User Interface Functions

In the field of DOS game programming, there is really no such thing as a “user interface library” to ease development. The programmer is ultimately responsible for everything: drawing menus and windows on the screen, drawing text character-by-character, and handling input from the keyboard. This game is no exception, and it contains a handful of functions that are responsible for presenting the basic menu interface.

Design Philosophy

The game has no concept of a “window” per se. While text generally appears inside graphical boxes called frames, there is no link between an individual frame and the text contained inside it. There is also no buffer for screen contents that are obscured by the frontmost frame – once a new frame box is drawn, anything behind it is irrevocably destroyed and would need to be redrawn if it needed to be made visible again.

Each text frame conventionally contains a wait spinner to indicate to the user that keyboard input is required to proceed. In cases where text entry is expected, the wait spinner also serves as a text insertion cursor which moves in tandem with the text being entered.

The UI drawing functions use low-level drawing routines internally, which all honor the current state of the draw/active pages. Typically the menu system explicitly uses page 0, eschewing the page-flipping mechanism in favor of a simpler “direct” drawing pattern. As each drawing routine is called, its effect becomes immediately visible on the screen.

DrawTextFrame()

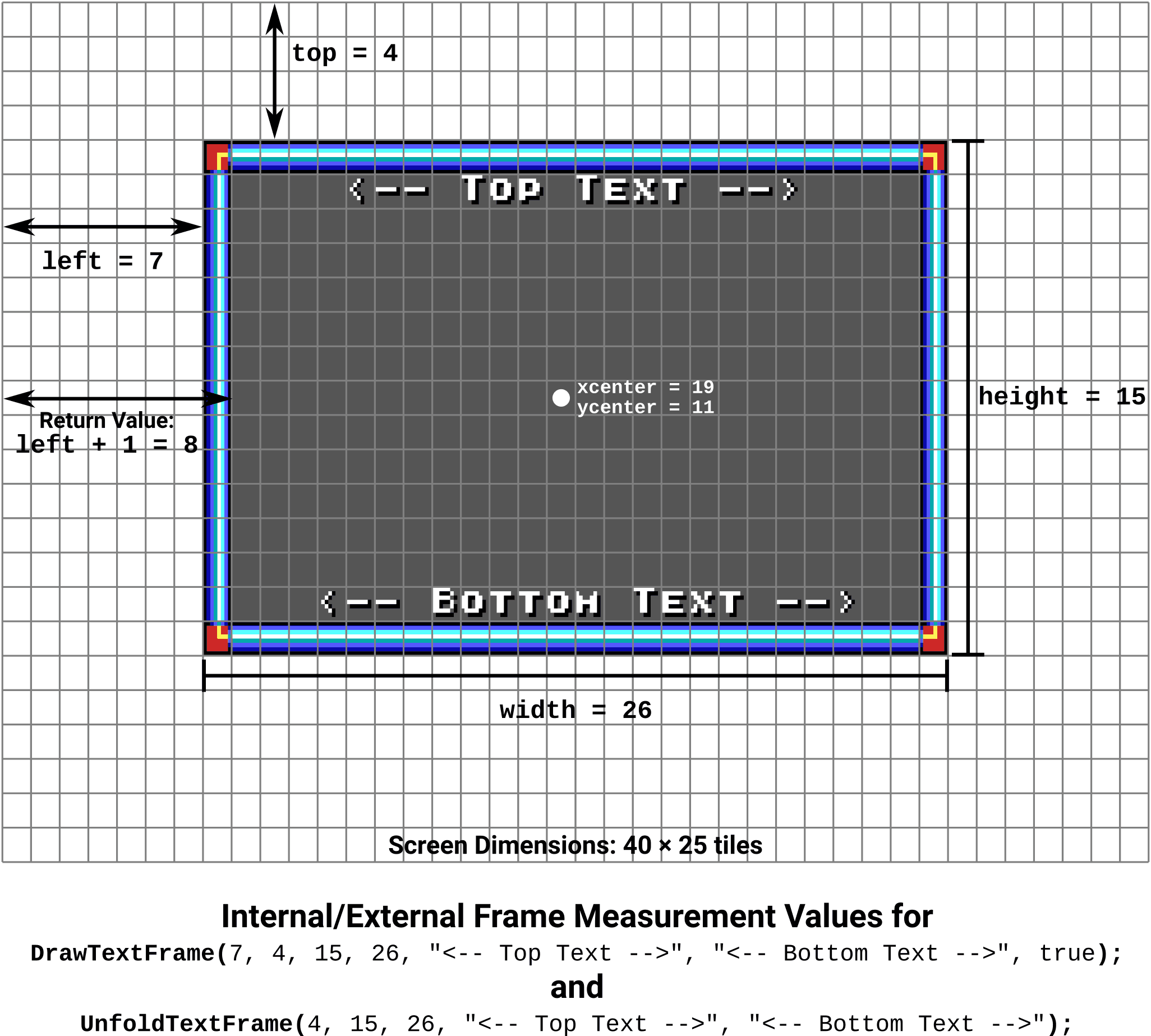

The DrawTextFrame() function draws an empty text frame to the current draw page with the upper-left corner at tile position (left, top) and a total size of width × height tiles. The top and bottom edges of the frame are prefilled with top_text and bottom_text respectively, aligned according to the centered flag. The top/bottom texts are rendered with DrawTextLine(), and support all animation/image drawing commands supported by that function.

The return value is left + 1, which is conceptually the X tile coordinate of the left edge of the inner text area. (The usefulness of this return value is more apparent when paired with UnfoldTextFrame(), which does not take a left argument.)

The frame is displayed as a blue/gold border, one tile thick, that surrounds a background of solid gray. The act of drawing the border and background erases any screen content that was previously present. Visually, the frame is measured as follows:

Note: The inner

xcenterandycentervariables come into play when frames are drawn throughUnfoldTextFrame(). They are shown here to give a grand overview of all measurement points in a frame.

Frames are always drawn horizontally centered in the game, but this is not technically required here. Non-centered frames were apparently not tested thoroughly, and may display strangely under certain scenarios.

word DrawTextFrame(

word left, word top, int height, int width, char *top_text,

char *bottom_text, bbool centered

) {

register int x, y;

EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE();

Throughout this function, the x and y variables hold the screen coordinates of the tile position currently being operated on. These are declared as register to suggest that the compiler keep these in processor registers instead of stack memory.

The frame is built entirely of solid tile graphics, which are stored in the EGA’s onboard memory. For the drawing functions to properly copy this data from one location in video memory to another, the EGA hardware must be in placed in latched write mode with the EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE() macro.

for (y = 1; y < height - 1; y++) {

for (x = 1; x < width - 1; x++) {

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(TILE_DARK_GRAY, x + left, y + top);

}

}

This pair of loops iterates horizontally and vertically through the area covered by the frame’s gray background, skipping the border area (hence starting at 1 and ending at - 1 relative to the frame’s width and height).

At each x and y combination, DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY() draws a tile of solid dark gray (TILE_DARK_GRAY) to the draw page. This simultaneously erases any existing screen content at that position, and creates a blank canvas upon which new content can be legibly drawn.

for (y = 0; y < height; y++) {

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(TILE_TXTFRAME_WEST, left, y + top);

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(TILE_TXTFRAME_EAST, left + width - 1, y + top);

}

Here the left and right borders (TILE_TXTFRAME_WEST and TILE_TXTFRAME_EAST, respectively) are drawn in tandem. Drawing proceeds from top to bottom, including tile positions that are going to be subsequently redrawn by the corner tiles.

for (x = 0; x < width; x++) {

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(TILE_TXTFRAME_NORTH, x + left, top);

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(TILE_TXTFRAME_SOUTH, x + left, top + height - 1);

}

Similarly, TILE_TXTFRAME_NORTH and TILE_TXTFRAME_SOUTH are drawn in left-to-right fashion to produce the top and bottom borders. These calls redraw the corner tile positions again with content that will not be visible in the end.

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(TILE_TXTFRAME_NORTHWEST, left, top);

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(TILE_TXTFRAME_NORTHEAST, width + left - 1, top);

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(TILE_TXTFRAME_SOUTHWEST, left, top + height - 1);

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(

TILE_TXTFRAME_SOUTHEAST, width + left - 1, top + height - 1

);

Four distinct calls to DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY() produce the expected corner tiles:

TILE_TXTFRAME_NORTHWESTfor the upper-left cornerTILE_TXTFRAME_NORTHEASTfor the upper-right cornerTILE_TXTFRAME_SOUTHWESTfor the lower-left cornerTILE_TXTFRAME_SOUTHEASTfor the lower-right corner

If the “something - 1” bits seem confusing, you’re not alone. This is the sort of thing that has flummoxed every computer programmer at some point, leading to a condition known as off-by-one or “fencepost” errors.1 The most succinct way to catch and reason about this sort of thing is, are you counting your fingers, or the spaces between your fingers? The situation certainly isn’t helped by the fact that the screen’s coordinate system starts at zero.

With that, the basic structure of the frame has been drawn.

if (centered) {

DrawTextLine(20 - (strlen(top_text) / 2), top + 1, top_text);

DrawTextLine(

20 - (strlen(bottom_text) / 2), top + height - 2, bottom_text

);

} else {

DrawTextLine(left + 1, top + 1, top_text);

DrawTextLine(left + 1, top + height - 2, bottom_text);

}

Most frames contain a line of text at their top and/or bottom inside edges. This is drawn here. If a caller wishes to draw a frame without text in one of these positions, passing an empty string in top_text or bottom_text will accomplish that.

There are two possible modes that can be chosen: centered or not. For all practical purposes, centered is always true in the retail game, resulting in horizontally-centered text within the frame. The X position is computed by taking half of the screen width in tiles, and subtracting half of the string length of top_text as reported by strlen(). The Y position for the top text is the frame’s top, plus one to clear the top border row. The position for bottom_text is computed similarly, using top + height to determine the bottom position of the frame and subtracting two to clear the bottom border row and to correct for an off-by-one error. Each line of text is passed to DrawTextLine(), which draws the text characters from the font tile data.

Note:

Centered drawing always centers the text horizontally relative to the screen, and does not account for combinations of the frame’s

leftorwidthvalues. This means that, if the frame is not positioned in the center of the screen, the centered text will not appear in the center of that frame.This does not cause issues in the game, because almost all frames are drawn through

UnfoldTextFrame()which always centers the frame horizontally.

If centered was false, a simpler pair of DrawTextLine() calls places top_text and bottom_text at the leftmost edge of the frame’s interior. This does account for the frame’s left position, and renders correctly anywhere on the screen. The calculation for the Y positions is identical to the centered variant.

return left + 1;

}

With the frame and its top/bottom text fully drawn, the function returns. The return value is the left position of the frame on the screen, plus one to clear the left-hand border. Any subsequent calls to another drawing function can use this return value to choose an appropriate X value that falls inside the frame’s border.

UnfoldTextFrame()

The UnfoldTextFrame() function draws an animated, empty text frame to the current draw page with the top edge at tile position top and a total size of width × height tiles. The top and bottom edges of the frame are prefilled with top_text and bottom_text respectively. The top/bottom texts are rendered with DrawTextLine(), and support all animation/image drawing commands supported by that function. The frame and its top/bottom texts are always centered horizontally on the screen. The return value is the X tile coordinate of the left edge of the inner text area.

The animated “unfolding” effect is achieved with multiple successive calls to DrawTextFrame() with a small wait in between each call. A tiny frame starts in the center of the drawing area, which expands horizontally until it reaches the desired width. Once that happens, the frame begins to expand vertically until it reaches the final height, at which point the top and bottom texts are added. This function blocks until the final size has been reached, and larger frames require more iterations (and more time) to do this than smaller frames do.

word UnfoldTextFrame(

int top, int height, int width, char *top_text, char *bottom_text

) {

int left = 20 - (width >> 1);

word xcenter = 19;

word ycenter = top + (height >> 1);

word size;

int i;

This function always centers the frame horizontally, and these are the calculations that support this. The left position is computed by taking half of the screen width in tiles and subtracting half of the passed width. In this function, values are halved by shifting the values to the right one bit position instead of dividing by 2; both approaches would return the same result in practice.

The xcenter and ycenter values are (roughly) the center of the drawing area. This sets up the initial state of the animation, where the frame is drawn as a tiny 3×2 cluster of border tiles:

xcenteris set to half of the screen width in tiles, minus one – this gives the frame a small bit of initial width so it is large enough to display in a meaningful way.ycenteris initialized to the top position of the desired end state of the frame, plus half of the final frame’s height (again, using a bit shift instead of division). This centers the drawing vertically.

size = 1;

for (i = xcenter; i > left; i--) {

DrawTextFrame(i, ycenter, 2, size += 2, "", "", false);

WaitHard(1);

}

The horizontal unfolding happens first. In this stage, the frame is always two tiles high, and expands in width (here tracked in the size variable) by two tiles on each successive iteration.

The for loop governs the position of the left edge of the frame. It begins at xcenter, which is near the horizontal center of the screen, and decrements by one until left is reached. Once that happens, the horizontal unfolding stage is complete.

Within the loop, DrawTextFrame() is used to actually draw the frame at this position. i is the position of the frame’s left edge, and ycenter and 2 are the top/height values that keep the frame fixed and narrow in the vertical direction. size += 2 is an addition assignment operator, which adds two to the current frame width and returns the result of that addition. Since size is initialized to 1 prior to the loop, each iteration uses a width of 3, 5, 7, 9, and so on.

The top and bottom texts are empty strings, resulting in no additional text being rendered at this time. The false centering flag does not have any meaningful effect in this case.

Once the frame has been drawn, WaitHard() pauses execution for one game tick to govern the overall speed of the animation. The loop repeats until the frame reaches its final width, with each successive iteration completely covering (and overwriting) the area that was previously drawn.

size = 0;

for (i = ycenter; i > top + !(height & 1); i--) {

DrawTextFrame(left, i, size += 2, width, "", "", false);

WaitHard(1);

}

Now the frame unfolds vertically. The size variable tracks the current height of the frame, and i is the position of the top edge of the frame. The for loop begins with the top edge of the frame at ycenter, near the vertical center of the drawing area. The top position decrements by one tile – moving upwards on the screen – as long as a rather ugly comparison succeeds: i > top when height is odd, or i > top + 1 when height is even (that’s all that this bit-twiddling accomplishes).

The odd/even difference warrants another look: Back near the top of the function, ycenter was set to top plus half of height. Since the height-halving was performed as a bit shift on an integer, the value rounds down. This causes ycenter to be correct when height is odd, but a fractional tile too low on the screen whenever height is even. This would be enough of an accumulated error to push the bottom edge of the frame one tile position below the correct spot during the last iteration, resulting in a double-bottom border when the animation completes. Ending the animation loop one iteration early solves this edge case.

The remainder of the loop is largely similar to the horizontal stage previously discussed. Here the left position and width are held constant while top/height decrease/increase, respectively.

return DrawTextFrame(

left, top, height, width, top_text, bottom_text, true

);

}

Lastly, the final frame is drawn using the originally requested parameters. Here is also where top_text and bottom_text are shown for the first time. The return value works out to be the computed value of left plus one, indicating the first column where content could be drawn within the frame’s boundaries.

DrawTextLine()

The DrawTextLine() function draws a single line of text with the first character anchored at screen coordinates (x_origin, y_origin). A limited form of markup is supported to allow insertion of cartoon images, player/actor sprites, and text animation effects. Characters are drawn in left-to-right order. Newlines and text wrapping are not supported, and there are no guarantees about what will happen if the text runs off the edge of the screen.

Note:

While most of the font characters in the game have transparent areas and could be layered on top of arbitrary graphics, the digits 0–9 are completely opaque, drawn on a solid dark gray square. This difference is not normally visible inside text frames, since the frame’s fill color matches the color embedded in the font. If an attempt is made to draw a digit outside of this context, however, it will appear with a (possibly undesired) dark gray background.

The reason for this difference, by the way, is for the status bar. As the score/bombs/stars numbers change during gameplay, each new number can be guaranteed to properly overwrite any numbers that were already there. If the font digits had transparent areas, extra effort would be required to erase these areas prior to drawing the new digits, possibly causing flicker.

Markup is encoded by including a flag byte in the text content, followed by three or six ASCII digits in the range 0–9. The flag byte patterns, digit parsing, and behavior are as follows:

| Flag Format | Description |

|---|---|

\xFBnnn | Draw cartoon frame nnn at the current position. |

\xFCnnn | Wait nnn × WaitHard(3) before drawing each character, and play a typewriter sound effect for each non-space character. Can be “hurried” by holding the spacebar. |

\xFDnnn | Draw player sprite frame nnn at the current position. |

\xFEnnniii | Draw sprite type nnn, frame iii at the current position. |

As an example, to draw player sprite 14, the C string literal encoding would be "\xFD""014", or individual bytes FDh, 30h, 31h, 34h.

Note: In Turbo C, it is not possible to write the previous example in code as

"\xFD014"because the parser treats the entire sequence as a single hexadecimal number that doesn’t fit into achartype.

The drawing position is not adjusted to compensate for cartoons/sprites embedded in the text data. To prevent subsequent characters from overlapping on previously-drawn images, there must be an appropriate number of space characters in the text to clear anything that was previously drawn.

Flag type FCh draws the line in “typewriter” mode, where the text is drawn character-by-character with a typewriter sound effect played as each non-space character is drawn. Whenever text is being drawn in this mode, holding the spacebar will shorten (but not entirely eliminate) the delay and silence the sound effect – this “hurrying” behavior is always available during typewriter mode, even if this is not explicitly explained to the user in all cases.

void DrawTextLine(word x_origin, word y_origin, char *text)

{

register int x = 0;

register word delay = 0;

word delayleft = 0;

EGA_MODE_DEFAULT();

In this function, the variable x represents the horizontal offset, relative to x_origin, where the next character will be drawn. This is not necessarily the same as the read position in the text string due to the look-aheads required to parse markup flags.

Typewriter behavior is tracked in two variables: delay is the most recent delay value that has been read from the text stream, and delayleft is a decrementing counter that tracks how long a character’s delay has been running for. If the text is not being drawn in typewriter mode, both of these are zero. By default, typewriter mode is disabled.

The font, cartoon, and sprite tiles are all stored as masked tile graphics. The EGA hardware should be in its default state for this type of drawing. The EGA_MODE_DEFAULT() macro ensures the hardware is configured properly to handle this data.

while (text[x] != '\0') {

if (

text[x] == '\xFE' || text[x] == '\xFB' ||

text[x] == '\xFD' || text[x] == '\xFC'

) {

char lookahead[4];

word sequence1, sequence2;

lookahead[0] = text[x + 1];

lookahead[1] = text[x + 2];

lookahead[2] = text[x + 3];

lookahead[3] = '\0';

sequence1 = atoi(lookahead);

Overall, the function is a large while loop that continues as long as the current character read from text[x] is not null ('\0'). C strings use the null byte to indicate the end of each string in memory, and as long as a null byte hasn’t been encountered, there is more string data to process.

If the character read from text[x] is any of FEh, FBh, FDh, or FCh, we are looking at a markup flag and special handling needs to occur. Each instance of a markup flag is followed by at least three digits, which are read into a lookahead buffer. Since the buffer is itself a string, it too needs to be terminated with a null byte. With the lookahead buffer filled with the null-terminated three-digit markup data, atoi() can convert the digit string into a proper integer, which is stored in sequence1.

if (text[x] == '\xFD') {

DrawPlayer(

sequence1, x_origin + x, y_origin, DRAW_MODE_ABSOLUTE

);

text += 4;

The original flag byte in text[x] is considered again. If it matches FDh, a player sprite should be drawn at this position in the text stream. In this case, sequence1 represents the frame number of the player sprite that should be drawn.

The x variable holds the current horizontal drawing offset, and combining that with x_origin produces the screen tile position where this sprite should appear. Since text drawing only occurs on a single line at a time, y_origin is used unmodified. These parameters are passed to DrawPlayer() to perform the drawing. The DRAW_MODE_ABSOLUTE option is required to indicate that the passed X/Y coordinates are in screen space instead of game world space. If a sprite is comprised of multiple tiles, the passed X/Y coordinates represent the bottom left tile (the origin tile) of the sprite.

Once the player sprite is drawn, the text pointer is advanced by four bytes. This skips the flag byte and the three data bytes that followed it, and sets the read position to the next character following this markup construction.

Note:

This fundamentally messes with the indexing of the

textarray. Iftextwere to contain the value"Demonstrate",text[0]would be the characterD. After performingtext += 4, however,text[0]becomesn.Earlier it was hinted that the

xvariable is not necessarily the read index in thetextdata. This skipping behavior is the reason for that.

} else if (text[x] == '\xFB') {

DrawCartoon(sequence1, x_origin + x, y_origin);

text += 4;

This is largely the same as the previous block, handling the FBh code and drawing a cartoon image via DrawCartoon().

} else if (text[x] == '\xFC') {

text += 4;

delayleft = delay = atoi(lookahead);

This block handles the FCh code, resulting in a configuration of the typewriter feature. This is a three-digit code, and the skipping behavior on text works the same as the previous branches.

delay and delayleft are both set by re-parsing the lookahead buffer with atoi(). This is slightly wasteful, since this was already done earlier and could have been read from sequence1.

} else {

lookahead[0] = text[x + 4];

lookahead[1] = text[x + 5];

lookahead[2] = text[x + 6];

lookahead[3] = '\0';

sequence2 = atoi(lookahead);

DrawSprite(

sequence1, sequence2, x_origin + x, y_origin,

DRAW_MODE_ABSOLUTE

);

text += 7;

}

The final block at this level is a catch-all, which (through process of elimination) can only handle code FEh: drawing an actor sprite. This is the only markup code that uses six digits (encoding two separate three-digit numbers). The first number is the sprite type, which is already stored in sequence1. The sprite frame is stored in the second number, which must be read using another look-ahead into sequence2.

With both the sprite type and frame in hand, DrawSprite() performs the drawing. The calculation for X/Y and the inclusion of DRAW_MODE_ABSOLUTE works the same as in code FDh and friends above.

The text pointer address is advanced by seven here. This skips the flag byte, the three digit sprite type, and the three digit sprite frame.

continue;

} /* text[x] == one of FEh, FBh, FDh, or FCh */

This is the end of the if block that handles markup flags. If we parsed and handled a flag, there is nothing further to draw on this iteration of the outer loop and it should continue without performing any of the subsequent steps.

if (delay != 0 && lastScancode == SCANCODE_SPACE) {

WaitHard(1);

} else if (delayleft != 0) {

WaitHard(3);

delayleft--;

if (delayleft != 0) continue;

delayleft = delay;

if (text[x] != ' ') {

StartSound(SND_TEXT_TYPEWRITER);

}

}

Whenever execution reaches this point, there is a displayable font character at this position in text that needs to be drawn.

If typewriter mode is enabled, delay will have a nonzero value and this section of the code will generate delays between each character of text. If this is the case and lastScancode indicates that the spacebar (SCANCODE_SPACE) is being held, an abbreviated delay is generated with WaitHard(1) and nothing else is done here.

Otherwise, delayleft is considered. This is a counter that starts with the value of delay, decrements during each iteration of the outer loop, and permits drawing a character each time zero is reached. During each pass through this part of the code, WaitHard(3) produces a constant delay while the number of delayleft iterations controls the apparent speed of the text. Each instance of typewriter text in the original game uses a delay value of 3, resulting in a draw rate of approximately 15.5 characters per second.

If delayleft has not reached zero, the outer loop is continued without drawing anything. Otherwise, if the character being processed is not a space, StartSound() is called to begin the SND_TEXT_TYPEWRITER sound effect. Execution proceeds.

if (text[x] >= 'a') {

DrawSpriteTile(

fontTileData + FONT_LOWER_A + ((text[x] - 'a') * 40),

x_origin + x, y_origin

);

} else {

DrawSpriteTile(

fontTileData + FONT_UP_ARROW + ((text[x] - '\x18') * 40),

x_origin + x, y_origin

);

}

x++;

}

}

The remainder of the function draws a single text character and advances the horizontal drawing position.

The text content of the game is stored internally using standard ASCII encoding.2 The game font’s character set, however, uses a different encoding that is sort of like – but not actually – ASCII. This discontinuity requires some finesse to handle.

- ASCII codes 32–90 are mapped to font tiles 10–68. This covers capital letters, digits, and all of the symbols that the game font can display.

- ASCII codes 97–122 are mapped to font tiles 69–94. This range contains only lowercase letters.

- These symbols cannot be represented at all:

/[\]^_`{|}~and control characters. The only character in this list that does anything remotely reasonable is/, producing the symbol for the pound sterling (£). - The additional codes 18h, 19h, 1Bh, and 1Ch produce the symbols

↑,↓,←, and→respectively. This almost follows the standard, except the rightwards arrow is in the wrong place.

In this light, the first branch of the if is fairly straightforward. If the ASCII code of the current character is greater than or equal to that of 'a' (97), subtract 97 from the code to produce a value between 0 and 25. Combining this with the offset in FONT_LOWER_A produces the offset to the correct character tile in the font data. (The multiplication by 40 is due to the fact that each masked tile image is 40 bytes long.) The resulting byte offset is added to fontTileData to compute the memory address of the tile image that should be drawn to display the required character. This pointer, along with x_origin + x and y_origin, are passed into a DrawSpriteTile() call to display the character at the correct location on the screen.

The else branch handles all other cases. It works largely the same as the previous branch, except the constants are more obtuse. In the game font’s character set, the lowest-valued character with a meaningful definition is the upwards arrow, which is ASCII (technically, CP4373) value 18h. Subtracting that from the current character’s code produces the distance from FONT_UP_ARROW. Everything else works the same as it did in the previous branch.

Once the character has been drawn, x is advanced to set up another iteration of drawing, and the while loop continues until the end of the text is encountered.

DrawNumberFlushRight()

The DrawNumberFlushRight() function draws a numeric value with the rightmost (least significant) digit anchored at screen coordinates (x_origin, y_origin). value is interpreted as an unsigned long integer.

void DrawNumberFlushRight(word x_origin, word y_origin, dword value)

{

char text[16];

int x, length;

EGA_MODE_DEFAULT();

The text buffer is a 16-character array where the string representation of the number will be stored. The source value is an unsigned long integer which could create a string with anywhere from one to ten characters in it. Reserving an additional byte for the null terminator, this buffer is probably five bytes longer than it really needs to be.

x represents the horizontal draw position as the number is being constructed on the screen. The individual digits will be drawn left-to-right, but this value decrements in the process. It’s a bit more convoluted than it really needs to be. length is the length of the resulting string, in characters, used to determine how far the leftmost digit will be from x_origin.

The font tiles are stored as masked tile graphics. The EGA hardware should be in its default state for this type of drawing. The EGA_MODE_DEFAULT() macro ensures the hardware is configured properly to handle this data.

ultoa(value, text, 10);

length = strlen(text);

ultoa() converts the unsigned long integer in value into a string, storing the result in text. The number 10 is the radix, telling the function that it should display the number using the base ten “decimal” numbering system. length is computed by calling strlen() on the text value.

for (x = length - 1; x >= 0; x--) {

DrawSpriteTile(

fontTileData + FONT_0 + ((text[length - x - 1] - '0') * 40),

x_origin - x, y_origin

);

}

}

Here the individual digits are drawn in a for loop, running in left to right order. The calculations involving x, x_origin, and length are needlessly complex for what they’re actually doing – the rightmost digit ends up at x_origin, while the leftmost digit appears at x_origin - length + 1. The horizontal math could be greatly simplified by either drawing right to left, or by incrementing x instead of decrementing it.

Each character of text is an ASCII digit in the range 30h–39h. The ASCII code value is subtracted by '0' (30h) to produce a numeric value between 0 and 9. This is multiplied by 40 and added to FONT_0 to calculate a byte offset into the font tile image data. Finally, this is combined with the base fontTileData pointer, giving the memory address where the required tile image data for this character resides. This is passed to DrawSpriteTile() along with the appropriate X/Y screen position, and a font digit is drawn.

The for loop continues until the entire number has been drawn, then this function returns.

ReadAndEchoText()

The ReadAndEchoText() function presents a wait spinner near (x_origin, y_origin) that accepts at most max_length characters of keyboard input. The typed characters are echoed to the screen and stored in the memory pointed to by dest, which should be large enough to hold max_length + 1 bytes of data. If the user presses the Esc key, input will be aborted. The Enter key accepts the input.

Note: This function draws everything one tile to the right of the screen column specified by

x_origin.

The user cannot arbitrarily move the text insertion cursor around to edit text. New characters are always appended to the end of the text, and any deletions (using the Backspace key) remove characters from the end of the text as well.

void ReadAndEchoText(

word x_origin, word y_origin, char *dest, word max_length

) {

int pos = 0;

for (;;) {

byte scancode = WaitSpinner(x_origin + pos + 1, y_origin);

The only internal state maintained by this function is the pos variable, which tracks the number of input characters that have been filled so far. This also influences the position of the wait spinner and freshly-drawn characters.

The bulk of this function is structured as an infinite for loop. During each iteration, a call to WaitSpinner() blocks until a character is typed on the keyboard. The wait spinner is placed horizontally at x_origin plus pos plus one, for reasons that are only apparent to the original author. This causes the initial position of the wait spinner, and everything drawn relative to it, to appear one tile position to the right of where x_origin would suggest. Vertically, all drawing occurs in the y_origin screen row.

Once a character has been typed, its keyboard scancode is returned in scancode and execution moves on. The wait spinner erases itself before returning, so there is no need to worry about cleaning up the drawing area.

if (scancode == SCANCODE_ENTER) {

*(dest + pos) = '\0';

return;

If the scancode that was just typed is the Enter key (SCANCODE_ENTER), the user has completed their input and wishes to use the result. Write a null terminator byte to the position pos bytes into the dest memory, then return from this function.

} else if (scancode == SCANCODE_ESC) {

*dest = '\0';

return;

Otherwise, if the scancode is the Esc key (SCANCODE_ESC), the user wishes to cancel the input. Since the dest memory may or may not have partial data stored in it, overwrite the first byte with a null terminator, effectively turning dest into a zero-length string. Any data that may exist past the terminator should automatically be ignored by any well-behaved string functions. return once this is done.

} else if (scancode == SCANCODE_BACKSPACE) {

if (pos > 0) pos--;

In the event that the user made a text entry error, the Backspace key (SCANCODE_BACKSPACE) will erase the most recently-typed character. This is accomplished by simply decrementing the pos variable – any subsequent character typed (including the null terminator in the case of the Enter key) will replace the erroneous character in the dest memory.

The character on the screen is not actually erased here. When the outer for loop executes again, the wait spinner will be positioned on top of the erroneous character, replacing it.

In the event pos is zero, the cursor is already at the beginning of the text and nothing more can be deleted. In that case, do nothing.

} else if (pos < max_length) {

if (

(scancode >= SCANCODE_1 && scancode <= SCANCODE_EQUAL) ||

(scancode >= SCANCODE_Q && scancode <= SCANCODE_P) ||

(scancode >= SCANCODE_A && scancode <= SCANCODE_APOSTROPHE) ||

(scancode >= SCANCODE_Z && scancode <= SCANCODE_SLASH)

) {

*(dest + pos++) = keyNames[scancode][0];

DrawScancodeCharacter(x_origin + pos, y_origin, scancode);

This is the typical case: If the max_length has not yet been reached, check the scancode to determine if it represents a displayable character. The scancode arrangement mirrors the standard IBM U.S. English keyboard layout:

- Row 1: 12 keys starting with 1 and ending with =.

- Row 2: 10 keys starting with Q and ending with P.

- Row 3: 11 keys starting with A and ending with ’.

- Row 4: 10 keys starting with Z and ending with /.

If the scancode is in the printable range, use the first character of that scancode’s entry in the keyNames[] array to find the correct ASCII character that represents the key. It is not possible to use the Shift key to change the characters typed. All letters are capital, and (almost) all number/symbol keys are drawn in their unshifted state. The exceptions are the apostrophe and slash keys, which display as " and ? respectively.

The resulting character byte is written to the current position in the dest memory and the pos variable is incremented.

The scancode and X/Y position of the new character are passed to DrawScancodeCharacter(), which draws the typed character onto the screen.

} else if (scancode == SCANCODE_SPACE) {

*(dest + pos++) = ' ';

}

}

}

}

The only other special case to handle is the spacebar (SCANCODE_SPACE). The writing to dest memory works the same as in the previous branch, but here there is no need to explicitly draw any character tiles. The erasing behavior of WaitSpinner() during each iteration of the outer for loop adequately produces blank spaces where they need to appear.

For all unrecognized scancode values, no action is taken. In all cases, the outer for loop repeats indefinitely until either Enter or Esc is pressed.

DrawScancodeCharacter()

The DrawScancodeCharacter() function draws a single-character representation of scancode at screen tile position (x, y).

The technique used by this function is to simply draw the first character from keyNames[] for the provided scancode. This works well for letter, number, and symbol keys, but it does not work well for other keys. For instance, the keyNames[] element for the Backspace key is BKSP, which would be rendered by this function as B. Even practical keys like Spacebar would render as S here.

This function should ideally be called from something like ReadAndEchoText() that ensures only appropriate characters are passed.

void DrawScancodeCharacter(word x, word y, byte scancode)

{

char text[2];

text[0] = keyNames[scancode][0];

text[1] = '\0';

DrawTextLine(x, y, text);

}

text is a two-character buffer that only contains enough space for a single display character and a null terminator byte. Its content is immediately filled with the first character of the keyNames[scancode] array element. This buffer is passed to DrawTextLine() along with the x and y screen positions, and this scancode’s text representation is drawn.

WaitSpinner()

The WaitSpinner() function draws a rotating green icon at tile position (x, y) on the screen, blocking until a key is pressed. Once that occurs, the scancode of the pressed key is returned.

The wait spinner is used to indicate that the game is waiting for a user to press a key. In certain cases (for example, in the high score table) the wait spinner also serves as a cursor for text entry.

byte WaitSpinner(word x, word y)

{

byte scancode;

While this function is executing, external interrupts occur asynchronously, sometimes invoking the KeyboardInterruptService() function in response to keyboard events. The keyboard interrupt service updates the lastScancode and isKeyDown[] variables to reflect the keyboard state. Generally the local scancode variable will mirror the value held in the global lastScancode variable, and the duplication here really only serves to obscure that fact.

do {

scancode = StepWaitSpinner(x, y);

} while ((scancode & 0x80) == 0);

StepWaitSpinner() is called in a do…while loop, which continually draws each successive step of the wait spinner’s animation at (x, y). StepWaitSpinner() returns immediately after each call, returning the most recently-seen keyboard scancode which is saved into the scancode variable.

When this function was first entered, there was a slight chance that the user was still holding down the key that brought execution to this point. In that case, the most recently seen scancode would be a “make” code in the range 1–7Fh. (See the page on keyboard functions for more information about make/break states and scancodes in general.)

This first loop serves to capture that case. As long as the most recent scancode byte represents a make code (with the most significant bit unset), repeat. Once the held key is released, a break code will arrive with the most significant bit set and execution will move on.

do {

scancode = StepWaitSpinner(x, y);

} while ((scancode & 0x80) != 0);

This is identical to the previous loop, except the termination condition is inverted. This is waiting until the next make code arrives. Once the user presses a key, this loop will terminate.

The PS/2 makes it weird, of course.

The implementation here seems simple enough to be bulletproof: block until a key release message arrives, then block until a subsequent key press message is seen. There’s no obvious way to blaze through wait spinner calls by holding down a key; there must be a deliberate release followed by a press.

But where there’s a will there’s a way. On the original 84-key PC/AT keyboard, pressing and holding a key – say Num 8 / ↑ – repeatedly sends that key’s “make” code byte (48h) as long as the key is held.

0x48 & 0x80 == 0, so the first loop will block for as long as the key is down.On the PS/2 keyboard, IBM added a standalone ↑ key that uses the same 48h scancode byte, but prefixed with an E0h flag byte to allow the software to differentiate the keys if desired. While this key is held, the keyboard repeatedly sends two bytes (E0h 48h E0h 48h…) and the E0h unintentionally terminates the first loop. Then 48h terminates the second loop, and we’ve successfully bypassed the release-and-press requirement.

The effects of this can be seen clearly in some menus: Ordering Information, Story, and Test Sound are a few clear examples. Holding one of the standalone arrow keys down will rapidly move through the screens/options, while holding the same arrow key on the numeric keypad will not. This certain-key-holding behavior can also occur during the game, causing hint dialogs to disappear as soon as their built-in delays expire.

scancode = lastScancode;

isKeyDown[scancode] = false;

Some scancode manipulation occurs. scancode is refreshed with the latest value from lastScancode. This should generally not change anything since scancode was being continually refreshed in the loop that just ended, but there is a nonzero chance that this could set scancode to something different than what was seen inside the loop – including a break code – if a keyboard interrupt slips in. It would be an improvement to remove this assignment entirely.

The isKeyDown[] array is manipulated to clear the “key is pressed” state of the key the user pressed. The wait spinner, in essence, “consumes” this keypress and removes it from consideration by any other part of the program.

EraseWaitSpinner(x, y);

return scancode & ~0x80;

}

Before the function returns, EraseWaitSpinner() is called to erase the space the wait spinner was occupying. The return value is scancode with the most significant bit forced off. This would transform any errant break codes into their corresponding make codes, but this should generally not happen.

EraseWaitSpinner()

The EraseWaitSpinner() function erases an area previously occupied by a wait spinner by drawing a tile of solid dark gray at screen tile position (x, y). This is appropriate inside of text frames that have dark gray backgrounds, but may not be appropriate on backgrounds of different colors.

void EraseWaitSpinner(word x, word y)

{

EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE();

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(TILE_DARK_GRAY, x, y);

}

The wait spinner graphics are solid tiles, which are stored in the EGA’s onboard memory. For the drawing functions to properly copy this data from one location in video memory to another, the EGA hardware must be in placed in latched write mode with the EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE() macro.

The essence of this function is a call to the DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY() macro, drawing one tile of TILE_DARK_GRAY at screen position (x, y).

StepWaitSpinner()

The StepWaitSpinner() function draws one frame of the wait spinner, immediately returning the most recent scancode seen by the keyboard hardware (even if that scancode is stale). This is a lower-level function to support WaitSpinner().

The wait spinner itself has a solid dark gray background, and each call to this function completely erases the contents that were previously in that position on the screen.

byte StepWaitSpinner(word x, word y)

{

static word frameoff = 0;

byte scancode = SCANCODE_NULL;

frameoff tracks the current state of the wait spinner animation. Since it is declared static, it retains its value between calls. When subsequent wait spinners appear, frameoff might not be zero and the animation could start in a different position.

scancode is a temporary storage area for the most recently seen keyboard scancode, and does not really do anything important in this function. It is explicitly zeroed to start.

EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE();

The wait spinner graphics are solid tiles, which are stored in the EGA’s onboard memory. For the drawing functions to properly copy this data from one location in video memory to another, the EGA hardware must be in placed in latched write mode with the EGA_MODE_LATCHED_WRITE() macro.

if (gameTickCount > 5) {

frameoff += 8;

gameTickCount = 0;

}

if (frameoff == 32) frameoff = 0;

This portion of the code governs the speed and progression of the wait spinner animation. The gameTickCount counter is constantly being incremented as timer interrupts are handled by TimerInterruptService(). Once the counter increments above 5, frameoff is incremented by 8 and gameTickCount is reset to zero.

gameTickCount increments at a rate of 140 Hz, so this if block body runs about 23.3 times per second. The frameoff increment by 8 advances by one solid tile in EGA address space. Since the wait spinner tiles are stored sequentially in memory, this scheme works wonderfully.

Once frameoff reaches 32, all four wait spinner tiles have been encountered and the offset is reset to 0. This loops the animation over successive calls.

DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY(TILE_WAIT_SPINNER_1 + frameoff, x, y);

The actual drawing occurs here, during every call, even if frameoff has not changed. TILE_WAIT_SPINNER_1 is the EGA memory address of the first tile in the wait spinner animation, and frameoff adds 0, 8, 16, or 24 to that base address to access the remaining tiles. The DRAW_SOLID_TILE_XY() macro draws that tile onto the screen at tile position (x, y).

scancode = lastScancode;

return scancode;

}

Finally, the value held in lastScancode is copied into scancode, then returned. All this is fairly unnecessary, since the caller has direct access to lastScancode if it wants.

Be nice.

There was probably a time when this function did more direct operations with keyboard state, similar to the structure of

WaitForAnyKey(). In that mindset, it makes a bit more sense whyscancodeis explicitly zeroed at the beginning of the function, and why it gets returned as it does.At the end of the day, done projects are better than perfect projects.