy_bytes. Otherwise, fall through.

loop copy_bytes

; Ready for more...

jmp next_codeword

needs_special_handling:

; ***********************************************************************

; * Handler code for various special circumstances. *

; ***********************************************************************

; Read one byte from DS:SI into AL, then increment SI by 1. This value

; either specifies a special action to take, or it is the length for a

; long-length copy operation.

lodsb

; If AL is 0, decompression is over and it's time to jump to the section

; of the code that does relocations. Otherwise, fall through.

or al,al

jz start_relocations ; This is in a separate code block further down.

; If AL is 1, jump to segment change code. Otherwise, fall through.

cmp al,1

jz change_segment

; ***********************************************************************

; * Handler code for long distance with long length. *

; ***********************************************************************

; The high bits of CX are all zero already. AL can directly encode values

; 2..255 (cannot be 0 or 1 here), but the actual `length` range is

; 3..256. After incrementing, CX contains the number of bytes that will

; need to be copied to reconstruct this piece of data.

mov cl,al

inc cx ; CX = AL + 1

; Jump to the data-copying code. BX has an appropriate value that was set

; in the long-distance handling code above.

jmp copy_bytes

change_segment:

; ***********************************************************************

; * Handler code for a segment change. *

; ***********************************************************************

; Segments (like DS and ES) and offsets (like SI and DI) are combined

; together to make physical addresses. The conversion is:

; address = (segment << 4) + offset

; There are multiple segment:offset combinations that will result in the

; same result address. A segment:offset pair is said to be "normalized"

; if the offset's high 12 bits are all zero -- in other words, if the

; offset is in the range 0..Fh. Normalization is desirable so that the

; offset doesn't grow so large that it "wraps around" back to zero (which

; would cause a reference to an earlier part of memory than was

; intended).

; This code performs that normalization, while preserving the sliding

; window. The compressor can call for this whenever it wants. In

; practice, it seems to occur roughly once every A000h output bytes.

; First, normalize ES:DI. In the process, add 2000h to DI and subtract

; 200h from ES. This has the net effect of still pointing to the same

; data, but with 8 KiB of room at the beginning of the segment so the

; entire sliding window can remain accessible by pointers. (AX is used as

; a temporary register here.)

mov bx,di ; BX = DI

and di,0Fh

add di,2000h ; DI = (DI & 00001111b) + 2000h

mov cl,4

shr bx,cl

mov ax,es

add ax,bx

sub ax,200h

mov es,ax ; ES = (ES + (BX >> 4)) - 200h

; Normalize DS:SI. As there is no random-access needed here, the

; translation has no further adjustments.

mov bx,si ; BX = SI

and si,0Fh ; SI = SI & 00001111b

shr bx,cl

mov ax,ds

add ax,bx

mov ds,ax ; DS = DS + (BX >> 4)

; Ready for more...

jmp next_codeword

I’m going to guess that the LZEXE compressor that created these payloads has some downright heinous stuff inside to make it all work.

Tricks and Traps

Next is the following:

; ???

sub al,byte [bp+41h]

inc dx

sub cl,byte [0BE1Fh]

pop ax

add word [bp+di-7Dh],bx

ret

adc byte [bx+di+31DAh],cl

jmp far [si-3FF8h]

What the heck is going on here? There are strange displacements, a ret and a far jmp that don’t make any sense, and this whole area seems more than a little broken.

What happened is this: The decompressor contains the bytes 2Ah 46h 41h 42h 2Ah immediately after the end of the main decompression loop, but these bytes are never executed by any path through the code. This is data – an ASCII message consisting of *FAB*, a nice little calling card left by Bellard.

These bytes encode a valid (if nonsensical) series of x86 instructions which also desynchronize many disassemblers for a number of subsequent instructions. In order to correctly disassemble the file, the disassembler must be intelligent enough to realize that this is data, not code (or a human will have to hex-edit the offending bytes to nop or something similar).

Relocation

In a normal DOS executable file, the relocation table is part of the EXE header. Each relocation table entry is a 4-byte segment:offset pointer into the load image, and each pointed-to memory location is “fixed up” by adding the base load offset to the value in memory. DOS takes care of all of this as it loads the program.

Unfortunately, it also takes up quite a bit of space. The average game in the series has over 1,300 relocation table entries, which would occupy well over 5 KiB of space using the DOS scheme. LZEXE-compressed executables improve this situation by specifying zero relocation entries in the EXE header, and performing the fixups directly based on a more compact map of which memory locations need to be changed. In practice, an LZEXE-compressed relocation table can be one-quarter the size of the equivalent DOS relocation table.

The key insight is that relocation fixups occur with fairly high density. Rather than specifying each fixup with a 4-byte segment:offset pointer, LZEXE only encodes the distance from the previous fixup. This results in a far more efficient pack, with most relocations requiring only one byte to express.

The distance codewords have a variable length. Distances from 1 to 255 are encoded with that literal number as a single byte. Distances of 256 or greater require three bytes: a 0 byte to signal that this is a long codeword, followed by two bytes, interpreted as a little-endian number, which encodes a distance that can be as large as 65,535.

There are also two special encodings that represent something other than distance:

- 00h, 0000h: Represents a segment change. If this byte pattern is encountered, the relocation segment address is incremented by FFFh, which has the effect of kicking the relocation loop 65,520 bytes forward in the decompressed program. This never occurs in any of the LZEXE-compressed files I have access to, but presumably allows a way to skip – perhaps repeatedly – over large spans where no relocations occur.

- 00h, 0001h: Represents the end of the relocation table. Once this byte pattern is encountered, relocation stops.

The special encodings don’t detract from the expressiveness of the scheme – a zero-byte distance is nonsensical, and a one-byte distance – in addition to also being nonsensical – could be handled by the single-byte encoding.

start_relocations:

; The compressed relocation table resides in CS. Set DS so this can be

; used as the source segment.

push cs

pop ds ; DS = CS

; The magic number 158h is the size of the LZEXE header + the size of the

; decompressor code in bytes. This sets DS:SI up to point to the first

; entry in the compressed relocation table.

mov si,158h ; SI = 158h

; The PSP segment address was stashed on the stack way back at the

; beginning of the decompression code. The PSP address was chosen by DOS

; when it originally loaded the EXE file, and it could reside almost

; anywhere in memory, but it's guaranteed to be 256 bytes in size. 10h

; paragraphs (256 bytes) above the PSP is the first paragraph of the

; decompressed program.

pop bx

add bx,10h ; BX = <stashed PSP segment address> + 10h

; BX now contains the starting segment address of the decompressed

; program relative to memory address zero. This means that the value in

; BX must be added to the value at each relocatable memory location to

; properly "fix up" the program for its loaded position.

; DX is the helper register to manipulate ES. It is set equal to BX, the

; decompressed program's starting segment address.

mov dx,bx ; DX = BX

; DI is the offset (relative to ES) of the most recent relocation that

; has been performed. We have not relocated anything yet, so it is

; artificially set to the 0th byte of the program. This initialization

; has the side-effect that it's not possible to apply a relocation to the

; very first bytes of a program. I can't easily think of a scenario where

; this would be a practical issue.

xor di,di ; DI = 0

read_next_entry:

; Read one byte from DS:SI into AL, then increment SI by 1. The value

; read could be either a distance or flag for a multi-byte encoding.

lodsb

; If AL is 0, jump to the handler code for multi-byte entries. Otherwise,

; fall through to the next instruction.

or al,al

jz need_next_word

; ***********************************************************************

; * Handler for single-byte fixup codeword. *

; ***********************************************************************

; AL contains a distance from 01..FFh (cannot be 0 here), but AH might

; have garbage in it. Zero this out so we can use AX and see the same

; value AL holds.

mov ah,0 ; AH = 0

apply_fixup:

; DI is the most recently fixed-up offset, and AX is the distance that

; was just read from the compressed relocation table. Increment DI by

; this distance.

add di,ax ; DI += AX

; This re-normalizes the segment:offset pair by adding the high 12 bits

; of DI onto ES, and then masking DI so only the low 4 bits remain. AX is

; a temporary register and, as before, DX is only a helper for changing

; ES.

mov ax,di ; AX = DI

and di,0Fh ; DI &= 00001111b

mov cl,4

shr ax,cl

add dx,ax ; DX += AX >> 4

mov es,dx ; ES = DX

; Actually perform the fixup. ES:DI is the memory location we've lined

; up, and BX is the segment address to be added to the value here.

add word [es:di],bx ; <word ES:DI points to> += BX

; Move along to the next table entry...

jmp read_next_entry

need_next_word:

; Read one word from DS:SI into AX, then increment SI by 2. The value

; read could be either a distance or a special signal.

lodsw

; If AX is 0, fall through to the segment change code. Otherwise jump to

; the next test in the series.

or ax,ax

jnz not_segment_change

; ***********************************************************************

; * Handler code for 00h 0000h: Segment change. *

; ***********************************************************************

; Adjust ES up by FFFh paragraphs (65,520 bytes) without changing DI.

; This is an exceedingly rare event that I've never actually seen.

add dx,0FFFh ; DX += FFFh

mov es,dx ; ES = DX

; Move along to the next table entry...

jmp read_next_entry

not_segment_change:

; If AX is 1, fall through to the next section (this is the indicator

; that relocations are finished). In all other cases, the value within AX

; is treated as a distance and we can jump directly into the fixup code

; with it.

cmp ax,1

jnz apply_fixup

; ***********************************************************************

; * Handler code for 00h 0001h: End of relocation table. *

; ***********************************************************************

; Continues below...

Passing the Torch

At this point, the memory contains the same thing it would’ve contained had the executable never been LZEXE-compressed in the first place. A few things need to be changed in the processor’s registers for the decompressed program to start, however.

To make it seem as if LZEXE had never been present:

- DS and ES must point to the PSP segment address.

- SS and SP must point to a reasonable location.

- CS and IP must point to the first instruction of the program code.

In particular, changing SS:SP is a delicate operation because of the ever-present chance of an interrupt occurring at exactly the wrong time and accessing a half-configured stack. It’s also not possible to directly change CS:IP; that must occur with an inter-segment jmp instruction.

; BX still points to the base segment address of the decompressed

; program. That address is copied to a work area in AX.

mov ax,bx ; AX = BX

; Set SI/DI to the "real" SS/SP values from the LZEXE header,

; respectively. Add AX to the SS value in SI to relocate it correctly.

; SI/DI are temporary helpers -- the actual switchover happens later.

mov di,word [4h] ; DI = header[4h] (real SP value)

mov si,word [6h]

add si,ax ; SI = header[6h] + AX (real SS value)

; Relocate the "real" CS register value by modifying the the LZEXE header

; data directly.

add word [2h],ax ; header[2h] += AX (real CS value)

; Here, AX is pointing to the segment address of the start of the

; decompressed program. Subtract 10h paragraphs (256 bytes) from it to

; get the segment address of the PSP. Put this value in DS and ES to

; restore both registers to the state they would've been in if DOS had

; loaded the program directly.

sub ax,10h ; AX -= 10h

mov ds,ax ; DS = AX

mov es,ax ; ES = AX

; BX is going to be used to refer to header[0h] in the final far `jmp`.

xor bx,bx ; BX = 0

; - Stack Segment (SS): The segment address of the stack area.

; - Stack Pointer (SP): The offset into the stack area. This value

; decrements as values are `push`ed and increments as values are

; `pop`ped.

; Switch the stack registers to the location the decompressed program

; expects. These are fenced with "clear interrupt flag" and "set

; interrupt flag" instructions to temporarily prevent interrupts from

; being handled. Otherwise, if the system were unlucky enough to

; experience an interrupt after SS was set but before SP was set, the

; interrupt's implicit pushes and pops would trash something in an

; unpredictable location in memory.

cli

mov ss,si ; SS = SI

mov sp,di ; SP = DI

sti

; CS is the decompressor's segment address, which starts with the LZEXE

; header. BX is 0, so CS:BX is header[0h]: the "real" CS:IP header value.

; This starts the decompressed program, and control never needs to return

; here.

jmp far [cs:bx]

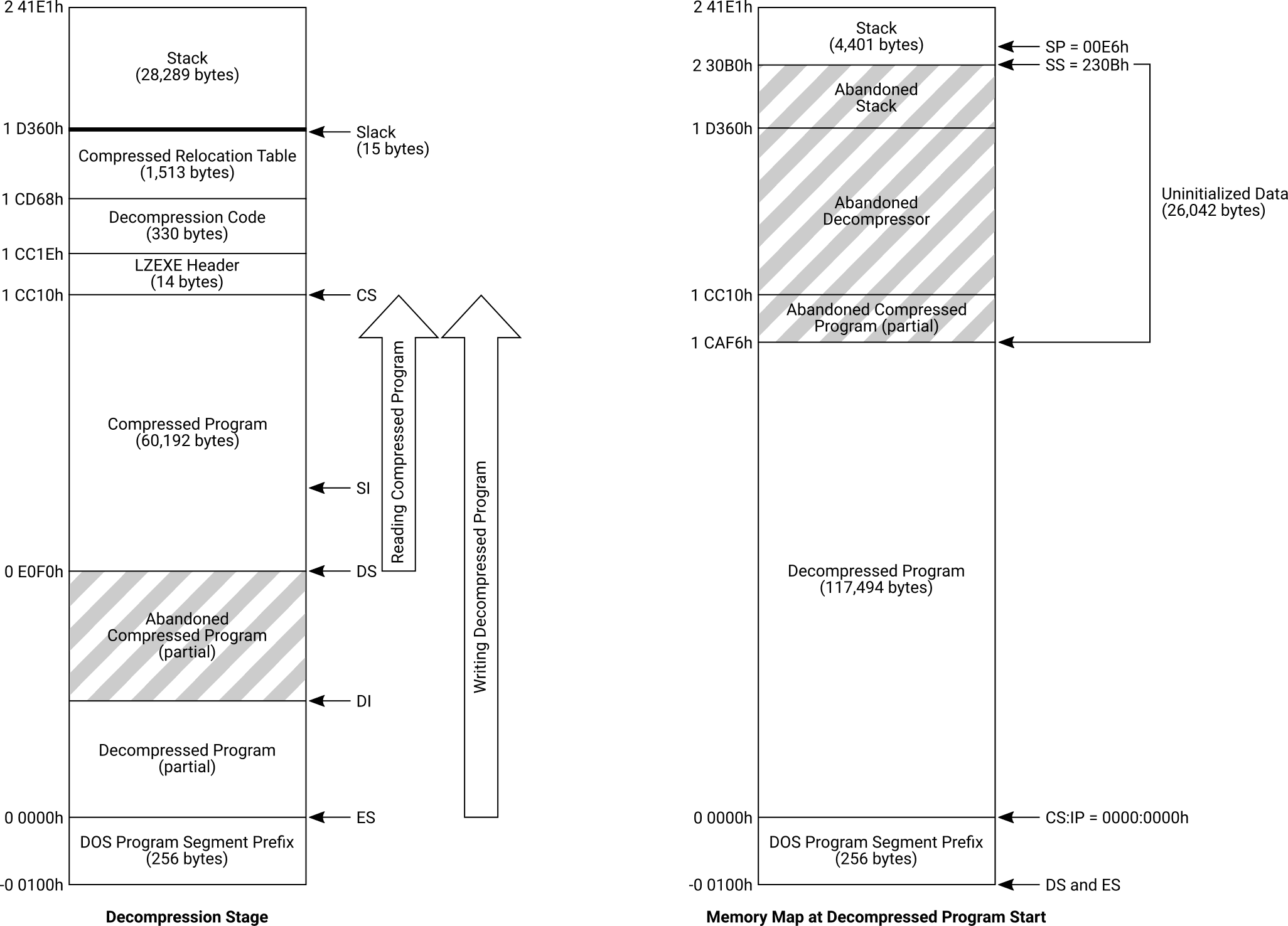

Here’s a visualization of the memory during decompression, and then at the moment the decompressed program begins executing on its own:

The memory allocated to the stack segment now has a more reasonable size of about 4 KiB.

Interestingly, the decompressed program’s “uninitialized” data area is filled with abandoned data: the old stack, the entire decompressor, and the topmost couple of compressed program paragraphs. LZEXE did not zero out this area before launching the program. Apparently DOS never did that either,4 even when loading programs normally. Programs had to operate on the assumption that the “uninitialized” area really was uninitialized, and could hold any random garbage.

Some languages, notably C, guarantee that uninitialized data is actually set to a zero/null value by default. Since DOS didn’t do this, the runtime had to do it itself. This was another one of Borland C0.ASM’s startup responsibilities.

And that’s how it all worked. All of this – everything in this section – happened in that split-second between when a user pressed the Enter key at the DOS prompt and when the screen cleared. It was quick, transparent, and it all just worked. LZEXE was a stalwart tool of DOS game publishers, and this decompression scheme is forever enshrined in dozens if not hundreds of games that people are still playing today.